Scene Change

hen The Media TheatRe in Media, Pa., canceled its live performances, musical director Ben Kapilow ’13 found himself missing his busy schedule — and his creative outlet.

After almost a month of rehearsals, he was devastated when the musical Baby was forced to close before the public had a chance to see it.

“It was very sad,” says Kapilow. “Everybody put in a lot of work. We had three preview performances, which went great. On the third and final one, the executive director of the theater told the cast and crew and musicians it had to shut down.”

The small but iconic theater, constructed in 1927 as a vaudeville house, was converted into a space for the performing arts in 1994 after a renovation brought the English Renaissance-style building back to its glory.

Kapilow, 30, has stopped conducting and composing music there, but still goes into the acclaimed regional theater to teach lessons and small-group classes. He has redirected his creative energy into helping his young students write their own music and create virtual concerts filled with animated graphics, photos, and other creative flourishes.

For the composer, 2020 has been a test of adaptability.

“A lot of the ways that I was trying to be creative prior are not possible now,” he says. “Teaching used to be one of the things I did on the side. Now, with 55 private students, I have plunged full on into teaching.”

As a successful composer who received a B.A. in music and psychology from Swarthmore and a master’s in composition from the Peabody Conservatory, Kapilow is imparting his knowledge to his songwriting and composition students. He wrote the score for three children’s musicals for the Media Theatre, including Peter Pan and Wendy, which won the Broadway World “Best of Philadelphia Theatre” award for Best New Work and was also produced at A Contemporary Theatre of Connecticut in 2018.

To mitigate the COVID-19 risk, he did his annual student recital virtually, compiling student videos, editing them, and live-streaming the recital on YouTube. He opened one by saying: “Although I miss the days of teaching in person and being able to scream rhythm syllables super-loud to the kids without being hindered by masks and the decibel limits of microphones, teaching during the pandemic has been great. These videos will show kids can be creative and still have fun during the pandemic.”

A student named Josephine shows a music video of her song “Summer,” juxtaposing photos of herself with bright, beachy graphics. Another student wrote a political rock song about fighting injustice. “It’s fun to work with a student on something that is not a musical, in a completely different universe than something I would write,” Kapilow says.

The pandemic continues to inspire other student scores. “The arts are one way for them to try to make sense of all the craziness going on. … This is a lot to take in and make sense of,” Kapilow says. “Writing lyrics and writing music is one way to use the arts to try to channel all their different emotions.”

Kapilow is grateful for the virtual recitals, and plans to continue them even after the pandemic ends. But while he enjoys teaching remotely, he misses the camaraderie of his pre-pandemic life.

“Sometimes I would accompany for auditions and meet hundreds of actors, or I would lead a small orchestra of professional instrumentalists through a music rehearsal, or I would play piano and conduct in front of a 300-person audience,” he says. “Today, due to the pandemic, all of that is gone. As rewarding as teaching is, I do greatly miss the social thrills of professional music directing.”

Eliza Blue ’00 (aka Beth Bonacci) is a transplanted city girl who herds sheep and tends to grass-fed cows on a ranch in South Dakota, more than a mile from her next-door neighbors. The closest town is the high-plains hamlet of Bison, population 331.

The singer-songwriter never expected to call this home, but nine years in, it’s no longer a stop along the way. Living close to the land, she’s discovered a connection with nature and the wide-open sky that inspires her lyrically.

This summer, during the darkness of the pandemic and the rancor of political divisions, the words poured out of her like never before. The Black Hills and open spaces conveyed a message of inner hope.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, governments, businesses, and people around the globe have radically altered the way they interact with and inhabit the world. For some, the rhythm of everyday life has adapted to this “new normal.”

In the world of the visual arts, however, this new landscape has prompted institutions to adopt a number of new practices and strategies, some more problematic than others.

Most institutions are still reeling from the financial blow dealt to them last March and April. Mass layoffs and furloughs have left many entry-level and part-time employees without work. To offset this loss, museums and galleries have been eager to hire interns, a more cost-effective solution than reinstating laid-off employees on a full- or part-time salary. Entry-level opportunities in art had already paid poorly, if at all. Now, they are almost exclusively limited to those who can afford to eschew full-time pay to gain a foothold in the art world.

The financial toll of the pandemic is also affecting museums’ permanent collections. Faced with huge losses of income due to the spring shutdown, some institutions have turned to deaccessioning artworks from their collections in order to stay afloat.

For others, the decision to jettison untaxed, valuable works of art from an ostensibly “permanent” collection in the name of fundraising appeared callous and unethical. However, some have argued that retaining pieces with astronomical prices may not be as valuable as the myriad programs that could be funded through their sale.

Despite the universal belt-tightening faced by museums and other art spaces, the pandemic has also led to new instances of community-building and collaboration. The “streaming-age” initiative, led by the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid, is a digital platform for artworks and projects from around the globe to address the pandemic, education, climate justice, and other issues of social justice.

Institutions in India, Chile, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and more have participated in the project. By fostering international dialogue and exchange, streaming-age demonstrates the potential of new initiatives to build community and address the important issues of our day.

MAX Gruber ’20 is a gallery assistant at Helena Anrather gallery and Tina Kim Gallery in New York City. He earned a B.A. in art history, history, and Spanish.

Across the plains,

the wide world open

the grasses wave,

the sod’s not broken.

Weaving wire round

all I’ve stolen,

I long for words

that can’t be spoken.

I search the fields

for scraps and tatters

the sparrow’s flown

but left her feathers.

Against the loom of love

I’ve shattered everything

that I thought mattered.

Let there be light.

“It wasn’t my mission to write songs that unite us,” says Blue. “The songs just come out the way they come out. But that is what they mostly have been — finding the comfort we can bring to ourselves and to each other.”

For Blue, songwriting is not a daily practice but a burst of inspiration. She writes whenever she can catch a few minutes, such as in the bathroom when her two young children are taking baths, or after they go to sleep.

Her English literature degree from Swarthmore helped her to craft lyrics. Her extracurricular work in theater refined her stage presence. “I learned about connecting to an audience as well as how to tap into my intuition as a performer,” she says. “The emphasis in most of the productions was finding authenticity in performance, and I continue to bring that to my work as a singer and a storyteller.”

In the 17 years she spent on the road touring, Blue sang and played her guitar, banjo, and violin in venues ranging from ramshackle front porches to big concert halls. She stopped touring before the pandemic hit. It was too hard with two kids in tow, and it became increasingly difficult to make a living as a musician with Spotify and other streaming services eating into album sales.

She and her husband now support themselves mostly through ranching. She also wrote a book called Accidental Rancher — the story of how her break from touring unexpectedly turned into a whole new lifestyle.

In some ways, Blue’s background as a folk singer and songwriter has prepared her for the uncertainty brought about by the pandemic.

“I feel like every artist I know spends their entire career braced for everything to fall apart. It’s like, ‘When is the next project? Is it even gonna happen? Am I going to get any money? Am I gonna pay my rent?’”

But letting go of music was never an option.

Blue and other musicians received funding from an NPR affiliate to produce Wish You Were Here, a variety show held in noteworthy but out-of-the-way small towns. The program will air in January on South Dakota Public Broadcasting.

“We did intros about the places and what makes them special,” she says. “It’s meant to be a postcard from that place. While we still can’t be together, how can we create shared experiences? I feel that music is just something we need. Music is an essential part of being human.”

In Kim Foote ’00’s one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, N.Y., almost every corner is filled with books. The tall cherry bookcase in her living room contains fiction by Octavia Butler, Ayi Kwei Armah, and other favorite authors.

Then there is what she calls “my own shelf,” where she keeps copies of the magazines and books where her short stories and essays have been published. There is a designated empty space on that shelf — a placeholder for her future books.

“There is a burning desire in me to tell a story,” she says. “The way I write, I see movies in my head, and I have to translate them into words.”

Foote writes literary fiction and nonfiction under the name Kim Coleman Foote. Her work has been published in prestigious journals such as Prairie Schooner and The Missouri Review. She has been awarded writing fellowships from MacDowell, the Center for Fiction, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Illinois Arts Council, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

For her, the written word is a way to process some of the dark and uncomfortable realities of life and to explore themes such as the transatlantic slave trade, racism, and trauma.

“I’m deeply grateful for my Swarthmore education,” she says. “It honed my critical thinking and research skills, which enabled me to contextualize marginalized histories.”

A night owl, she works in spurts, sitting at a desk in her bedroom, which is spacious by New York standards. She writes short stories that fictionalize her family’s experiences during the Great Migration, traveling from Alabama and Florida, where her great-grandparents were sharecroppers, to New Jersey, where she grew up.

Their stories of dashed hopes and trauma are told from the viewpoints of various family members. She’s also been revising her novel, Salt Water Sister, which tells the stories of women during the transatlantic slave trade, alternating between 18th-century West Africa and the year 1999 in the United States and Ghana. Her novel was inspired by the college semester she spent in Ghana, where she returned to conduct follow-up research as a Fulbright fellow from 2002 to 2003.

The harsh realities of the pandemic have made it harder to immerse herself in that fictional world. “My writing takes me to such dark and heavy subject matter,” she says. “I am already in my head a lot.”

Foote, who works remotely as assistant director of a study-abroad office at New York University, says social isolation has been hard.

“Despite my many writing accomplishments, I am still single, and it hurts not to have a partner to share with,” she says. “Living alone through the pandemic has only intensified this.”

Regular walks in nearby Prospect Park, and a writing community through her Zoom critique group, give her solace.

Foote has experienced the ups and downs of the fickle publishing world. She previously had an agent for Salt Water Sister who ultimately told Foote that the subject was too dark. Others have suggested that she revise it in ways not true to her vision.

One editor told her, “The writing is really good, but I can’t work with it because it is set in Africa and it’s historical. Why don’t you switch it to the United States?”

“Seriously?” Foote thought.

But she received good news during the pandemic: She won a prestigious Yaddo writing residency, a retreat for artists in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. It’s been delayed this year, but even so, it was gratifying to be recognized.

One of her short stories, written in Black dialect, was published this fall in the literary magazine Prairie Schooner, and an agent who admired it reached out to her. “You have a fan here,” he wrote. He wanted to see more of her short-story collection inspired by her family. She sent him her work and crossed her fingers, hoping to fill in the bookshelf space saved for her own writing.

Hannah Schutzengel ’11 finds meaning through the art she makes with her hands — touching, folding, and refolding pieces of fabric.

It’s an odd juxtaposition, relying on touch to create multimedia pieces at a time when people shrink from each other to avoid contracting a deadly disease.

Like Foote, she lives in a New York City that has changed dramatically since March. Art openings were cancelled, including a show featuring her work at The Textile Arts Center that moved online.

During the early months of the pandemic, Schutzengel worked from home with no access to her studio supplies. Instead of manipulating fabric, she has created elaborate pencil drawings of folded garments inspired by gothic and Medieval sculptures. “It’s a very slow, deliberative process, which felt good during the quarantine.”

Like Foote, she juggles the life of an artist with steady paying jobs. She works part-time at an art gallery and as an advisor in the art department at Hunter College, where she received her MFA after studying art at Swarthmore.

Schutzengel’s art keeps changing. At Swarthmore, she created oil paintings of carefully constructed still lifes. Now, her mixed media paintings rearrange fabrics, threads, paper, and plastic fragments to form six-inch squares which she casts in resin. “My work uses slow, subtle gestures to create experiences of quiet, everyday emotion: casual warmth and comfort, playfulness, ease. Each action transforms materials to create a feeling of care, attention, and thoughtfulness.

“All of these gestures feel very different now,” she adds. “I am thinking of surface and gesture at a time when we have all become hypervigilant about everything, every person we touch, every place we go.

“It gives a different valence to my work.”

As Pablo Picasso famously said: “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”

Arguably, the most prolific and perhaps creative artists in the world are children. What can we learn from them about how to engage with art in the challenging context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Children use art to express themselves and to communicate with others. Creating art can also help them process and explore their feelings and experiences. Throughout early childhood, making art is a joyous and significant form of play. But as children get older, they are given less time, space, and freedom for artistic expression.

Too often, children and their cultural productions are ignored or disregarded. But engaging with children’s art has the potential to offer insight into the circumstances, consequences, and urgencies of this crisis. As experts on themselves, children are best positioned to explain and elaborate upon the meaning of the work they create.

Parents, teachers, and museum practitioners are among those who most often facilitate children’s art-making. Since the pandemic began, art galleries around the world have reported dramatic increases in the number of online visitors. Children, and those caring for them, are one of the main target audiences. A proliferation of museum programming and educational materials have helped fill in the gaps of virtual learning as many schools have chosen to go online.

While enriching and valuable, the vast majority of this content consists of activities and resources for children, designed by adults. In this conventional top-down approach, adults hold most of the authority and set the terms of engagement. It misses an opportunity to explore content and programming by and with children, who may have unique contributions to make, drawing from their own expertise, capabilities, and capacity for creativity and innovation.

In this emerging field of practice I call critical children’s museology, children and youth have opportunities to share their own curations and artistic work, organize their own programming, and, in rare cases, contribute to the permanent collections of museums such as the International Museum of Children’s Art in Oslo and the Foundling Museum in London.

This child-centered approach stands to offer a more critical component to contemporary museological practice in at least two senses of the word: critical, as in grounded in critique of the adult-dominated status quo, but also critical, as in crucial to engaging with children as valued social actors and knowledge-bearers.

MONICA EILEEN Patterson ’97 is assistant director, curatorial studies, at Carleton University’s Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art, and Culture; and associate professor at Carleton’s Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies.

For math and honors studio art major and ballet dancer Emmeline Wolf ’22, the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown last spring meant the loss of the arts activities and dance rehearsals that had anchored her hectic weeks at school, as well as the Ireland painting residency and Bard College fashion- marketing program she was to complete during the summer. But she knew that for professional artists, the lockdown had more serious consequences: the loss of their livelihoods.

To address all of these losses, Wolf created fashion brand Le Corps/The Body, an original line of printed and upcycled clothing. The brand donates 25% of each sale to the Foundation for Contemporary Arts Emergency Grants COVID-19 Fund, and since creating the brand in June, Wolf has met her goal of donating $2,000 relief grant to the fund.

Wolf says an exhibit of Michelangelo’s drawings at the Getty in Los Angeles inspired her to put paintings of figures on each item. She used an L.A.-based sustainable-clothing agency to create printed items and dug through closets of family and friends to find vintage clothing she could paint.

What Wolf says she enjoyed even more than creating these items — and what surprised her about the process — was creating a community during an isolating lockdown. She showcased the work of fellow artists on the brand’s Facebook and Instagram pages and asked a variety of people around her to model her clothing: kid cousin, brother, grandmother, friends, friends’ parents, even a figure made of sticks.

Swarthmore students feature prominently among these collaborators, including VERO, the music act of Veronica Yabloko ’22, who performed live on Le Corps’ Facebook and Instagram pages. Wolf also raised $125 for the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, held remotely in 2020, in a collaboration with fashion blogger Cassandra Stone ’20.

“When I started, obviously I was feeling a lack of funding in the arts and a loss of community,” Wolf says. “But I don’t think I realized how important it was for me to rebuild that community and even create new ones.”

As she took remote classes from a Philadelphia apartment in the fall, Wolf continued to maintain the business and look for more opportunities to pursue a career in fashion marketing.

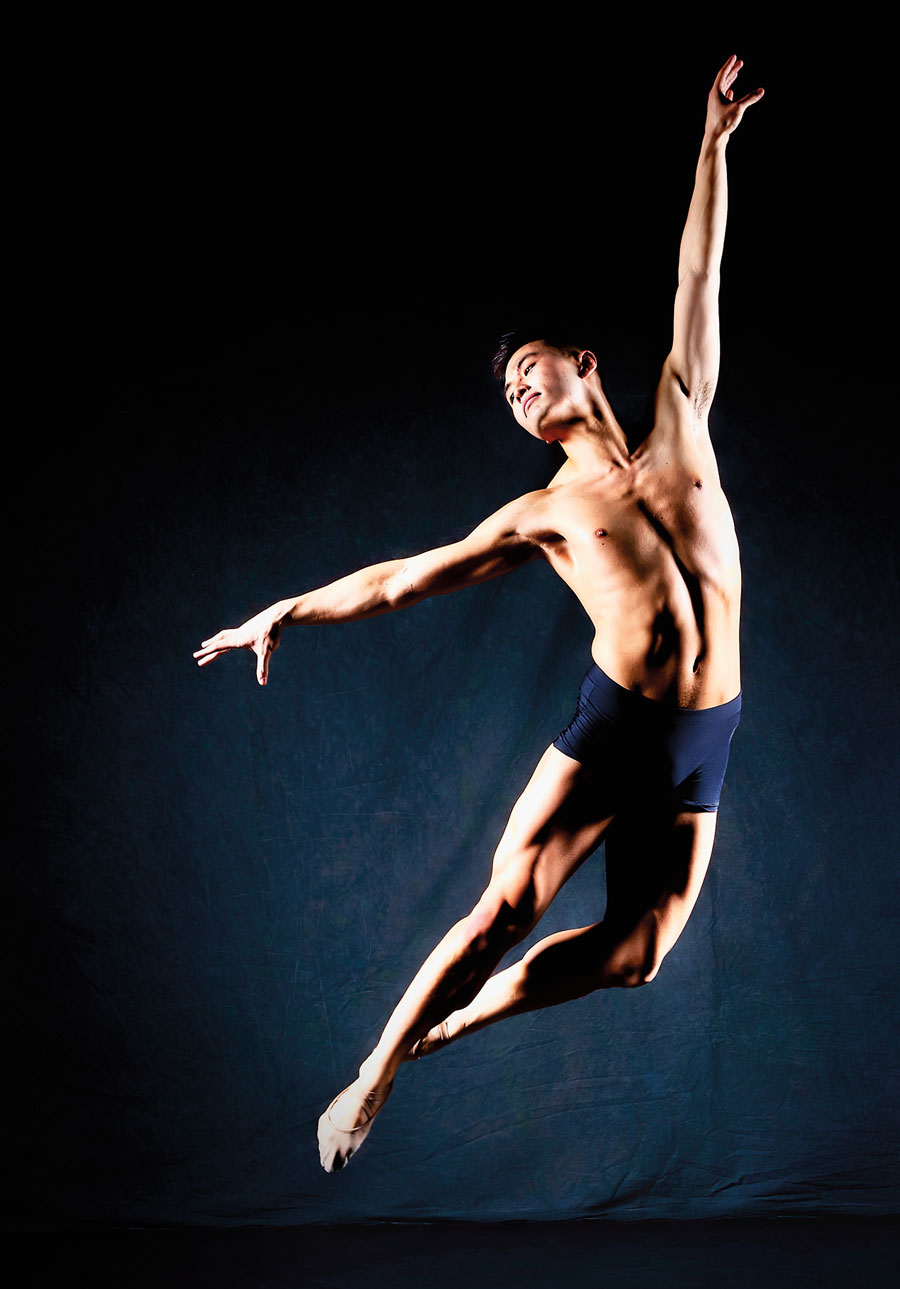

One August evening in a Cleveland parking lot, Daniel Cho ’15 got a sweet reminder of pre-pandemic life.

Cho swung his arms and stomped his feet, his body undulating to the African drumbeat. It was electric, the energy flowing between the audience, peering through their car windows, and the Verb Ballets company dancers on the makeshift stage.

Even behind his mask, Cho felt free as he performed in Surge.Capacity.Force, a modern-dance piece choreographed by Tommie Waheed-Evans and inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement. The choreography and soundtrack communicate the sense of disenfranchisement of minorities and immigrants, as well as the idea that people of all backgrounds have a rightful place in America. The political message resonated with Cho amid the social and political unrest of the times and as an Asian American artist in the overwhelmingly white world of dance.

Each dancer had a solo, and Cho ended his by calling out to the audience: “I belong here. What about my family? I’m a citizen, too. I have rights as well.”

The drive-in dance performance was emotional, an adrenaline rush of putting on a live show for the first time in months. The audience cheered wildly, as thirsty to watch live dance as the dancers were to get back to the stage.

“Something like that had not been done before, renting out a parking lot and building a stage,” Cho says.

For artists like Cho, the pandemic has been a particularly stressful time.

As live performances have dried up, many arts organizations have laid off performers, while others have gone under altogether. Yet these are the times when artists and audiences alike are most in need of the arts.

And so the urge to create and connect bubbles up in new ways — like a drive-in dance performance.

“It was really emotional,” Cho says. “It was nice to feel the reciprocity of the audience again.”

Being a professional dancer is hard enough without a pandemic. Injuries are an occupational hazard — Cho herniated a disc in his lower back last year — and jobs are scarce. The lack of support for the arts during the global health crisis has been disheartening to him: Consider the contrast between the New York City Ballet laying off some of the best dancers in the world versus the NBA renting out parts of Disney World to play basketball.

“It was depressing,” says Cho, “to see how few resources were given to artists.”

He entered Swarthmore with plans to be a vocalist, perhaps an opera singer, but then he took his second college dance class and knew that dance was what he would do — even with the late start. Since his sophomore year, the 27-year-old’s life has revolved around dance.

“In retrospect, it was kind of crazy,” he says. The small and supportive dance program at Swarthmore helped nurture his dreams, and after graduation, he landed a job at Verb Ballets. The company was small enough to resume in-person practices in June and send out recitals virtually. But wearing a mask has been difficult — gasping through six to eight hours a day of aerobic exercise, the sweat building inside, facial expressions hidden from view.

Still, going to the studio is cathartic. “For me, the joy comes from going in every day and just trying to improve yourself more, the daily habit of working on your craft,” he says. “It’s like, ‘How can I try this? How can I do this differently today?’ I feel like that’s a great metaphor for life.”