think

Again

Think

Again

athryn Riley ’10 is an analytical chemist, a record-holder and assistant coach for Swarthmore softball, an advocate for diversity and inclusion. But just as important, she’s a planner.

When the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the spring, Riley struggled to quickly shift to instruction online. Having a summer to prepare for the new academic year helped.

Still, uncertainty abounded.

“I’ve learned a lot about myself in terms of my ability to think on the fly,” says Riley, an assistant professor of analytical chemistry. “You have to stay on top of all of the little details to make a course that’s going to serve 140 students run smoothly, but you also need to see the bigger picture of what’s going on in the world.”

Across the College, faculty devised strategies to bring the key elements of traditional instruction to online and hybrid class formats. A major part of this challenge was maximizing student engagement through technology, and the comprehensive efforts of Information Technology Services staff were indispensable to this effort.

From restructuring courses to succeed online to connecting with students and experts around the world in real time, Swarthmore has stretched to maintain a human connection for learning in the pandemic.

“Students are super engaged in class, asking great questions, working well together in breakout rooms on Zoom,” says Riley. “Things are obviously not ideal, but we’ve been able to capture quite a bit of what makes our courses special at Swarthmore.”

And some aspects of teaching feel unchanged. Professor of Religion Mark Wallace was already seizing every opportunity to teach outside, pre-COVID-19. But while the shift to virtual was daunting, Wallace is starting to see some silver linings.

“I’m actually much happier about the learning dynamic, the energy of students, and the likelihood of getting into complicated and nuanced material than I initially thought was possible,” he says.

The pandemic spurred a career change of sorts for Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach.

“I’ve transformed from a professor to a YouTuber,” he says, recording videos that he uploads as lecture material. Everbach says he once spent four hours to produce a 20-minute product with some imperfections.

“For decades, I’ve trained as a live performer, not a studio musician,” he says, “and it has been hard to transfer those skills playing to no one in the house.”

Such adaptability has been key. In an ordinary summer, the Educational Studies faculty would have coordinated with local schools to arrange fieldwork; for Associate Professor Elaine Allard ’01’s course Educating Emergent Bilinguals, students would typically spend three hours a week with bilingual students in Philadelphia schools serving predominantly immigrant communities.

“But this semester, they’re doing fieldwork by mentoring small groups of seniors at our partner school, via Zoom, and by viewing and discussing classroom video,” says Allard.

Also emphasizing a combination of video and small-group interactions was Richter Professor of Political Science Carol Nackenoff, whose students streamed films and documentaries that they then discussed in online breakout rooms.

Some faculty have actually come to view elements of virtual instruction as a more efficient way to share information than on chalkboards or projects in class, says Wallace, who uses a stylus to write ancient Greek on an iPad for lessons on the New Testament. “I share my screen to do this really intimate work with an ancient language, and we’re all right there, present in the moment.”

Associate Professor of Psychology Cat Norris happened upon a benefit of virtual learning when her seminar students were set to read an article written by her friend Professor Helen Mayberg from the University of Colorado. Mayberg pioneered the development and use of deep-brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression.

“I thought, wouldn’t it be cool to have her pop into the Zoom and talk about that research project?” says Norris. “So we had our first ‘surprise’ visitor. The students’ faces were priceless: disbelief, awe, amazement.”

Guest speakers also have been a highlight of Wallace’s course that connects students to community partners and leaders in nearby Chester, easing the loss of in-person collaborations. A recent class welcomed Twyla Simpkins, founder/director of the Yes We Can Achievement & Cultural Center.

“Being able to learn from and with residents and community leaders who have experiences that are intimately connected to the scholarship we’re reading in class brings a whole new level of meaning,” says Katie Carlson ’23, of Duluth, Minn.

For all of the bright spots of the shift to virtual, there are significant challenges. Students and faculty are balancing coursework with the stress and danger of a global pandemic, caring for loved ones, dealing with financial insecurity, navigating time-zone differences, and more.

And, ultimately, nothing compares to being together in the classroom.

“It’s more difficult to moderate discussion, to read the students’ body language, to encourage that somewhat quiet student to jump in,” says Norris. “I miss engaging with them more casually, hearing about what’s important in their lives, and truly sharing in their Swarthmore experience.”

“What is missing is the connection between the textual and the real,” adds Everbach, stressing the challenge of moving his labs online. “Engineering is about turning stuff into things, and that is currently nearly impossible.”

Unable to share a space with students in his Introduction to Drawing course, Logan Grider, associate professor and department chair of art, says one of the main challenges has been that he can’t see what they see, or follow their decisions in real time.

“I’ve had to readjust my approach, delaying the entire teaching moment until after the drawings are completed,” Grider says. “It means losing valuable teaching opportunities.

“The students have all been wonderful and understanding, putting up with my clumsiness with all the tech,” he adds.

And then there is the complexity of moving a musical-performance class to a virtual setup.

You can’t have real-time musical collaboration of more than a few people online, notes Andrew Hauze ’04, senior music lecturer. Stitching together prerecorded videos of group members playing their own parts is “utterly different from that of making music in the same space with others.”

This fall, students in Hauze’s wind and orchestra ensembles rehearsed online weekly. Since they needed to mute themselves on Zoom, lest it “sound like utter cacophony,” Hauze couldn’t offer corrections or input in real time. In response, he made practice recordings for which he recorded each part on piano, overdubbed with all the other parts; students could download a recording for their instrument, with the sound of their own part in the right ear and the sound of the other instruments in their left.

“That way, when they’re practicing, students can be sure that they have the correct notes and rhythms and hear how their part fits into the whole,” Hauze says. “So we can focus on the bigger picture of how the music is put together during our weekly meeting.”

Also recalibrating opportunities for student collaboration was Assistant Professor of Art History Paloma Checa-Gismero, whose Arts & Craft as Avant-Garde Labor course this fall connected students from around the world through a communal crochet project.

“We sought to awaken the social spirit of collaboration by mailing to each other purposeless items that grew, in unexpected ways, throughout the semester,” she says. “From Swarthmore to New York to Pittsburgh to Norway and back, these objects embodied the questions and partial answers that the historians, artists, crafters, and theorists that we have read together describe.”

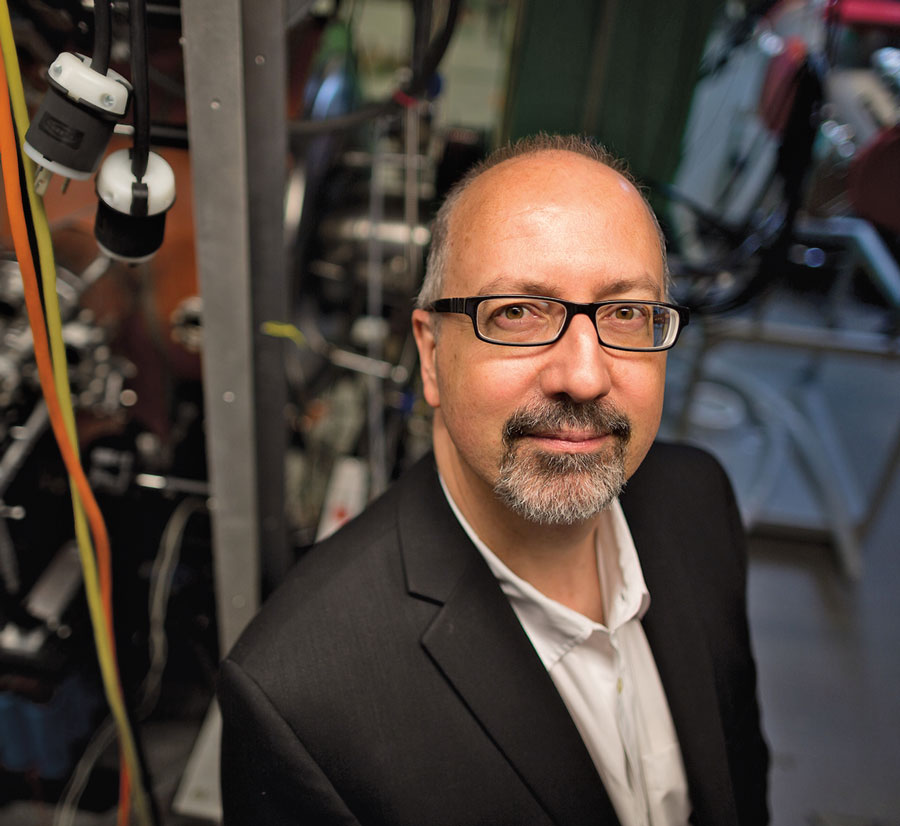

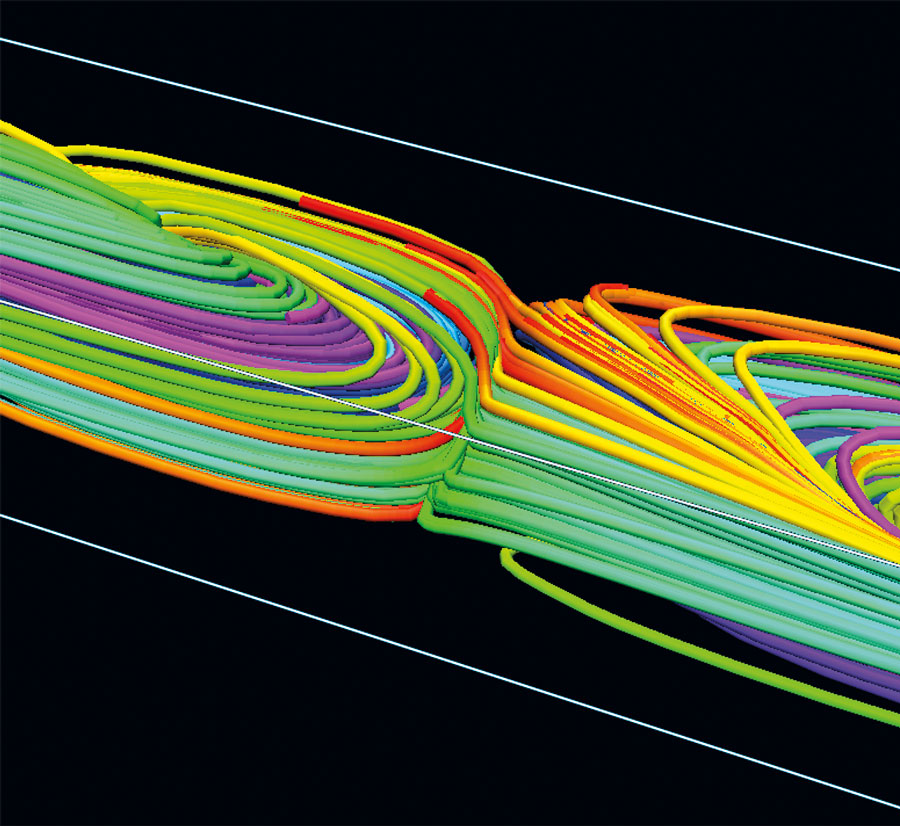

The group, composed of Josh Vandervelde ’23, Daniel Curtis ’21, and Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach, studied Swarthmore’s new wind tunnel, a 45-foot-long tube structure in Maxine Frank Singer Hall that allows students to extrapolate how aerodynamic bodies would fare in high-altitude flight.

Funded by a Richard Hurd ’48 engineering grant, their work this past summer lays the groundwork for future student projects, while also furthering the research started by Quentin Millette ’20 on kites that generate energy from powerful, high-altitude winds.

In order for the group to assemble and test their tools at home, administrative coordinator Cassy Burnett mailed soldering equipment and other supplies to Curtis in Macomb, Ill., and Vandervelde in El Cerrito, Calif.

“Even though we were separated, and it wasn’t in ideal conditions, I definitely learned a lot about the processes of team engineering,” says Vandervelde, and about “how many things can go wrong in a project, and just picking yourself up and continuing to go forward.”

Adds Everbach: “Engineering is all about the habits of mind, the meta issues — when something isn’t working, what do you do? How do you proceed? Those were the real important lessons learned.”

Eva Baron ’22 endured another muggy summer in her hometown of New York City, with the added layer of the pandemic.

“It was sluggish in a way that only being cooped up and apart from most people can make you,” says the honors English literature major. “It was refreshing to log back into Zoom and be greeted by the familiar faces of my classmates and professor.”

“Even through the computer screen,” she adds, the art seminar taught by Checa-Gismero “has reinvigorated a sense of curiosity, creativity, and reflection within me that I had somewhat abandoned during the summer away from academics and, of course, campus.”

Fostering such human connection has been a point of emphasis for faculty, including Associate Professor of Philosophy Krista Thomason. She entered the fall semester excited about her Peace and Political Philosophy class, for which students wrote real scholarly letters to one another and, as their final assignment, to Thomason.

“We’re far apart, and it’s an intimate form of communication: scholarly but conversational,” she says.

Whether classes are remote or in person, many of the same aspects of the student experience remain, says Riley. They can still feel that connection to Swarthmore.

“That’s something I can take away from this: that the efforts of faculty and staff to make adjustments as needed has been seen and appreciated by our students,” she says. “Having that contact with your professor, knowing they’re rooting for you, knowing they are doing all they can to help you succeed, goes a long way.”

Buoyed by this response, many faculty members say they feel empowered to take chances.

Navigating the shift to virtual learning is still a long and difficult journey, but one with growth and a renewed understanding of flexible thinking. “We don’t have to just shut everything down and hide under the covers and wait until this goes away,” says Wallace. “Are there opportunities there that necessity has triggered or brought to the surface that we wouldn’t have found otherwise?”

For many other faculty members and students, the stresses of daily life can preclude forward thinking, let alone optimism. But a consensus is emerging that while virtual classes are just that — virtual — they can also be grounding.

“Not only are our classes connected through a shared sense of something lost, but also in the shared knowledge we can gain,” says Ann Sinclair ’23, of Doylestown, Pa. “There’s a sort of comfort in the fact that, whatever is going on in the world, the equations we learn still work, the books and papers we read still have something to teach us, the discussions we have still open our eyes to new perspectives and ideas.”