I Was There!

Alumni look back on memorable, loud, live performances over the decades. Concerts by some legendary acts before they became famous shaped the experiences of those who were there.

by Ryan Dougherty

I Was There!

Alumni look back on memorable, loud, live performances over the decades. Concerts by some legendary acts before they became famous shaped the experiences of those who were there.

by Ryan Dougherty

“The stage might have been eight square feet crowded into the eastern end of the first floor; the band completely filled it,” remembers Beams. “ [They were supposed to be] the opening act, but played a long set.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” he says.

For Dave Scheiber ’76, the “magical moment” happened in the Scott Outdoor Amphitheater, as he and his friends were introduced to a sly, fedora-wearing dynamo.

“We knew nothing about [Bruce Springsteen], but it was a beautiful, balmy April afternoon, and a free show, so we went,” he says. “And from the instant the band took the stage, we knew we were experiencing a show unlike any we’d ever seen.”

Forty years later, all the way across campus in the Fieldhouse, Sean Anthony Bryant ’13 had his moment, watching Big Boi, half of the chart-topping rap duo Outkast, electrify a capacity crowd.

“He brought me and a handful of other Swatties on stage. It was awesome!” recalls Bryant, who later got backstage to take photos. “A night I’ll never forget.”

It’s hard to overstate the role such performances played for countless Swarthmoreans — the indelible memories they took away, the bonds built with classmates. Performances large and small, seen in all types of spaces across campus, imbued adventure into the flow of student life.

“As Swatties, you knew you worked harder, and those performances were the things you’d look forward to for months,” Bryant recalls. “When I look back at my time at Swarthmore, they are the nights that stand out.”

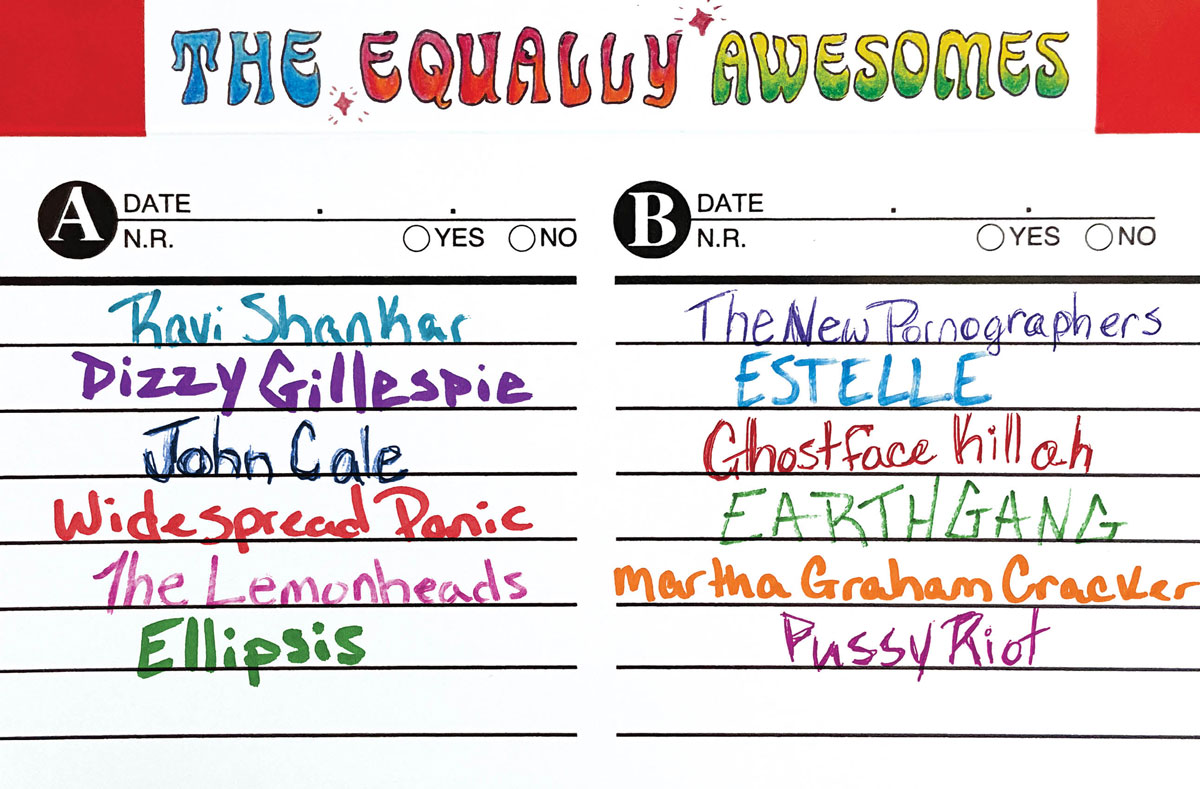

Following is a people’s history of legendary concerts at Swarthmore, whether for artistry or memorable circumstances — from internationally renowned rock bands to student a capella groups to folk singer-activists to chart-topping rappers. Memories of the finer points may have been lost to time, but not the feeling of having been there.

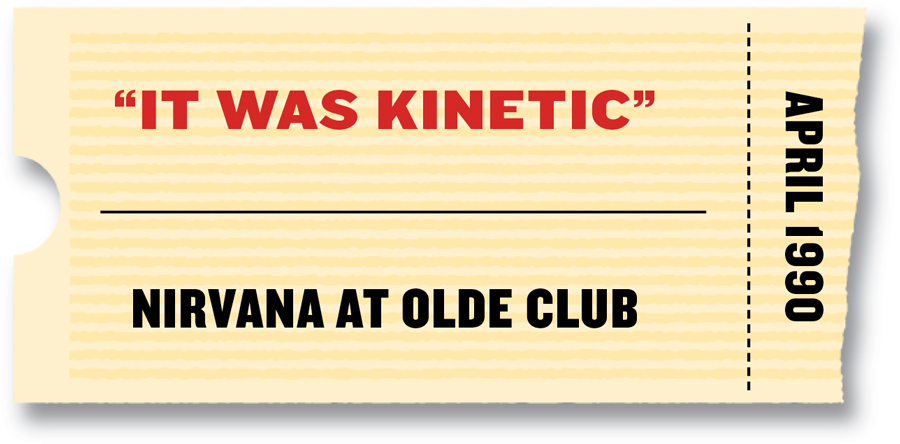

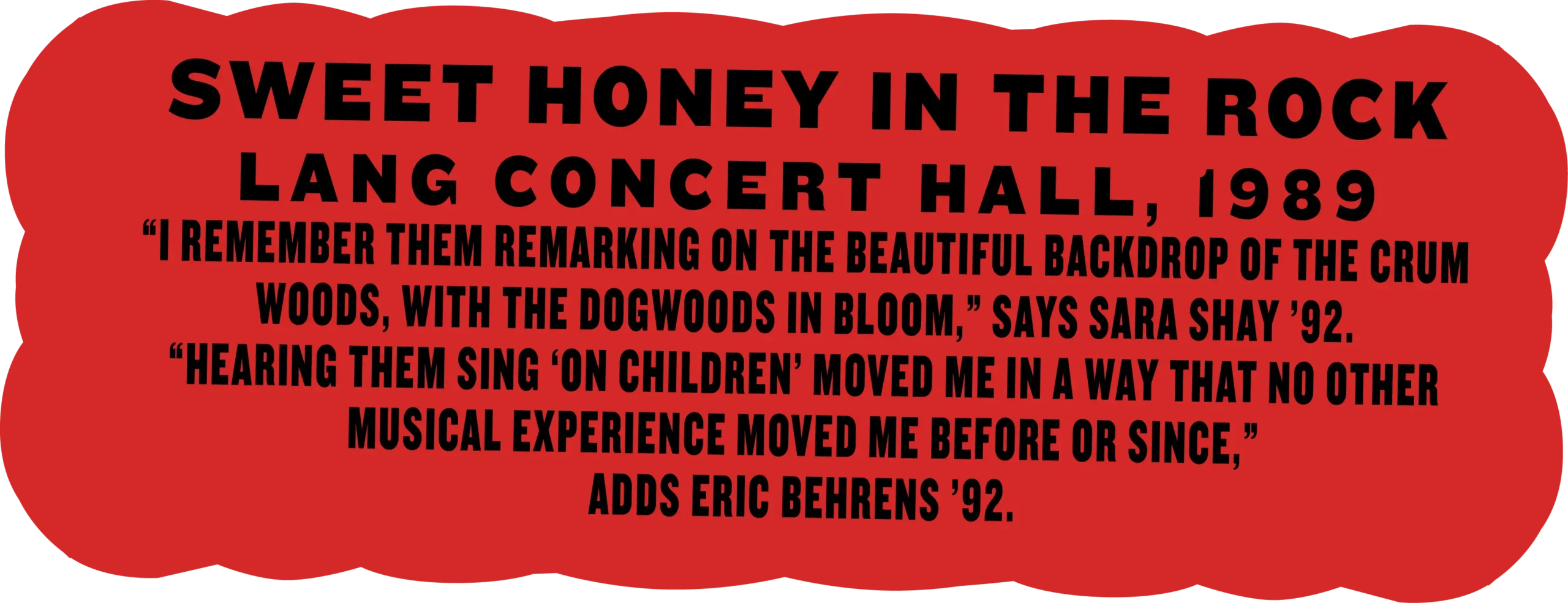

“It was kinetic”, Nirvana at Olde Club, April 1990

The calendar listing in The Phoenix heralded “Band in Old Club” [sic], and Nirvana’s name was hand-scrawled onto the posters made for the original headliner, Let’s Kill Larry.

“I remember listening to [Let’s Kill Larry] and looking back and seeing three guys in their soon-to-be-iconic grunge look listening to the music,” remembers Jim Ellis ’91. “They stood out, mainly because the bassist is 6’7.” I knew they weren’t students, so they had to be Nirvana.”

It didn’t take Beams long to realize he was seeing something special.

“It’s hard now to imagine how completely remarkable this felt at the time,” he says. “How unprofessional, how angry, how completely out of accord with anything commercially familiar, viable, listenable, or emotionally relatable to most people — even to college kids.”

“There couldn’t have been more than 50 people there, but it was kinetic,” Ellis says. “They were amazing — great energy and passion with catchy hooks and lyrics.”

There was no stage diving from the balcony, remembers Tom Lincoln ’93, “but the tatted visitors from the University of Delaware made the mosh pit much more punk.”

At one point, Beams says, someone passed a 12-pack of Pabst to the band.

“I remember [Cobain] taking a long gulp, then dashing the full can at the feet of the audience,” he says. “They drank and played and hurled cans out of the box at the stone walls behind and around us. It was wild!”

But the one thing everyone who was there remembers? How loud it was.

“Loud as f***,” says Jay Rhoderick ’92.

“So loud that we were plastered against the back wall,” adds Jennifer McLean ’93.

The volume caused Ben Schonberger ’93 to leave after two songs. Then, it hit a breaking point.

“Cobain blew out the new PAs we’d just acquired,” says Misha Lepetic ’94.

Those blown amps “floated around” for years, says Ethan Holland ’98, before finding a home in the club’s basement. Students sometimes sat on them or used them as tables.

“I assumed everyone knew they were sacred,” he says, “but apparently someone cleaned things up and threw them out. A rare time when I wish someone had just stolen them.”

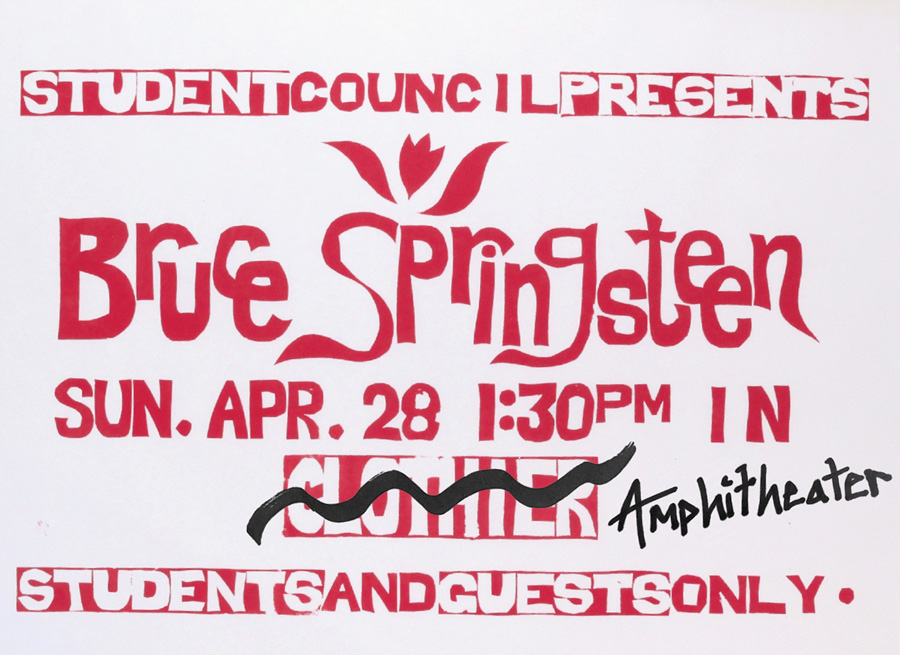

“Bruce Who?”, Springsteen in the Amphitheater, April 1974

But it wasn’t clairvoyance that brought Bruce Springsteen and the E-Street Band to campus that day. “It was a stroke of dumb luck,” says Stu Blair ’73, who booked the show with friend and WSRN co-host Don McNally ’73.

The duo considered more than 100 acts, many of which wouldn’t work because of scheduling conficts or cost, before picking the Garden State bar band with two albums out but little airplay.

“I remember telling folks that I couldn’t forecast future success, and that this year we’d just have to settle for fine, local music,” says Blair. “The common response was ‘Bruce who?!’”

It was a “quintessential Swarthmore spring” day, recalls Leonard Roseman ’74, with all of the trees and flowers in bloom. But it was also the prelude to reading week: Huck Flynn ’77 recalls seeing only about 25 attendees early on, and feeling bad for the band.

“I remember Clarence [Clemons] looking around like, ‘Is this it?!,’” Flynn says. “But then they cranked it up, loud, and people started streaming in. Classic Swarthmore students — studying until the last minute before a social event.”

Music wafted to the ’Ville, and soon the amphitheater was packed. Students and local residents enjoyed a “fantastic” and “hugely energetic” show, Flynn says, with a high-powered “Rosalita” encore and the first documented performance of the band’s signature hit, “Born to Run.”

“What stands out to me is how much fun that Bruce and the band were having playing with each other,” adds Kate Harper ’77.

“They played forever. We all missed dining hall dinner hours,” says Dave Bayer ’77. “The music was raw and original, and one sensed a legend emerging.”

Indeed, when Bruce Springsteen and the E-Street Band hit the national charts a year or two later, it didn’t surprise Mora Fisher Mattingly ’76.

“The atmosphere was electric, and everyone was having a great time,” she says.

There was, however, one notable downside: By the end of the concert, the amphitheater was a pigsty. But McNally had anticipated that, and enlisted a squad of helpers carrying yard-waste bags.

“Those folks left the grounds in pristine condition,” Blair recalls, averting reprimand from College administrators with Commencement just a few weeks away.

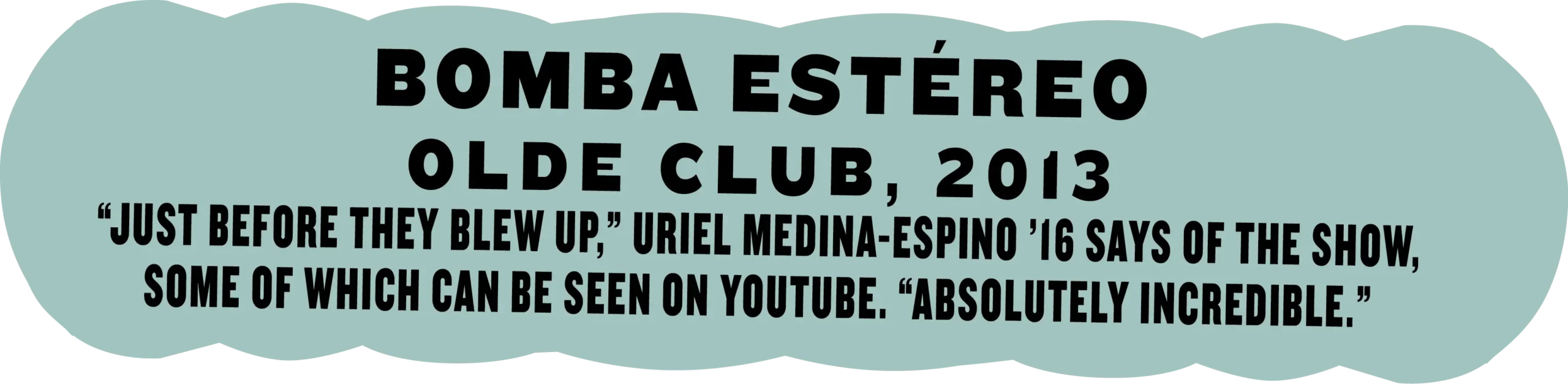

“A Testament to the Clumsy, the Sweaty, the Loud”: Olde Club Then and Now

In the mid-1980s, Olde Club became the go-to spot for smaller shows after a fire damaged Old Tarble. Student organizers reallocated the money allocated for one or two big concerts a year to bring 10 to 12 “up-and-comer” college radio acts to the club, recalls Matt Wall ’87.

In the beginning, it drew Philly-area acts like Anti-Flag and Electric Love Muffin, with a campus band opening. But Olde Club’s reach soon expanded to attract regional acts like They Might Be Giants and then national acts like Superchunk.

“Rodney Anonymous, the lead singer, lept up, grabbed the chandelier, and swung out over the crowd,” recalls Anne Wright ’88. “The chain broke, but the electrical cord held and kept the chandelier (and Rodney) from crashing to the ground.”

The Nirvana show is by far the most remembered, with students organizing a tribute show on the 33-year anniversary this April. But the club played host to an array of other nationally known acts from the ’90s and aughts, including Codeine, Spoon, The Magnetic Fields, Yo La Tengo, and members of Galaxie 500 and Animal Collective.

Kurt Leege ’94, a sound engineer, remembers the club as a “really unique space.”

“Because of some bizarre combination of the stone walls and the wood, when you hit a certain volume at certain frequencies — particularly with guitar and cymbals — the room would create an organic swirling effect,” Leege says.

Olde Club wasn’t the most aesthetically pleasing or comfortable place, alums say. But that only added to its lore.

“The staircase creaks, the bathroom sink sprays water everywhere, the basement is boarded up, but Olde Club feels worn-in, not run-down,” Samantha Herron ’18 wrote in The Phoenix.

“Nestled into the well-groomed bastion of academia that is Swarthmore,” she added, “Olde Club stands as a testament to the clumsy, the sweaty, the loud.”

“We are cursed to have them here”, A Flock of Seagulls at the Baseball Field, April 1986

From The Phoenix: “Opinion has been voiced [here] and over dinner in Sharples that these are the least favorite bands of anyone at the school, and that we are cursed to have them here.”

There was also a rumor, recalled by several alumni but not documented, that Bruce Springsteen offered to perform a free concert at Swarthmore that year, but the administration passed due to crowd control issues. Was A Flock of Seagulls a consolation prize?

Then the band came with a tour rider that, as Matt Wall ’87 remembers it, required a green room with a combat-camouflage theme to include toy guns. “Quite the Quaker touch, eh?” Wall says.

Heavy rain delayed the show for hours, and things devolved from there. Acoustics from the stage, on the baseball field, were “horrible,” Wall says, and the band “divas.”

Dawn Porter ’88, H’21 also recalls being less than inspired by the show. “People went for the free beer, and to dance to one song,” says Porter, the early MTV staple “I Ran.”

In a review for The Phoenix, Jon Blaine ’90 wrote “Flock of Seagulls was as cheesy as Modern English was obnoxious. They came out looking like a bad MTV video, and played as if they had recorded the whole thing beforehand.”

The passage of time has softened the sentiments of some attendees, who can appreciate hearing “I Ran” and Modern English’s “I Melt With You.” But the prevailing memory is disappointment.

“We were definitely not at Swarthmore at the right time,” writes Danielle Casher ’86.

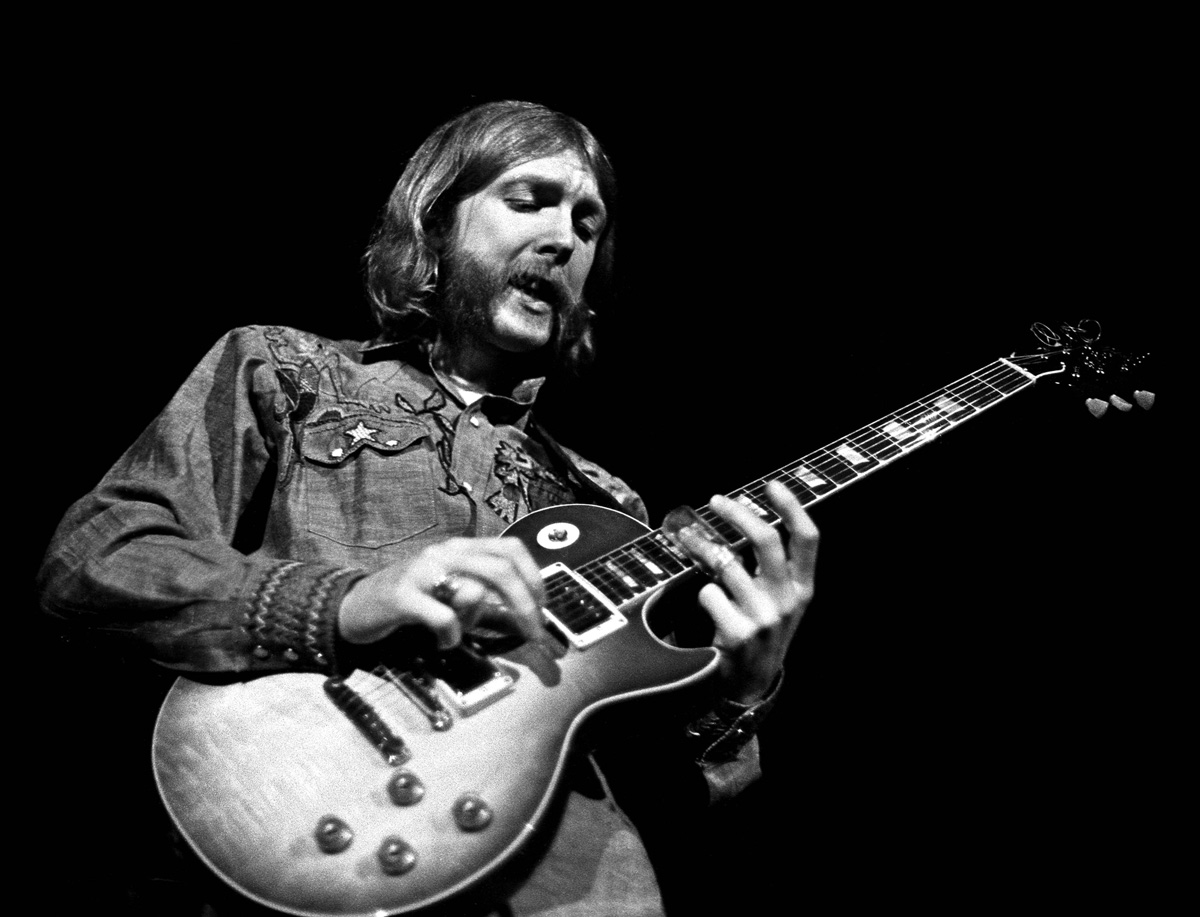

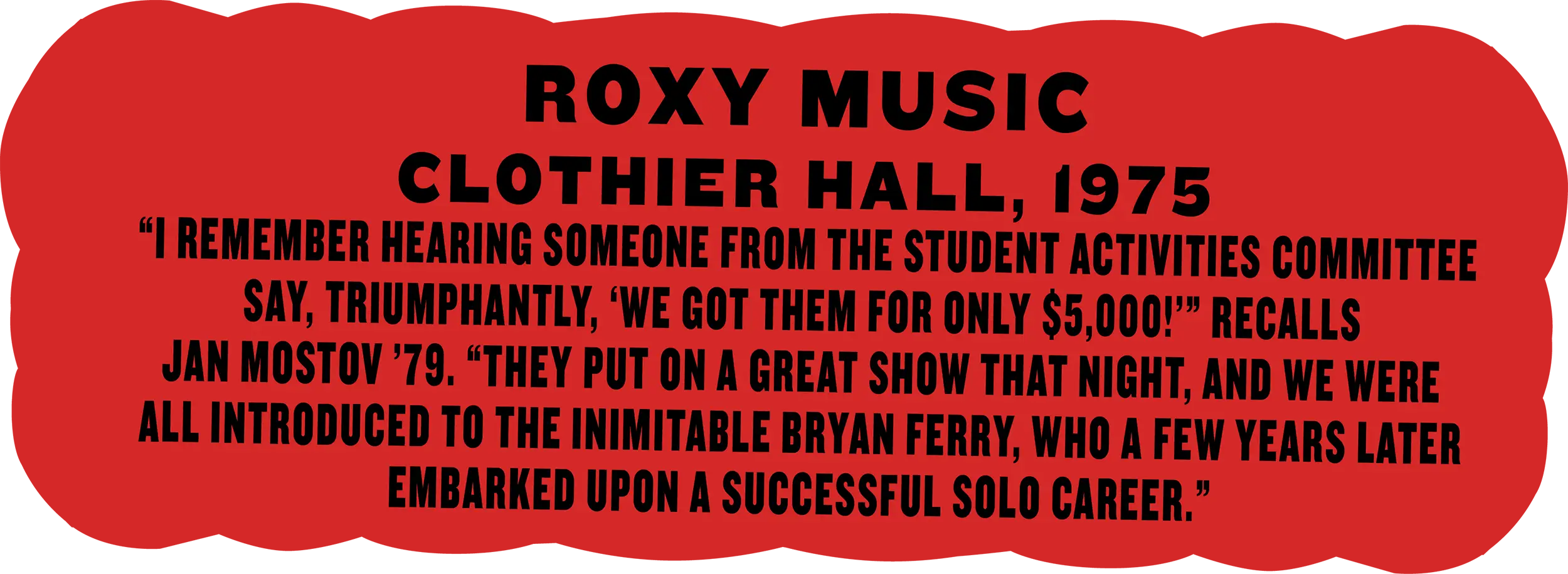

“So bluesy and cool”, The Allman Brothers in Clothier, May 1970

“They did their blues thing far into the night,” Seth Mellon ’72 wrote in The Phoenix. “They’re not innovators, but they did their thing very well indeed.”

The College pivoted to the rock festival after plans for an all-day, Woodstock-type event with eight to 10 bands proved too costly. This concert was free, but students had to pay a $1.50 deposit that was refunded at the door.

The show can be heard on YouTube, featuring signature hit “Whipping Post.” David Dye ’74, best known as long-time host of WXPN’s nationally syndicated “World Cafe,” offered background on the recording.

“The tape itself is a thing of legend; it had disappeared for at least three decades,” Dye added. “And when you listen to it, they’re so young … it just sounded so bluesy and cool.”

Dye also recalled the Allmans “threatening to go swimming” in Crum Creek — a nod to the gatefold photo in their first album of the band skinny dipping — and that a group of “campus radicals” took the stage at intermission to announce a bombing in Cambodia and implore the crowd to help them “figure out [their] reaction.”

“Everybody left, and there were maybe 20 people there for the second set,” Dye recalled. “That’s why you hear the band say, ‘Hope it was a good meeting.’”

Don Mizell ’71 Reflects on Gil Scott-Heron and Sun Ra

Mizell fell hard for Temple University’s jazz station, WRTI, and built relationships there that connected him to burgeoning talent.

Atop that list is Gil Scott-Heron, a jazz poet now regarded as the godfather of rap. Mizell, who had won an original poetry reading contest at Swarthmore, brought Scott-Heron to campus and also opened the show in 1970.

“We had maybe 30 to 40 people there in Bond Hall, and it was phenomenal.”

In his senior year, Mizell brought the eclectic jazz composer Sun Ra to campus — a most memorable performance from an act that, as Mizell remembers, trafficked in “the astro mystical.”

Sun Ra’s bandmates, some with painted faces, ran onto the stage chanting “It’s after the end of the world,” Mizell says, “which freaked everyone out.” Then a smoke bomb went off, and Sun Ra appeared with a robe and skull cap, “as if from outer space, just playing like it’s Judgment Day.”

“It could have been a Grateful Dead jam session, or something else trippy,” adds Mizell.

Mizell, too, made a musical mark on the school, fronting the Swarthmore student rock band Phaedra for a year.

“Anytime we performed on campus, it was packed,” he says. “I was trying to do a James Brown, Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix thing. Kind of psychadelic.”

Mizell did ultimately have something in common with that trio, after winning a 2005 Grammy for producing Ray Charles’ Genius Loves Company. In 2014, Mizell donated his Grammy to Swarthmore, and it now lives in the Black Cultural Center.

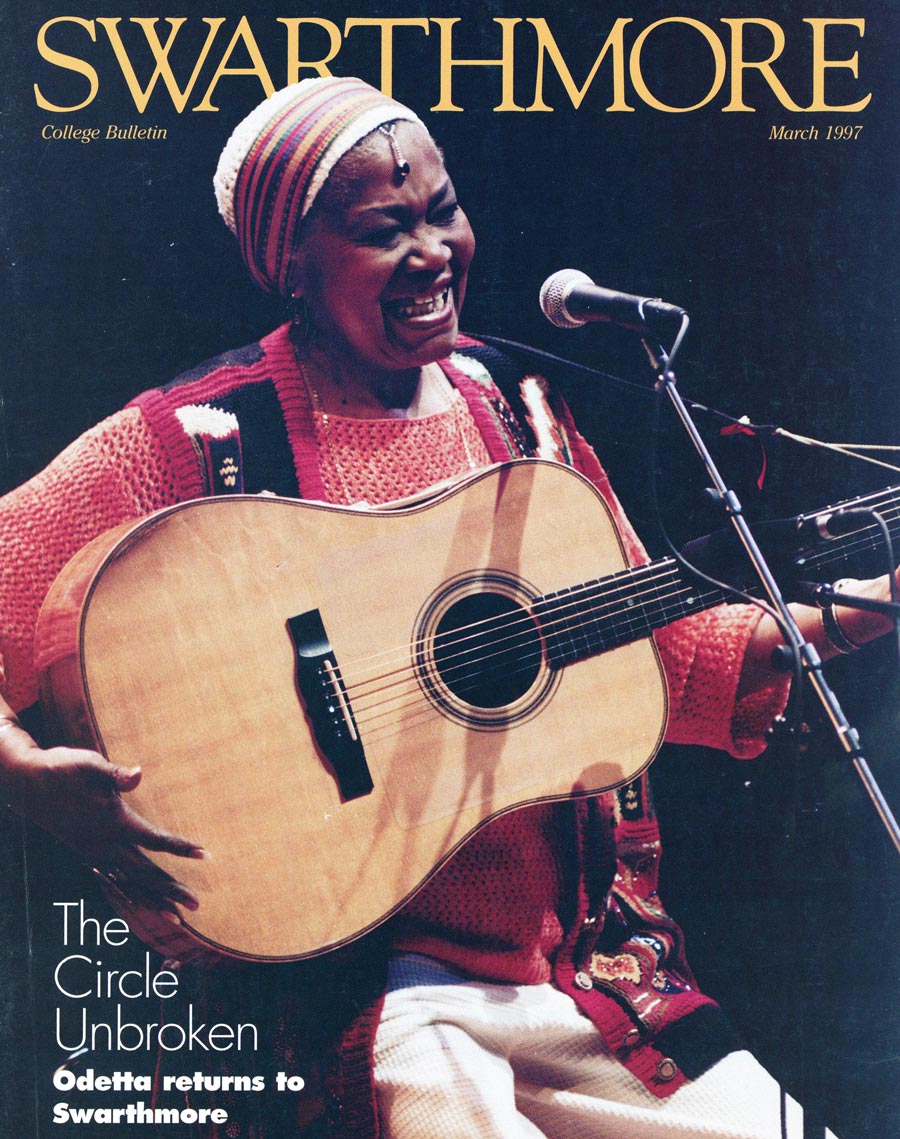

“Giants roamed the campus”, The Swarthmore Folk Festivals, 1945 – 1967

“I just remember her standing at the podium and singing with her whole being,” Palka says of the 1958 Folk Festival performance. “It was my introduction to her as a stunning performer, and to the role of music in powerful social movements.”

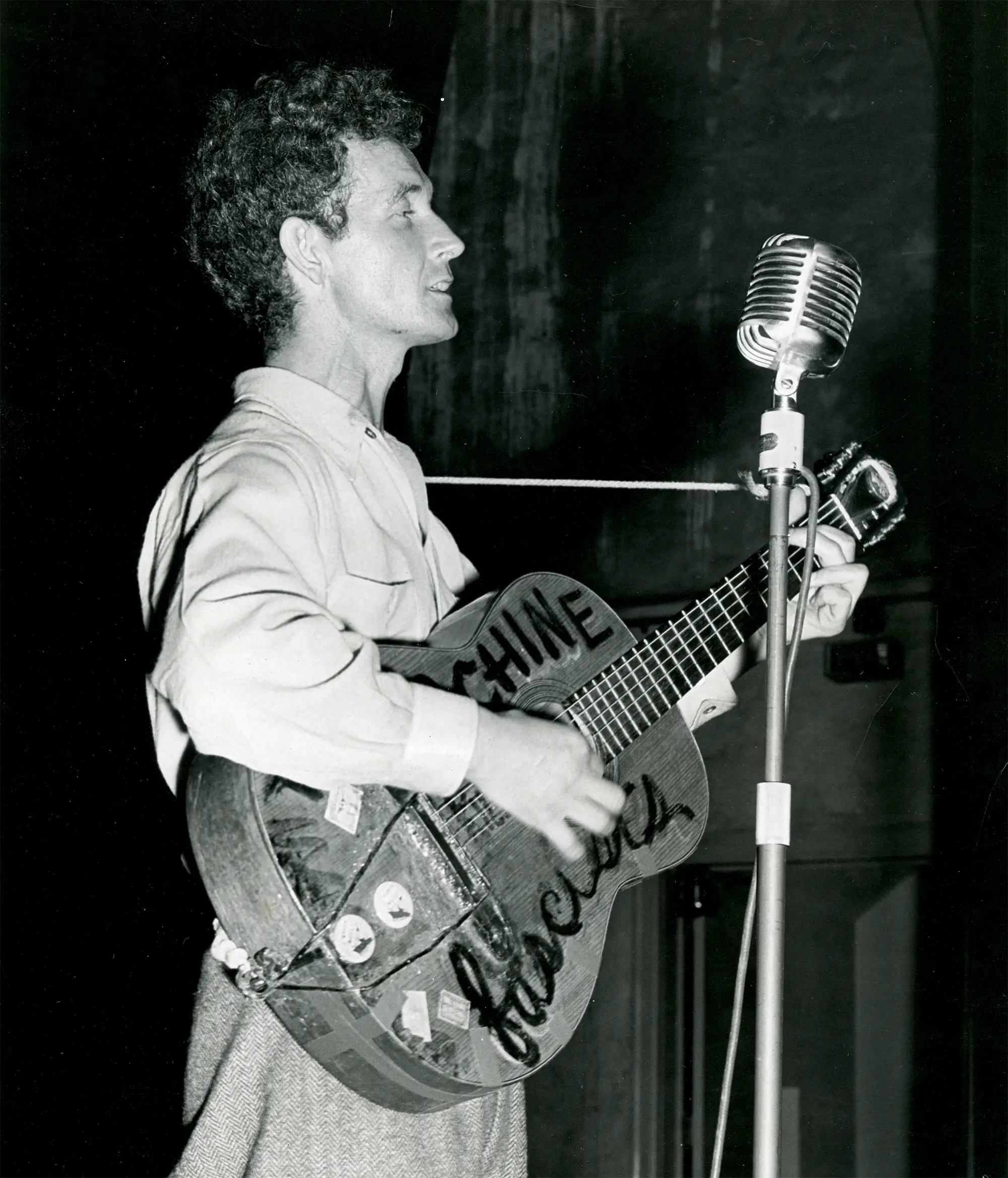

Such was the ethos of Swarthmore’s Folk Festivals, held between 1945 and 1967. They brought a remarkable array of acts to campus, from blues icon Lead Belly to folk giant Woody Guthrie to bluegrass inventor Bill Monroe to singer-songwriter superstar Joni Mitchell.

Pete Seeger’s performance in 1953 stands out for festival participant and historian Mike Meeropol ’64, “but the Reverend Gary Davis was unbelievable as well.”

Tom Webb ’66 had heard stories about earlier fests, “when people would come and sleep out on the lawn.” But his most memorable experience was Doc Watson in the amphitheater in 1963.

“Some amazing guitar playing,” Webb recalls, “and the thrill of sitting up close to a legendary musician.”

Watson returned two years later, teaming up with the co-headliner, Monroe, for an impromptu performance (part of which can be heard on YouTube).

Watson returned yet again in 2011, this time to perform at an Alumni Weekend concert in honor of the late folklorist Ralph Rinzler ’56, who is said to have “discovered” Watson at a recording session in 1960.

Another Folk Festival highlight was the country blues singer Lightnin’ Hopkins, who released his 1963 performance as an album, The Swarthmore Concert. Hopkins stayed on campus for a week, per The Phoenix, “jamming on a cot in the ML third lounge, much to the delight of students.”

By the late 1960s, however, the winds were blowing differently, and the College veered toward rock festivals. But the legacy of folk music on campus lives on.

“Some of those festivals just had superb talent,” says Stu Blair ’73, citing John Fahey, Stefan Grossman, Dave Van Rock, Danny Kalk, and Ramblin’ Jack as examples.

“Those were the days that giants roamed the campus.”

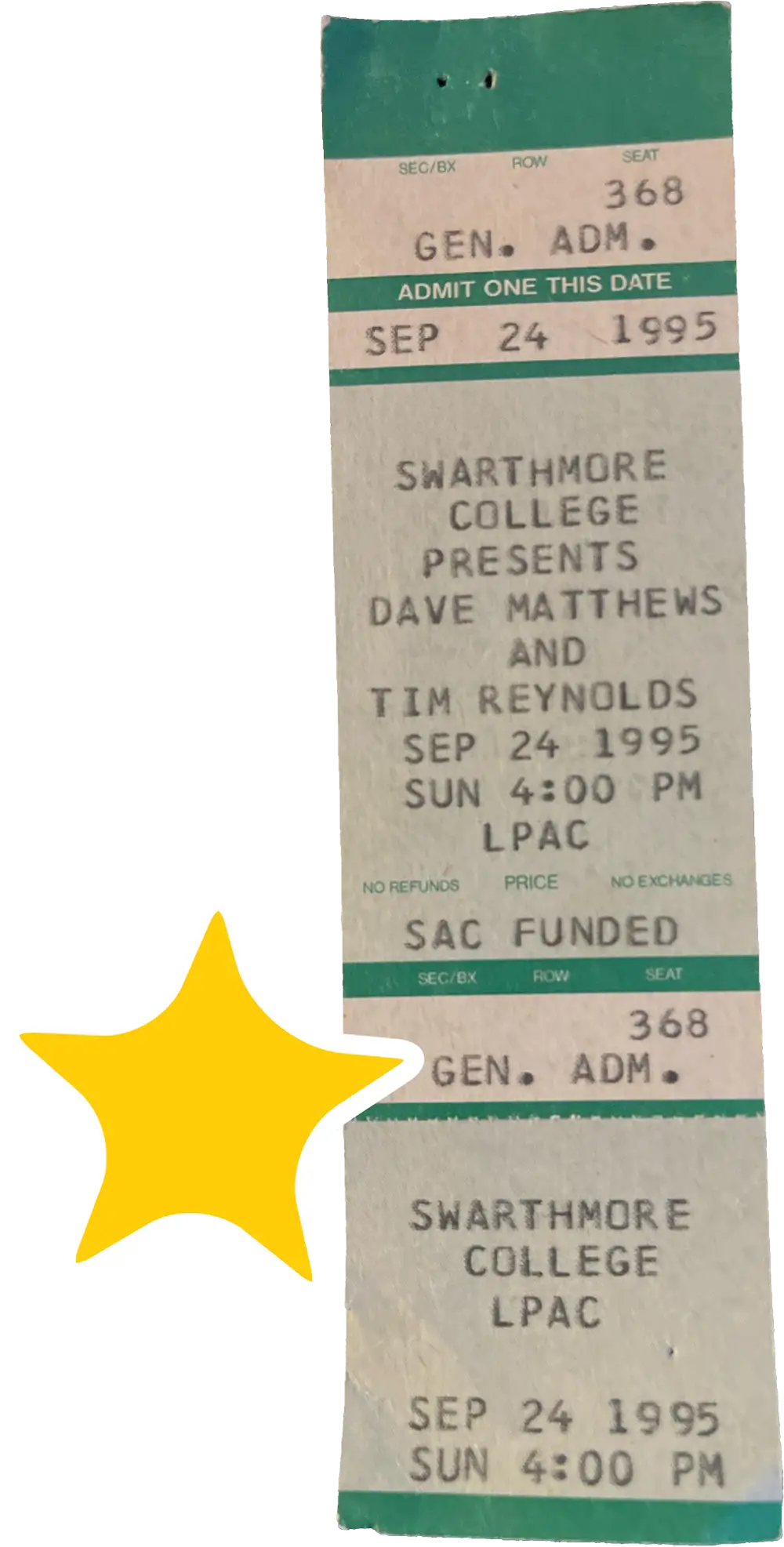

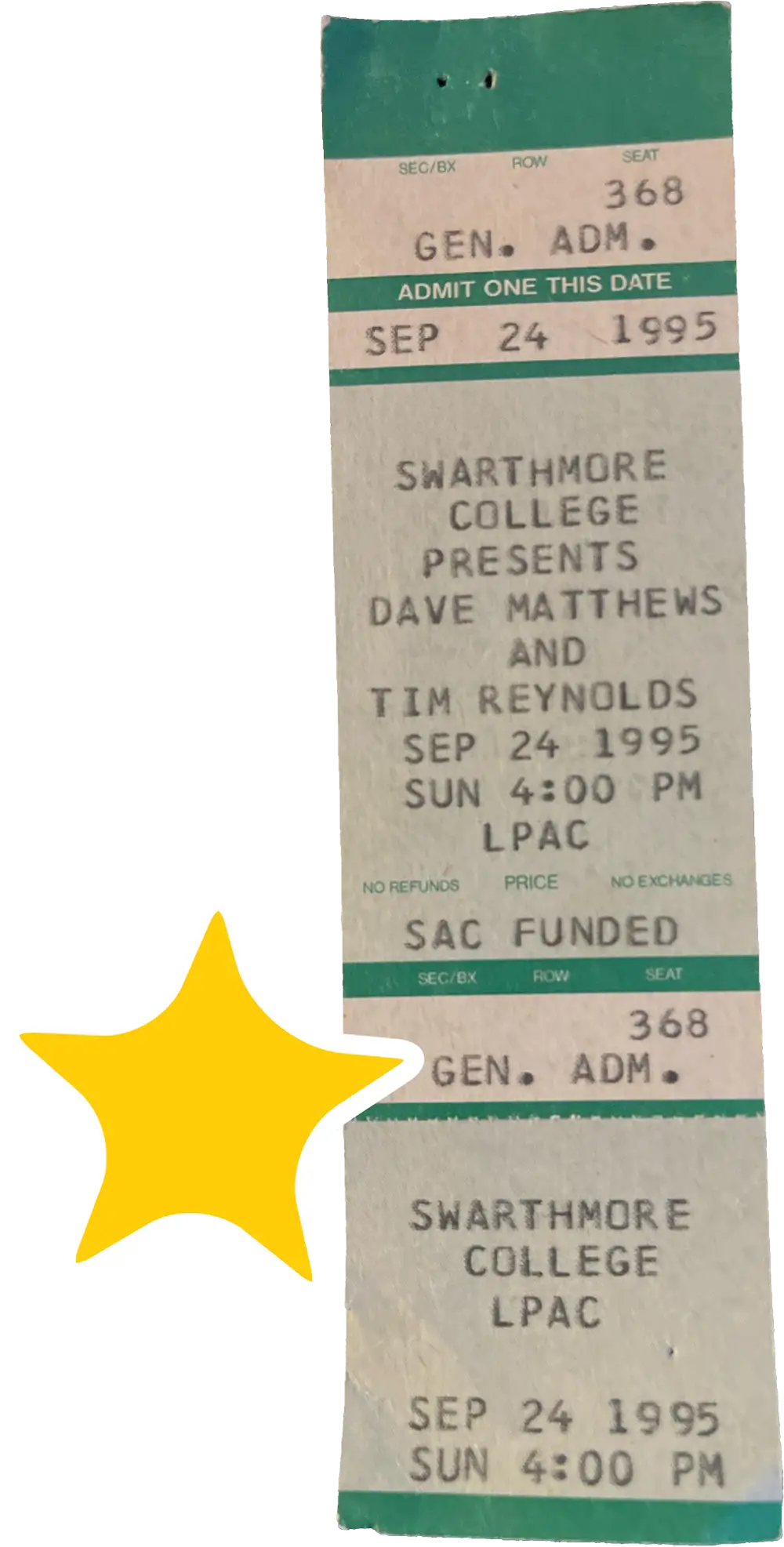

Dave Matthews and Tim Reynolds, 1995

This performance marks the first playing of future Dave Matthews Band hit “Crash into Me.” A friend of Matthews, Charlie Mayer ’98, told the student activities committee that the singer-songwriter was game to play Swarthmore. “I still have the cassette tape of the show,” says Anne Lund ’99. “People were actually leaving to go study!”

“Magical,” says Ashley Flynn Ward ’98. “An incredible night I will never forget.”

Matthews had just finished his summer tour and rented a house in Newburgh, N.Y., to work on songs for his band’s second album, Crash. “I had no idea the songs we heard that night would become the soundtrack of my Swarthmore experience and my young adulthood,” says Mayer.

Dave Matthews and Tim Reynolds, 1995

This performance marks the first playing of future Dave Matthews Band hit “Crash into Me.” A friend of Matthews, Charlie Mayer ’98, told the student activities committee that the singer-songwriter was game to play Swarthmore. “I still have the cassette tape of the show,” says Anne Lund ’99. “People were actually leaving to go study!”

“Magical,” says Ashley Flynn Ward ’98. “An incredible night I will never forget.”

Matthews had just finished his summer tour and rented a house in Newburgh, N.Y., to work on songs for his band’s second album, Crash. “I had no idea the songs we heard that night would become the soundtrack of my Swarthmore experience and my young adulthood,” says Mayer.

Jefferson Airplane, 1967

The College’s second rock festival also featured Tim Buckley and Philly band Woody’s Truck Stop (featuring a teenaged Todd Rundgren on lead guitar).

“The sound [in Clothier] was so loud I went outside and sat on the lawn to enjoy” the set by Jefferson Airplane, recalls Bennett Lorber ’64, H’96. “It was great.”

Pat Metheny Group, 1978

It was a warm, sunny day in October, recalls Scott White ’80. “Barely anyone was there, but it was magical, as the colored leaves fell almost in sync with the music.”

“You could hear it echoing all over campus,” says Kathy Pearce Gledhill ’80.

Peter van de Kamp playing piano

“Let us not forget him playing piano for Charlie Chaplin’s silent movies,” says Leonard Roseman ’74, who took astronomy courses from van de Kamp.

![The Gospel Choir, The Meeting House; “The [Swarthmore] Gospel Choir gave incredible concerts in the Meeting House, and had folks hanging from the rafters!” remembers Vaneese Thomas ’74, H’14 one of its founders. “Lots of good music!”](https://magazine.swarthmore.edu/assets/2023/06/sb-spr-sum-2023-there-bubble-02-scaled.webp)

Carole King, 1984

“She was campaigning for [presidential candidate] Gary Hart. Probably the biggest mainstream name to appear at the College while I was there,” says Matt Wall ’87. “She only did a half dozen songs at the piano, but it was excellent. She had a lovely banter with students before and after. She was really sweet.”

Tri-Co Chorus and Philadelphia Orchestra performance of Honegger’s Christmas Cantata

“Singing there in the early 1960s, Peter Swing trained us well at the start, and William Smith [associate conductor] skillfully merged the three choruses into a single group,” Kurt Christensen ’59 remembers. “And even now, it’s fun to say I once sang under the baton of Maestro Eugene Ormandy!”

john alston h’15

The first time that Alston, then an associate professor of music, conducted Mozart’s Requiem still resonates for Jessica Hobart ’91, who sang in the chorus. “I witnessed this one from the risers, but it was wonderful to be part of bringing it fully to life for him.”

The Roots, 2008

“The thing I remember most is they were humble enough to hang out with students and acquaintances of mine before and after the show,” says Matt Turner ’11.

Big Dipper, 1989

“I helped organize that show, and have great memories of that because the band only had their van to stay in, so I invited them back to my apartment in Media for the night and went thrift shopping with them the next day,” recalls George Hurchalla ’88, author of Going Underground: American Punk 1979-1989.

Renée Elise Goldsberry, 2018

The Tony award-winning actress and singer best known for originating the role of Angelica Schuyler in Hamilton performed through the Cooper Series.

“Truly breathtaking to witness such a brilliant artist perform in such a beautiful space,” recalls Raven Bennett ’17. “A magical evening!”

Peter Schickele ’57, H’80

A composer, musician, and author best known for his satiric performances of fictional composer P.D.Q. Bach.

“Who knew classical music could be so funny?!” says Mia Ong ’94.

Sixteen Feet

“I remember Sixteen Feet performing a cappella in the Bell Tower on the last day of orientation on a cloudless summer night in 1999,” says Carlos Duque ’03.

Blue Oyster Cult, 1973

“I remember it being so exceedingly loud that I retreated to my desk in McCabe and could still hear it,” says Drew Reynolds ’74.

Simone Dinnerstein playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations

“Her recording and interpretation of the Goldberg Variations had recently come to greater prominence, so it was very special to experience it in person,” Henry Clapp ’09 says of the performance, which followed a master class from Dinnerstein.

Suzanne Vega, 1987

“I still love her music and poetry,” says Nick Morse ’88.

“I vaguely remember seeing a student wearing a [Vega] T-shirt in the late ’80s,” recalls Deborah H. How ’89, “and that the shirt left out the first “r” in Swarthmore.”

Allen Ginsberg, 1978

“He set several Blake poems to music, but what I remember most vividly was his strange, high voice, his hunched-over posture, and the way he swayed in time to the music. For sheer oddness, it was an unforgettable evening,” says Jill Ottenberg Muscat ’82.

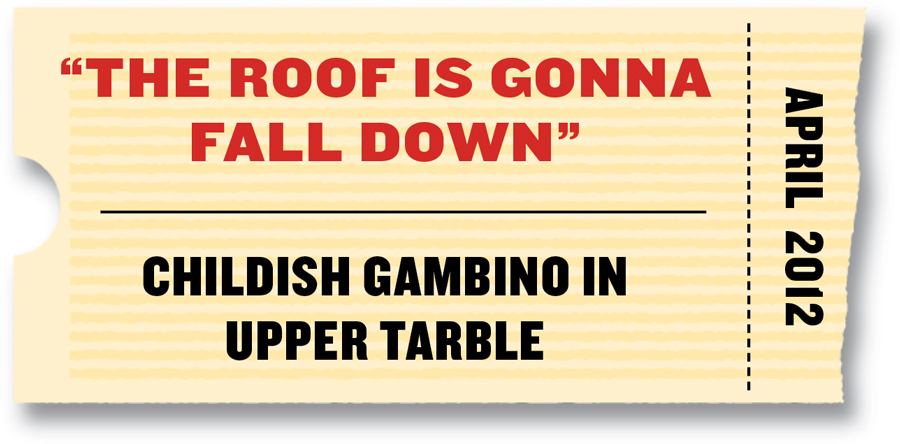

“The roof is gonna fall down”, Childish Gambino in Upper Tarble, April 2012

“Someone had to go up there and tell him … the roof is gonna fall down,’” remembers Brennan Klein ’14, who helped to organize the show.

“Upper Tarble was literally shaking,” adds Sean Anthony Bryant ’13.

Given the small capacity of the space, organizers had issued a limited number of wristbands. “But some clever students also made wristbands,” says Klein.

After the show, Glover tweeted, “Swarthmore, I apologize. I was told during the show that jumping could cause a collapse. Come to the Philly show to see a full performance.”

“Disappointment all around,” says Klein. “He couldn’t play the songs the way he wanted to, and there were a lot of students who wanted to be there, but couldn’t.”

Matt Turner ’11 left when the floor started shaking, but not before hearing Glover size up the scene.

“He said it was the weirdest crowd he ever played for,” Turner says.

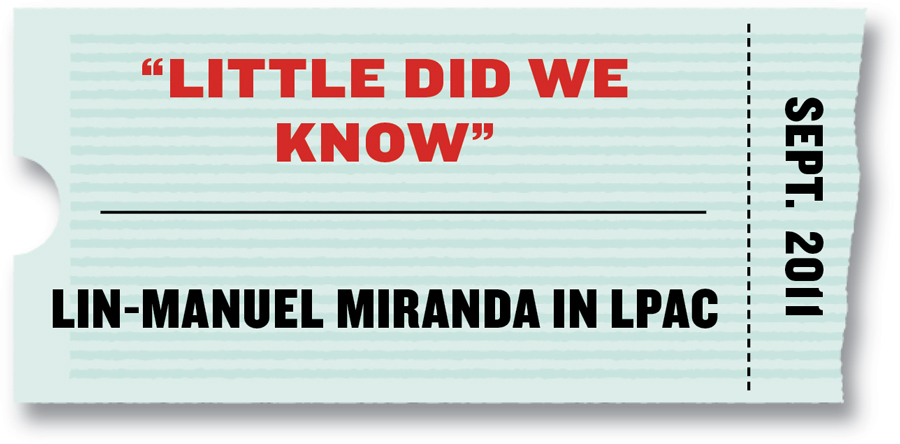

“Little did we know”, Lin-Manuel Miranda in LPAC, Sept. 2011

He spoke with a small group of students in the Intercultural Center, then for a larger audience in the LPAC Cinema. Most of the audience was either from New York City or knew people there who told them about “this brilliant new songwriter,” recalls Peter Schmidt, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English Literature.

“I remember they laughed skeptically when [Miranda] told them about his new project,” he says. “He laughed too, treating it like a really crazy idea. Little did we know.”

Miranda would, of course, soon cement himself as a Broadway legend with Hamilton.

He performed an early version of Alexander Hamilton’s opening rap, “My Shot,” and discussed how Latin music and 1990s hip-hop influenced him.

Rafael Zapata, then director of the Intercultural Center and assistant dean, was one of the many who helped bring Miranda to campus as a part of the Cooper Series.

A week before he visited, Miranda tweeted: “I’m speaking at Swarthmore next week. Every Latino Heritage Month, I get bombarded with invites like Harry Potter owl drops. #Lifeisgood.”

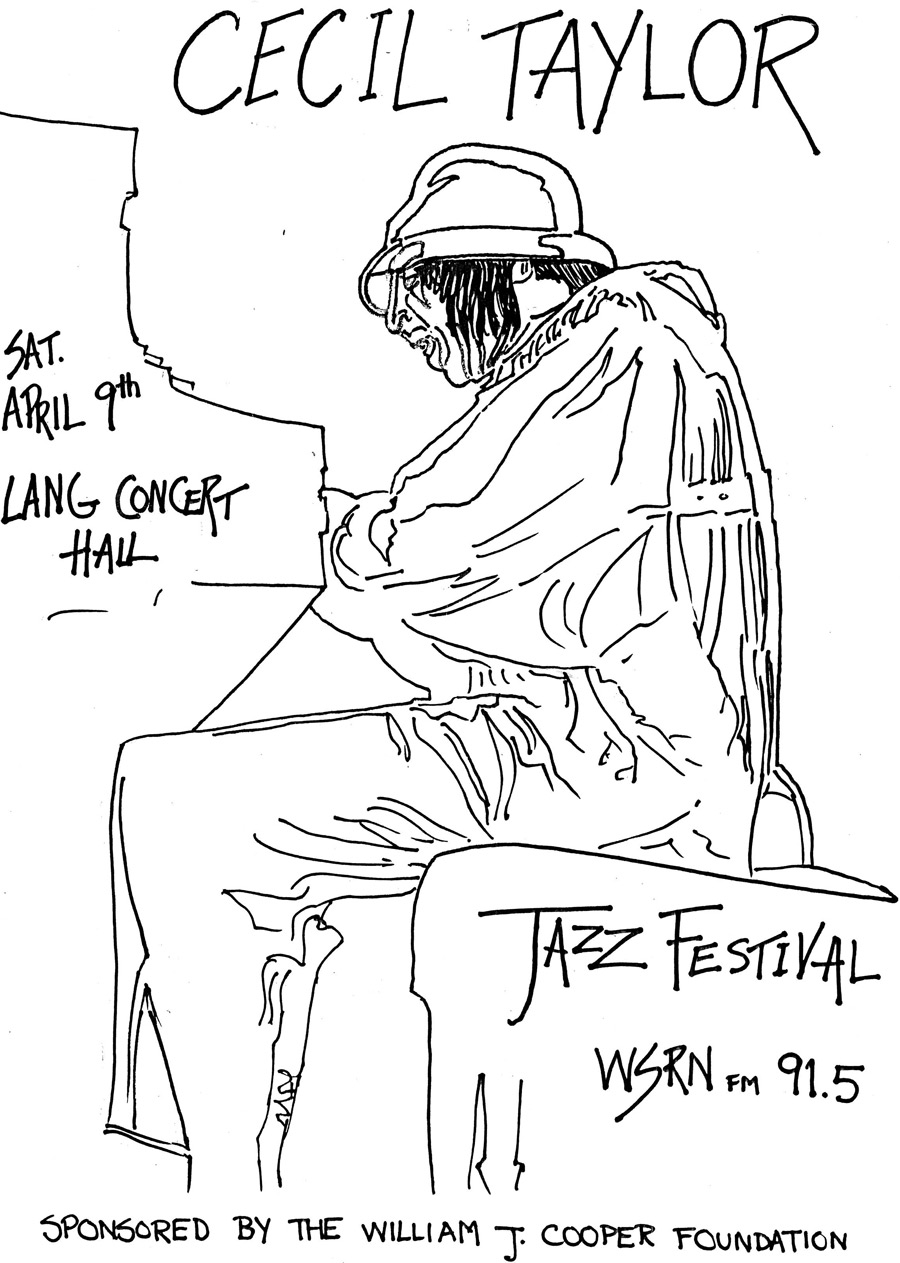

“Nothing short of life-changing”, Cecil Taylor in Lang Concert Hall, April 1988

Currie remembers it as the most ambitious staging of a jazz event in Swarthmore’s history to that point, and for him the performance proved “nothing short of life-changing.” After graduating with a degree in physics, Currie stayed in touch with Taylor’s bassist, William Parker, and studied African American music with saxophonist Makanda Ken McIntyre, of Taylor’s acclaimed Unit Structures ensemble.

While working on his doctorate in ethnomusicology, Currie won a grant to commission a new work from Taylor for an ensemble Currie founded.

Currie played baritone saxophone in the group, with Taylor leading from the piano, at the world premiere engagement at The Knitting Factory in New York City. He later got another grant, from the State Department, to perform the piece with Taylor and the band at the Skopje Jazz Festival in North Macedonia.

“In the end, I guess I can’t really credit my academic studies at the College, per se, though they were quite inspiring in their own way,” Currie says.

“But Swarthmore did give me the chance to pursue a dream that became my life’s work.”