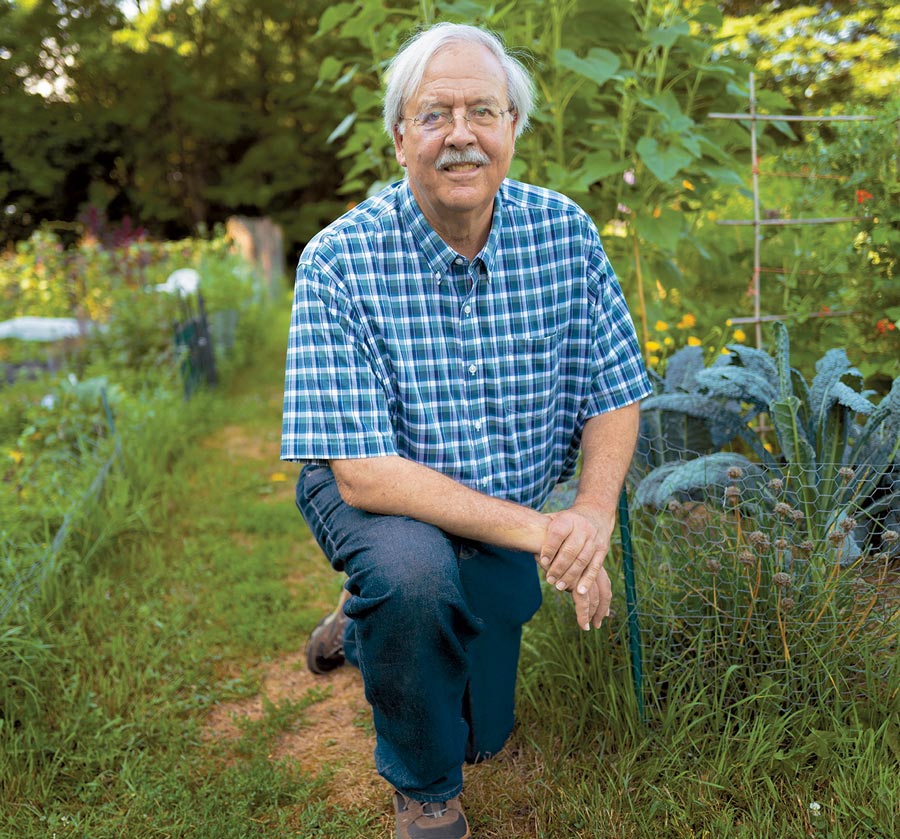

Leary looks to a future when sustainable agriculture practices are the norm. “We need to be able to grow food on this planet for a long time to come,” says Leary, at Kimberton CSA, a Pennsylvania community-supported agriculture farm, this summer. Today, Trees for the Future has 68 employees in Senegal and more than 200 across Africa.

swarthmore’s stewards are at work in the world and gaining ground

Pick a topic and dive in:

WASTE NOT: postlandfill.org

RESTORE: coral.org

GO DEEP: oceana.org

PLANT THE FUTURE: trees.org

ANALYZE: climateanalytics.org

A keystone species, the air-breathing, song-singing humpback whale eyes us up.

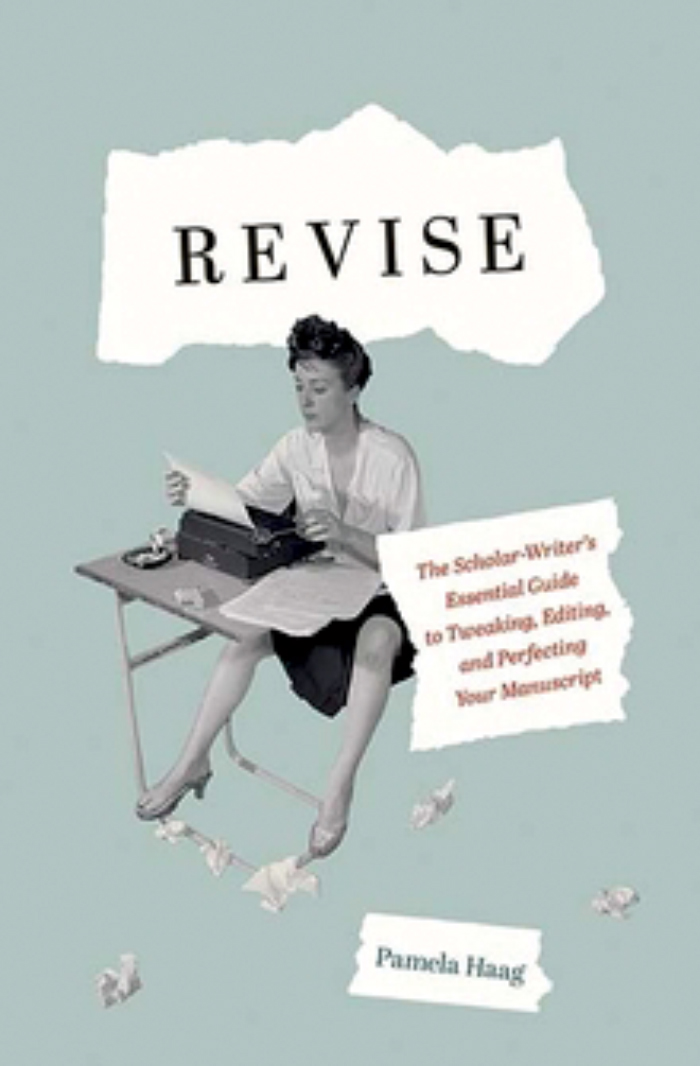

Ken Meter ’71

Sarah Bedolfe ’11

Define What Is Possible

campbell

In this Bulletin issue, as the campus welcomes all students back after a prolonged absence due to COVID-19, Swatties share ways they approach the work and care of planet Earth.

A tremendous task.

Through the collective crises of climate change, the continuing pandemic, humanitarian relief needs, global terrorism, and a blistering, hyperpoliticized culture war in the United States, Swarthmoreans continue to work through the ringing noise and define what is possible for an enlightened world.

Two takeaways: Start small and listen closely. John Leary ’00 literally begins with seeds in his quest to expand the presence of trees, collaborating with communities in sub-Saharan Africa to cultivate forest gardens. “We need a great-big reset in our food systems,” Leary says.

campbell

We share their stories and many more with the aim that they leave you as inspired — and hopeful — as they have us.

Together we can reach the surface.

Kate Campbell

Managing Editor

Elizabeth Slocum

Senior Editor

Ryan Dougherty

Staff Writer

Roy Greim ’14

Class Notes Editor

Heidi Hormel

Designer

Phillip Stern ’84

Photographer

Laurence Kesterson

Administrative Coordinator

Lauren McAloon

Editor Emerita

Maralyn Orbison Gillespie ’49

Email: bulletin@swarthmore.edu

Telephone: 610-328-8533

We welcome letters on articles covered in the magazine. We reserve the right to edit letters for length, clarity, and style. Views expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editors or the official views or policies of the College. Read the full letters policy at swarthmore.edu/bulletin.

Send letters and story ideas to

bulletin@swarthmore.edu

Send address changes to

records@swarthmore.edu

Printed with agri-based inks.

Please recycle after reading.

©2021 Swarthmore College.

Printed in USA.

On Our Radar

Pterodactyl Sighting

One was the feature on the Pterodactyl Hunt. Good to hear this zany tradition is alive and well. The main reason I decided to go to Swarthmore in 1987 was because I saw a poster advertising the Pterodactyl Hunt on a campus visit. I figured any college that hosted such a bizarre activity must be an interesting place to be.

The Hunt’s tradition may have spread. I introduced it to a summer camp up in Maine one year. Who knows how many Pterodactyls are flying around the world now?

all hands ON DECK

Unfortunately, by the time her son is her age, it’s possible the neighborhood could be underwater.

Sandy was just one in a barrage of recent record-breaking disasters related to climate change. Each of the past four decades has been hotter than the one that preceded it, and the seven hottest years in recorded history occurred within 2014–2020.

studentwise:

When I Couldn’t Go Home

hroughout my three years as a Swattie, and especially in light of the global pandemic, no community has impacted my journey more than i20, Swarthmore’s international student club.

I grew up in Singapore, and my first experience at Swarthmore was at International Student Orientation, way back in 2018. Entering that warm, welcoming, understanding environment created by other international Swatties set the perfect first impression of Swarthmore. It made me feel like I belonged, that this was somewhere I wanted to be for the next four years. I made fast friends and stayed involved with the i20 community throughout freshman year.

studentwise:

When I Couldn’t Go Home

hroughout my three years as a Swattie, and especially in light of the global pandemic, no community has impacted my journey more than i20, Swarthmore’s international student club.

I grew up in Singapore, and my first experience at Swarthmore was at International Student Orientation, way back in 2018. Entering that warm, welcoming, understanding environment created by other international Swatties set the perfect first impression of Swarthmore. It made me feel like I belonged, that this was somewhere I wanted to be for the next four years. I made fast friends and stayed involved with the i20 community throughout freshman year.

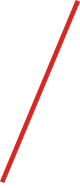

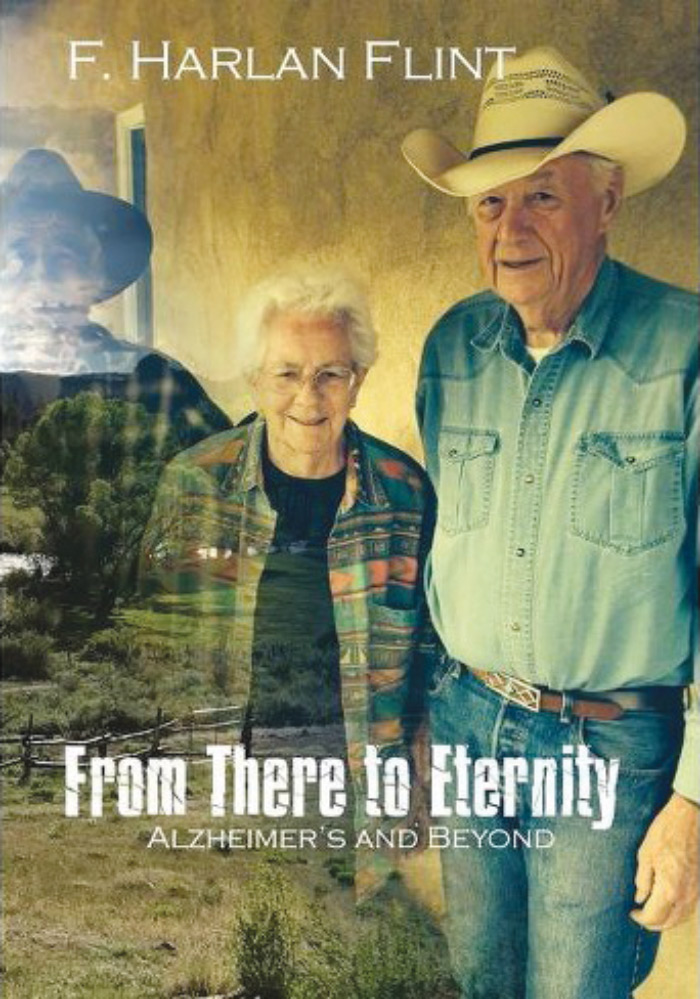

HOT TYPE: New releases by Swarthmoreans

F. Harlan Flint ’52

From There to Eternity: Alzheimer’s and Beyond

Sunstone Press

Pamela Haag ’88

Revise: The Scholar-Writer’s Essential Guide to Tweaking, Editing, and Perfecting Your Manuscript

Yale University Press

Below the Surface

An in-depth understanding of ocean life

In 2001, her adviser from the University of California, Berkeley, was to be the one near the bottom of the sea studying the habitat of the stomatopod, or mantis shrimp. But he couldn’t get medical clearance for the saturation dive. Although Fox’s interest was in coral reef conservation, she couldn’t say no to the amazing opportunity.

common good

Ten students will tackle sustainability challenges through the President’s Sustainability Research Fellowship.

A rare “corpse flower” bloomed on campus this spring, giving off its characteristically rancid smell.

Ryan Arazi ’21 and Madison Snyder ’21 were awarded Fulbright grants to continue their studies abroad.

Students Return to Campus

Capping Off an Unusual Academic Year

The events represented the culmination of four years of exploration and growth for seniors, spirited instruction and collaboration with the faculty, and multifaceted support of staff members from across campus.

forever be proud: “You are venturing into a world of extraordinary uncertainty, but also of great promise and infinite possibility,” President Valerie Smith said in her Commencement address. “You will leave here and form a union with purpose. And we will forever be proud to call you graduates of Swarthmore College.”

She Led

by Example

This Spring, President Valerie Smith shared the sad news that Constance Cain Hungerford, the Mari S. Michener Professor Emerita of Art History and Provost Emerita, died May 12 after suffering a stroke. She was 73. With her passing, Swarthmore lost one of its most distinguished, influential, and beloved figures and one who served the College confidently as provost and interim president.

“Connie took her training and talents as an art historian and translated these gifts for detail, visuality, and context, cultivating the ability to see uniquely issues that faced the faculty and the College,” says Provost and Dean of the Faculty Sarah Willie-LeBreton.

untangling the web

“It blew my mind,” Williams says of the document born out of the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991. “It showed me that environmental justice is really more of a lens that forces us to challenge the distinction between humans and the environment and think about how the health of the environment reflects the health of the people, and vice versa.”

Feeding Hope

“They’re launching farms among marginalized communities so people can feed themselves and build support networks,” he says. “It’s gratifying to see that energy crystallize after so many years of laying the groundwork.”

Meter hopes his new book, Building Community Food Webs (Island Press, 2021), will advance their efforts. In it, he shows how industrial, commodity-centered food systems drained wealth from communities, and he “highlights some of the most innovative projects I’ve worked with.”

Feeding Hope

“They’re launching farms among marginalized communities so people can feed themselves and build support networks,” he says. “It’s gratifying to see that energy crystallize after so many years of laying the groundwork.”

Meter hopes his new book, Building Community Food Webs (Island Press, 2021), will advance their efforts. In it, he shows how industrial, commodity-centered food systems drained wealth from communities, and he “highlights some of the most innovative projects I’ve worked with.”

Sea Change

“The ocean is a beautiful, amazing place, and I reconnect with it whenever possible,” she says. “It’s definitely a place where I feel happy and at home.”

Now a marine scientist at the nonprofit Oceana, Bedolfe wants the ocean to retain its appeal as a place for recreation and awe-inspiring creatures — and as a source of livelihood. Oceana has offices around the world and coordinates with conservation groups globally to find ways to sustain the oceans and implement national policies to protect them. Bedolfe is part of the organization’s science and strategy team at its headquarters in Washington, D.C. The team’s goal is to provide scientific research for conservation projects in 10 countries. Their efforts include evaluating potential new projects based on threats to marine biology, government systems, and the feasibility of solving their problems. “What I love about my job is that I get to collaborate with my colleagues around the world and connect them with one another and provide resources,” she says.

In Deep

rowing up in rural Kansas, Martin Tomlinson ’23 experienced the effects of the climate crisis firsthand.

“I saw my neighbors’ crops failing and the water in the creek behind my house beginning to dry out,” says Tomlinson, a double major in peace & conflict studies and religion with a minor in environmental studies. “As my town became more and more abandoned, I began to realize that this was the death of a way of life and of a community.”

An Existential Toolkit for climate anxiety

Her environmental studies classes had once been full of upbeat nature lovers hoping to make careers of protecting the Earth. But something had shifted, Ray says, leading to long lines for her office hours and lots of tears.

“The students were despairing about how the Anthropocene has hit, and we are in this moment where humans have irreversibly affected nature,” says Ray, a professor at Humboldt State University in California with a background in the humanities and social justice. “This is no longer about protecting something. This is about human survival in a radically altered future.”

In Deep

he sea abounds with show-stealers. Dolphins burst like rockets through the wave crests. An octopus’s lyrical suctioned army of arms transfixes. The blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus , weighing up to 330,000 pounds, sends its whistles, moans, and calls through water for thousands of miles. And when the giant marine mammal gives birth, mothers nimbly nose newborns to the ocean’s surface for their first breaths of precious air.

Consider, too, the ruthless stealth of the lowly mantis shrimp. This 6-inch ocean citizen releases a jaw punch to its prey with a strike force so ferocious it can delimb a crab. The blow, measured at 15,000 newtons, equals the acceleration of a .22-caliber bullet.

For Swarthmoreans at work in the world’s (now five) named oceans, the water’s inhabitants — both behemoth and near invisible — captivate.

It wasn’t only the mantis shrimp’s power that first fascinated Rachel Crane ’13. It was also the crustacean’s technique.

“I left Swarthmore with a deep love of invertebrates, biomechanics, and marine systems,” says Crane, who studied “beautiful lugworms” with Professor Rachel Merz at the College before graduating to the mantis shrimp as a lab manager at Duke University.

“They’re really interesting, with the most amazing mouth parts. Their jaw is like a bullet in the muzzle of a gun,” she says. “It has a super-fast, amazing strike.”

When Crane noticed how masterful mantis shrimp were at cracking open shells, she began to wonder if they approached each prey differently.

he sea abounds with show-stealers. Dolphins burst like rockets through the wave crests. An octopus’s lyrical suctioned army of arms transfixes. The blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus , weighing up to 330,000 pounds, sends its whistles, moans, and calls through water for thousands of miles. And when the giant marine mammal gives birth, mothers nimbly nose newborns to the ocean’s surface for their first breaths of precious air.

Consider, too, the ruthless stealth of the lowly mantis shrimp. This 6-inch ocean citizen releases a jaw punch to its prey with a strike force so ferocious it can delimb a crab. The blow, measured at 15,000 newtons, equals the acceleration of a .22-caliber bullet.

For Swarthmoreans at work in the world’s (now five) named oceans, the water’s inhabitants — both behemoth and near invisible — captivate.

It wasn’t only the mantis shrimp’s power that first fascinated Rachel Crane ’13. It was also the crustacean’s technique.

“I left Swarthmore with a deep love of invertebrates, biomechanics, and marine systems,” says Crane, who studied “beautiful lugworms” with Professor Rachel Merz at the College before graduating to the mantis shrimp as a lab manager at Duke University.

“They’re really interesting, with the most amazing mouth parts. Their jaw is like a bullet in the muzzle of a gun,” she says. “It has a super-fast, amazing strike.”

When Crane noticed how masterful mantis shrimp were at cracking open shells, she began to wonder if they approached each prey differently.

The Color of Trees

The Color of Trees

As it turns out, seeing the forest for the trees was more important anyway.

Today, Leary is executive director of Trees for the Future, a nonprofit with a vision to change lives through regenerative agriculture and help farmers “plant themselves out of poverty.”

It’s an urgent mission, says Leary: “If you don’t know where your food is coming from, it’s probably causing harm to some family or community somewhere.”

When Leary was a Peace Corps volunteer in the early 2000s, the seeds of friendship took root with his homestay brother, a Senegalese farmer. The two began planting trees together. Little did they know that they were preparing the ground for a sweeping movement that would bring tens of thousands of farmers hope, health, and opportunities to create a sustainable future for themselves and their families.

Laurence Kesterson

trees in front of parrish

— Libby Murch Livingston ’41

tree near parrish and Clothier

— Rob Lewine ’67

Sequoias

— Bennett Drucker ’22

lilac grove near trotter

— William Liang ’87

trees in front of parrish

— Libby Murch Livingston ’41

tree near parrish and Clothier

— Rob Lewine ’67

Sequoias

— Bennett Drucker ’22

lilac grove near trotter

— William Liang ’87

The Shadow of Hunger

My first year at Swarthmore in 2005, I gained 20 pounds.

This is certainly not unusual for freshmen, but in my case, it was for atypical reasons.

During my undocumented childhood, a period of extreme poverty that I never dared speak of during my time on campus, I arrived at elementary school every day starving, stomach churning toward the free meal that would be slopped onto my tray at lunchtime. For decades thereafter, the shadow of hunger lived in my stomach.

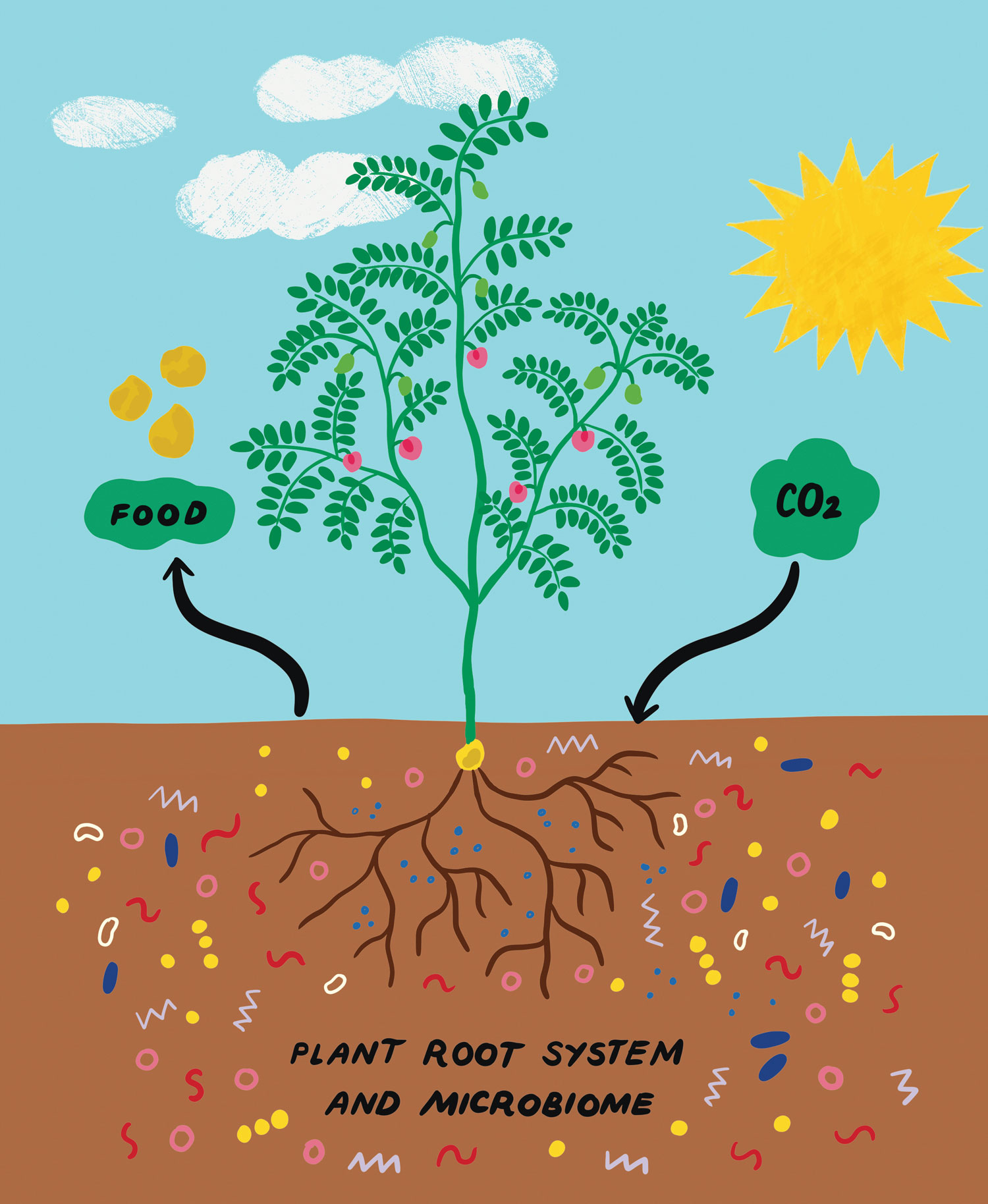

From the Ground Up

illustrations by Ayang Cempaka

class notes

Join us in this series, held remotely this fall, to hear knowledgeable speakers and engage in lively conversation with local community members as well as Swarthmore staff, faculty, and alumni.

swarthmore.edu/discussion-group

See a list of upcoming SwatTalks or browse the full catalog of recordings.

bit.ly/SwatTalks

Explore recorded events, upcoming programs, and ways to engage with alumni and students.

swarthmore.edu/alumni

Interested in serving your fellow Swarthmoreans? Nominate yourself or another alum for Alumni Council by Nov. 1.

bit.ly/SwatACNoms

their light lives on

A medical missionary and pacifist with a dedication to knowledge, service, and family, Bill died March 31, 2021.

Bill served with the American Board for Foreign Missions in Turkey and helped establish the Child Health Institute. He later worked for the New York City Department of Health and taught at Columbia School of Public Health.

Mary Ann, a retired administrator with R.H. Macy & Co., died April 13, 2021.

With a bachelor’s in social science, Mary Ann pursued studies in education at Columbia University. At Swarthmore, she was part of the Hamburg Show and participated in mountaineering.

Francis, an engineer, a musician, and a late-in-life runner, died Jan. 29, 2021.

Francis enlisted in the Navy V-12 program and studied at Haverford College, Swarthmore, and Duke University. After returning from World War II, he earned a master’s in electrical engineering and worked for Westinghouse’s nuclear business for 30 years before running a successful consulting business until age 70.

“Betita,” a leader in the Chicana movement, died June 29, 2021.

A former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee coordinator, Betita helped create the Chicano Communications Center in New Mexico. She later ran for California governor and helped found the Institute for MultiRacial Justice.

Howard, an undercover case officer who received a Career Intelligence Medal from the CIA, died May 3, 2021.

Howard left the College to enlist in the Army in 1944 and earned a Bronze Star in the Battle of Munich. After his honorable discharge, he joined the CIA, retiring at age 65 and working as a contract employee until 2005.

Frank, a physician and professor of radiation oncology who successfully treated a snow leopard with jaw cancer, died Aug. 10, 2019.

Frank received his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College, was a general medical officer in the Navy, and spent his career at what is now Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Upon retirement in 1996, he was presented with the Chicago Radiological Society Distinguished Service Award, and an endowed chair was named for him at the medical center.

Bill, who was board president of the Hudson (Ohio) Library and Historical Society, died May 3, 2021.

Bill served in the Army during the Korean War and worked for Sherwin-Williams Co., including as president of the International Division, retiring in 1993. He traveled extensively with his wife overseas and on study tours with the Victorian Society in America, and he was active on the Hudson (Ohio) Planning Commission and in his Unitarian Universalist church.

looking back

One hundred years ago, the Russian famine of 1921–1922 severely afflicted the Soviet Union, its effects lasting for years and claiming millions of lives.

International relief organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee sent extensive aid to the suffering areas. Jessica Granville-Smith Abt (known as Jessica Smith), Swarthmore Class of 1915, spent years in Russia as a Famine Relief Program worker with the AFSC.

Smith’s famine-relief work marked the beginning of her lifelong dedication to promoting Russian-American relations. She authored many books and articles, was an editor of and contributor to the New World Review for more than 40 years, served on the Board of the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, and was awarded the Order of Friendship of the Peoples by the Soviet Union in 1977.

Schofield. “They’re a tremendous group of people, and faculty in large part don’t interact with many of them on a regular basis.”

Clear and Transparent

What interested you about this role?

I worked on a committee with Professor of German and Film & Media Studies Sunka Simon, who held this position prior to me. I realized that there was a lot of work still left to do and that she had laid some great groundwork for things that I was interested in. When I first graduated from Swarthmore, my original goal was to be a middle school principal. So this feels a little like I managed to get back to that role without actually having to do the really difficult job of being a middle school principal. My original thinking in wanting to be a principal concerned the concept of what makes good teaching: what is involved and what support systems an institution can provide so people can develop their teaching and professional skills. I’ve been able to do a lot of that in this role, both in the recruitment of and the development for junior faculty.

What initiatives stand out for you?

We’ve tried to clarify and make more transparent our review procedures and policies for our tenure-track candidates as well as the reviews for our non-tenure-track instructional staff. We had them in place, but there were often a lot of questions. We held listening sessions with people who had recently been up for tenure to see what their experience was, chairs of all of the departments and programs, and the staff members who manage the process. I’m really proud of that because I think that transparency has really improved the process for our candidates as well as for the College generally. I’m hoping the transparency and clarity will mean less implicit bias in the decisions that we make because we’ve laid out a set of criteria much more clearly. That’s a very small way to be a part of a broader movement around anti-racism and anti-chauvinism.

this side up

Just as funny upside down, a treasured Monty Python poster makes the cut for Move-In Day on Aug. 23.

— Mwangangi Kalii ’23

Give back like Mwangangi by mentoring current students. Learn more at swarthmore.edu/alumni.

— Mwangangi Kalii ’23