From the Ground Up

illustrations by Ayang Cempaka

The Root of the Matter

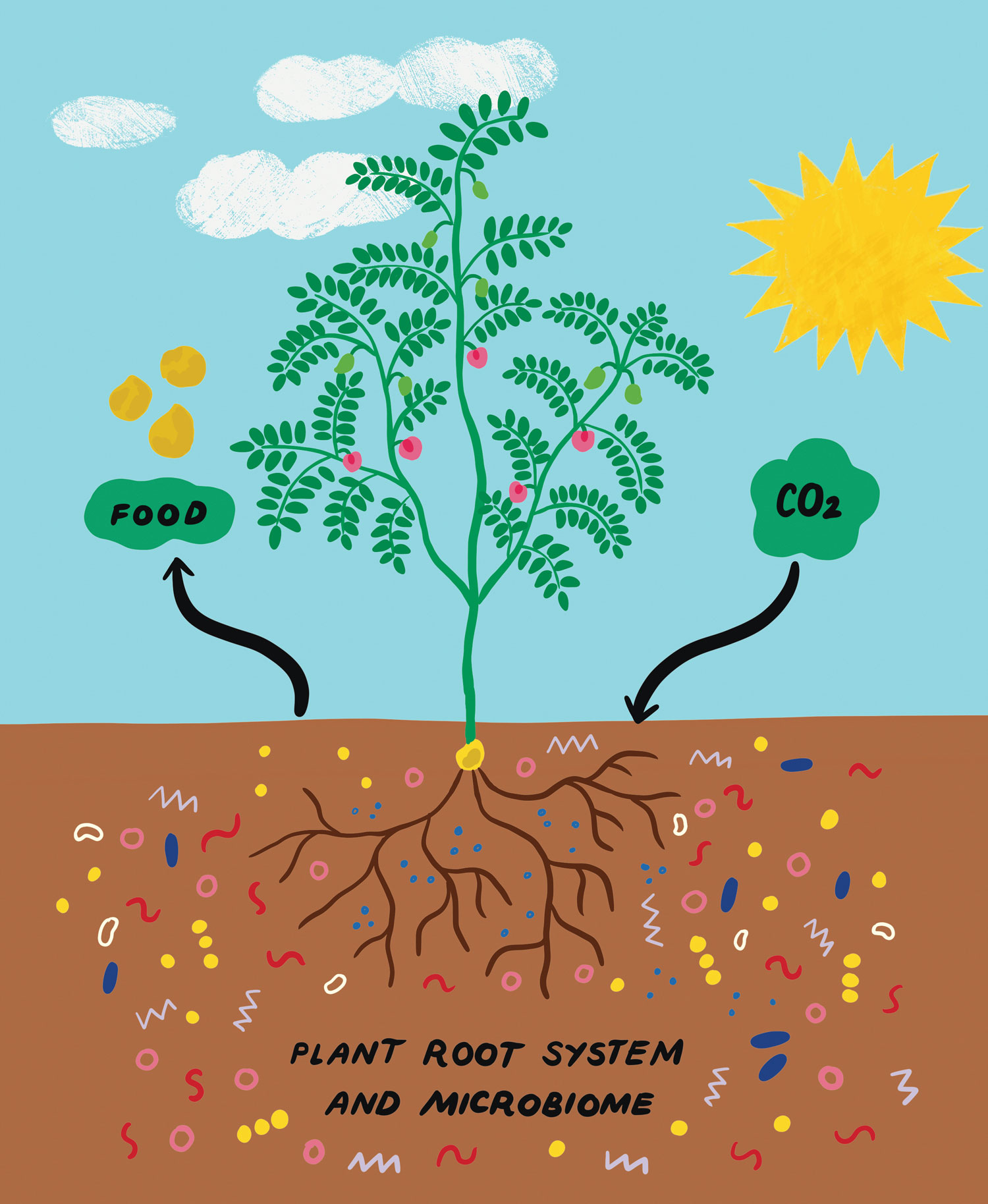

An associate professor of plant and soil science at the University of Vermont, von Wettberg studies root systems in chickpeas and other legumes to better understand the relationship between crops and carbon. By comparing the roots of domesticated plants with those of wild varieties, von Wettberg and his research team aim to improve the carbon-capture process, to the benefit of crops and the surrounding soil.

“At some point, we need to take the carbon out of the atmosphere,” says von Wettberg, a biology major at Swarthmore with a Ph.D. in ecology and evolution from Brown University. “Because soils can hold 10 times more carbon than the atmosphere, and because in agricultural soil, putting more carbon into it generally makes it better, the most ethical place to put carbon at scale is into the soil.

“If we want to achieve that, we need to understand how our crops came to put less carbon into the soil.”

Since the dawn of agriculture, crops have been selected for their output of seeds, with attention focused on their growth above the ground, von Wettberg says. As a result, farmers inadvertently selected for crops that put less back into the soil, with weaker root systems that thrived only in tilled land.

Wild chickpeas, meanwhile, grow on mountains and in deep rock in their native Turkey, their roots better suited for unideal growing conditions. By cross-pollinating these varieties with cultivars in the lab, von Wettberg’s team aims to improve genetic diversity while building climate-change resistance into agricultural systems.

“Da Vinci famously said that we know more about the celestial bodies than we do the ground beneath our feet,” von Wettberg says. “We have struggled to understand what goes on below, because to assess a root system, you basically have to take a shovel and dig it up, and that’s inherently destructive.”

Plant root systems can be compared to the human digestive tract, von Wettberg says, with the microbiome playing a large role in their health. “Plants are taking up water, nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium from the soil,” he says, “and their efficiency at doing that is in large part determined by how well they interact with the millions of microbes in that soil.”

how to liberate that frozen feeling and build some climate momentum as temperatures rise: Alumni notebook

— Eric Bishop von Wettberg ’99

“Be an advocate. Give to causes that are getting engaged in lobbying. It’s a really important time right now; with the change in the administration, climate change is way back on the agenda. And be an educated consumer. Read good books, like Michael Mann’s The New Climate War.”

— Polly Ericksen ’87

“Some people like being more hands-on, by joining a community garden or meeting like-minded people. That’s always a good start: finding a community that’s interested in the same things and being physically involved in it, to be more connected and rooted.”

— Eriko Shrestha ’19

how to liberate that frozen feeling and build some climate momentum as temperatures rise: Alumni notebook

— Eric Bishop von Wettberg ’99

— Polly Ericksen ’87

— Eriko Shrestha ’19

Von Wettberg says expanding the typical Western agricultural rotation to a four-crop system would further benefit plant and soil health and help diversify farmers’ incomes. One plan he’s exploring would round out the corn and soybean rotation with winter wheat and mung bean, a quick-growing legume often used in East Asian and Indian dishes. Though mung beans aren’t widely popular yet in the United States, von Wettberg wouldn’t be surprised if they took off.

One food company, he notes, Eat Just Inc., recently created a plant-based egg, catering to those Americans cutting animal products from their diets — often in the name of helping the planet.

The product’s main ingredient? Mung beans.

Ruminating on Ruminants

Livestock accounts for 14.5% of global greenhouse-gas emissions, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, largely the result of the methane they produce through ruminant digestion. These findings have led to global calls for reforms on how cattle are raised, as well as to how meat and dairy products are consumed.

“There’s a lot of data in Europe and in North America on how cows digest, on where carbon can be stored in agricultural situations, on how people will change their behavior and respond to different incentives,” she says. “None of that applies to smallholder farming situations in Africa, where people keep livestock for different reasons. They’ve adapted to a host of not just climatic but other kinds of stressors as well.”

A history major at Swarthmore with a master’s in economics and a Ph.D. in soil science, both from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Ericksen has spent more than 20 years working on agricultural development, natural- resource management, and global environmental change in developing countries. At ILRI, a global nonprofit research organization based in Nairobi, Kenya, Ericksen spends much of her time correcting assumptions about global livestock production while driving home the realities of African systems in climate change discussions.

“We’ll never be able to feed every cow in Africa with the resource intensities that you can in the U.S.,” she says. “There isn’t enough land, there isn’t enough money, there isn’t enough fertilizer. One thing we have learned is that you need different solutions for different systems. It’s important that we not take solutions from America and impose them on African smallholders, where the rationale and the profit margins for livestock-keeping are really quite different.”

In addition to elevating the agricultural data from underrepresented regions, Ericksen works with public- and private-sector partners in those areas on addressing and adapting to climate change. Improving the quality of cows’ feed baskets can significantly reduce their carbon output, Ericksen says, as can managing manure in confined feeding operations. “We’ve also found that the health of animals has a big impact on their productivity and is another promising opportunity to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions,” she says.

“But the challenge for the livestock sector is how will you ever get to total emissions reduction, because ruminant digestion will always produce methane,” she adds. “That’s why we need to look at land-based mitigation options for livestock systems.”

Model Behavior

As an implementation specialist at Climate Analytics, an international organization that advises partner countries on solutions to climate change, Eriko Shrestha ’19 works closely with nations to identify measures they can take to reach their emissions goals.

“We talk to government stakeholders, sometimes private-sector utilities, and we make recommendations — identifying the lowest hanging fruit for them to tackle, and then moving up from there,” says Shrestha, whose regions include the Caribbean and her home country, Nepal. For a target that focuses on renewable energy, for example, Shrestha’s team might create a scenario combining diesel generators with wind, solar, and geothermal power. Following a series of simulations, the team will devise an action plan, taking into account “what’s feasible financially as well as in the time horizon, and what’s existing on the ground in terms of infrastructure.”

Though based in New York, as a native Nepali, Shrestha understands the country’s unique circumstances. In her role she works directly with a small on-the-ground team in Nepal as well as with the nation’s Ministry of Forests and Environment.

“There’s also an ethical component in that we work with developing countries that aren’t historically responsible for the emissions, yet they’re the most vulnerable to climate change,” she adds. “So they’re more inclined to be more ambitious to pressure more industrialized countries to do the same, and improve their own resiliency against disasters because rebuilding is costly.”

A political science and environmental studies major at Swarthmore, Shrestha took an interest in climate policy as a Lang Opportunity Scholar, working on an electronic-waste management project in Kathmandu. Frustrated by the difficulties she encountered surrounding hazardous waste and recycling, she realized the importance of government policy in laying the groundwork for environmental reform.

“Now, my take on policy is that we need to work in the private sector, because there’s a lot of nudging that needs to be done,” she says. “It’s an evolution of me learning how things work, and figuring things out from there.

“This is clearly a complex issue that one person can’t solve. How can we all be part of the solution?”