Something of an Adventure

That hallmark of intellectual intensity is thanks in large part to the Honors Program.

Whether you took Honors or not, Swarthmore’s Honors Program had an enormous impact on liberal arts education across the country and contributed to creating what is quintessentially Swarthmore.

Before Honors: “Conventional and Undistinguished”

Yes, as surprising as it sounds, Swarthmore was an academically mediocre school. But it had potential. The Quaker Board of Managers was open-minded, and the College was financially sound. Aydelotte decided Swarthmore would be the perfect place to test a new American experiment in education: Honors.

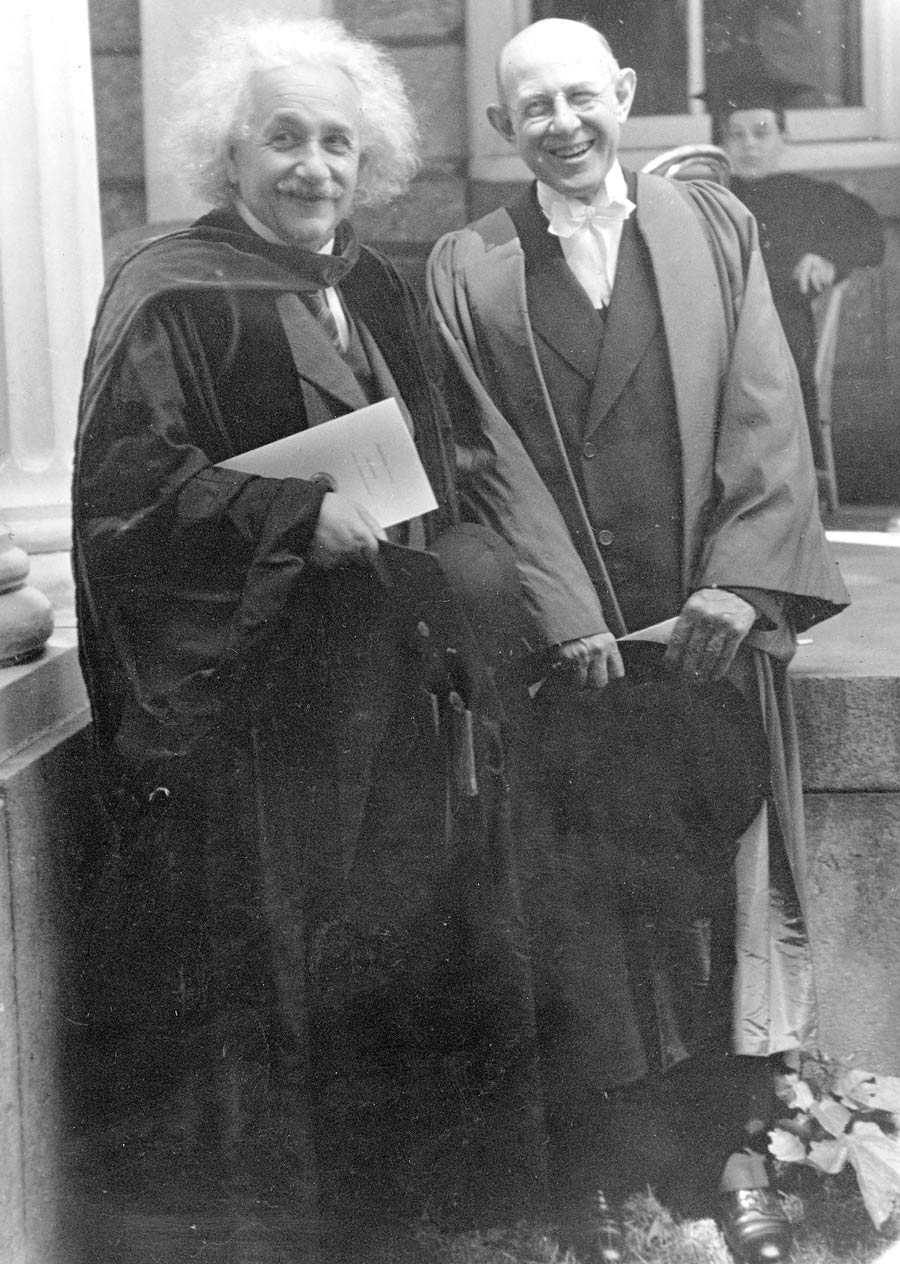

Aydelotte Introduces Honors in 1922: Oxford-inspired, with an American Twist

What he wanted to offer instead was intellectual rigor and freedom of study, a place where students would be challenged and live up to their potential. “The academic system as ordinarily administered is, for these better and more ambitious students, a kind of lockstep: It holds them back, wastes their time, and blunts their interests by submitting them to exercises they do not need,” stated Aydelotte.

He wanted what he’d experienced at the University of Oxford in England where he studied for two years (1905-1907) as a Rhodes Scholar and encountered the centuries-old tutorial system.

At Oxford, students met one-on-one with a tutor. Sometimes there were small groups of two or three, but the focus was always intense and individual. Students wrote weekly essays and explored ideas and opinions in energetic debates. There was no grading and students were free to exchange ideas supported by a mentor in a stirring atmosphere.

Sean Decatur ’90, college and museum president

How did Honors affect your life and career?

Honors offered an opportunity to participate in an intellectual community, with more responsibility not only for my own learning, but also a commitment to my classmates, since we shared the work of leading seminar discussions each week. This has become a model for my own teaching (right down to the shared rotation of seminar break snack duty).

How intense was it?

I still have a stress dream about my oral exam: I’m standing alone at a chalkboard, working through mechanisms of reactions I had not seen before, under the judgmental eye of an external examiner who was “chemistry-famous” for having written seminal papers in the field. In my actual oral for inorganic chemistry, I remember being asked to comment on how I’d approach extracting gold from ore mined in the far northern territories of Russia. I stood in awkward silence for what seemed like an eternity, before the examiner took me off the hook (“perhaps you have not studied this in your classes”).

Sean Decatur is the incoming president of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He was president of Kenyon College for nine years, and a lifelong champion for the liberal arts and a leading voice in the national conversation about higher education. He also served as professor of chemistry at Mount Holyoke, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Oberlin, and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Oberlin. He was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2017 and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2019. He was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2017 and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2019.

But would this work at Swarthmore?

Aydelotte decided to introduce a similar level of intellectual independence and mentorship. He did not set out to duplicate the British system. Honors would be Oxford-inspired, with an American twist. Instead of one-on-one tutorials, small seminars would be held. He added external examiners to change the dynamic between professor and student, so the focus became the subject, not the teacher.

“The two become allies in meeting an ordeal which is to some extent a test of both,” Aydelotte wrote. He thought students ought to “study subjects rather than merely to take courses, to lay emphasis upon thought rather than upon information, which is, after all, the secret of education.”

By 1922, the first Honors seminars had begun. “A decidedly new and progressive addition to the Swarthmore curriculum,” reported the student newspaper The Phoenix. The first year attracted 11 Honors students. Four years later, there were 72. In the next few decades, approximately 30-35% of students chose Honors. Its popularity exceeded even Aydelotte’s expectations.

Hallmarks of Honors

Seminars lie at the heart of the program. Instead of four a semester, Honors students typically take one or two in-depth seminars. Seminar size is small, often capped at eight or 10 students, with weekly papers and presentations by each member. Seminars are filled with vigorous debate and deep collaboration between professor and students. Honors takes place during junior and senior year. At the end of two years, outside examiners from other institutions evaluate Honors students through written and oral exams.

“It’s a unique capstone experience for the end of your college career,” says Ledbetter. “It’s a lot more education in a very short time. It’s like getting an extra year’s education at the end of your senior year, because you grow so much from it. It’s extremely high-impact teaching.”

And it’s intense.

“It’s incredible, intense immersion in a field, akin to being in graduate school,” says Tara Zahra ’98, a professor of East European history at the University of Chicago and a MacArthur Fellow. “It’s mastery of an entire subject and making connections between fields.”

Zoé Whitley Richmond ’01, art curator

How did Honors affect your life and career?

Art History Honors at Swarthmore is the genuine starting point of my curatorial career. Honors taught me to look closely, to ask questions, and to be unafraid to draw my own conclusions.

How intense was it?

Honors was intense, but the intensity came from the steep learning curve required to become self-directed. Swarthmore is like nowhere else, to be surrounded by inspiring, empathetic people who understand and accept that inner drive.

Zoé Whitley Richmond is an American art curator who lives and works in London. She is director of the Chisenhale Gallery, and past curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tate Britain, Tate Modern, and Hayward Gallery. She serves on the London Mayor’s Commission on Diversity in the Public Realm and is a trustee of the Teiger Foundation.

“For Phil Weinstein’s Modernism seminar, we read more than a thousand pages of Proust in three weeks,” says Batten, an assistant professor of English literature at the University of Pennsylvania. “We tackled all of Ulysses in the same amount of time, immediately afterwards … [I was] devouring books out of a combination of enthusiasm, nervous intensity, and sheer necessity.”

Preparing for outside examiners typically puts Honors students into a frenzy of study. They’re expected to synthesize all the concepts and material of their last two years. The exams can be grueling — and exhilarating.

“It gives you all the confidence in the world to feel you can speak on a topic in a coherent and intelligent way,” says Wood. “Students are often surprised by how easy and graceful it is,” says Craig Williamson, professor of English literature, and former director of the program. “This is a dialogue! If you can get your exam to feel like two people talking about matters that are interesting to them both, you forget that it’s an Honors exam. Then it’s working perfectly.”

Mythbusting Honors

MYTH: “It’s really only for Humanities students.”

Many science departments, including biology, chemistry, and physics have robust Honors programs.

MYTH: “It’s just for people pursuing careers in academia.”

Honors alumni go into a range of fields, including journalism, the arts, law, medicine, and business. Professors are actually a minority. No matter what the field, alumni often credit Honors as the defining point in their lives.

MYTH: “It’s not flexible.”

With only four seminars, there’s plenty of time to fit in other coursework. Honors preparations aren’t limited to seminars; students can choreograph a dance or write a thesis — there’s no limit.

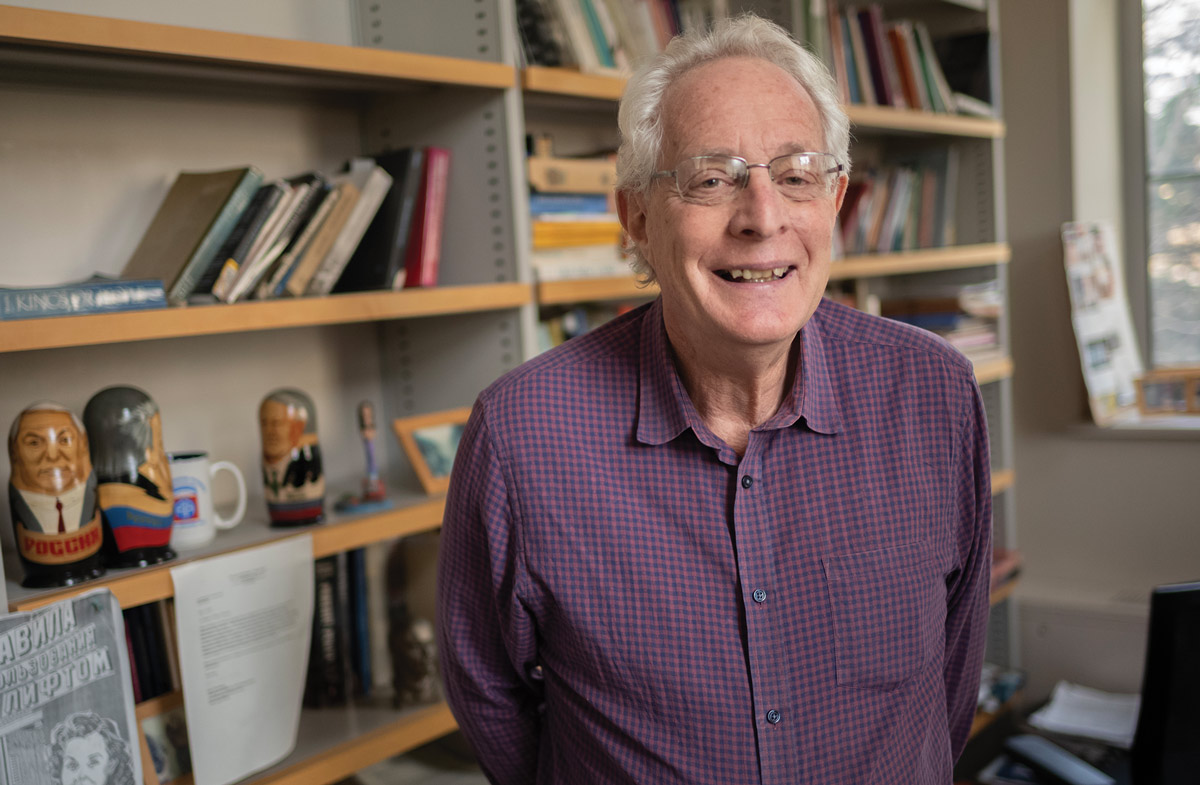

Tara Zahra ’98, professor

How did Honors affect your life and career?

It definitely changed my life. I didn’t see myself as an academic. I had no intention of going on to a Ph.D. in history before I took a seminar on fascism with Pieter Judson ’78 in the spring semester of my senior year. Now Pieter and I are working on a book together. The intellectual legacy of that seminar is pretty extraordinary.

How intense was it?

It’s incredible, intense immersion in a field, akin to being in graduate school. It’s mastery of an entire subject and making connections between fields. But we had fun, too, and formed very close bonds. We did lots of pranks and high jinks, and there were very elaborate snack breaks. One time someone brought in turnips to celebrate Turnip Winter in Germany and once a student made a cake in the shape of the Reichstag and set it aflame. That was legendary.

Tara Zahra is Homer J. Livingston Professor of East European history at the University of Chicago, and the Roman Family Director of the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society. A 2014 MacArthur Fellow, Zahra is the author of several books about globalization, nationalism, migration, and impacts of war on children and families. Her most recent book, Against the World: Anti-Globalism and Mass Politics Between the World Wars, will be published by W.W. Norton Press in 2023. She has served as an Honors examiner.

Honors Traditions

“We had a lot of pranks and high jinks,” recalls Zahra. “You form a very close bond. It’s a social experience as well as an intellectual experience.” Batten describes the delight felt by simply being in seminars with kindred spirits.

“Snack break conversation was unparalleled: We sat on the floor of Nora’s [Professor of English Literature Nora Johnson] classroom in LPAC eating chips and yelling about Macbeth, or on Phil’s [Phil Weinstein] living room couch complaining about Kierkegaard. … There was so much value to the enthusiasm and the joy.”

Seminars often last three to four hours, and can go longer when everyone is keyed up and engaged. “You forget time,” says Williamson. “You forget you’re the teacher. You become part of the intellectual quest.” He quotes Chaucer: “Gladly would he learn and gladly teach.” At the end of term, professors typically host a seminar dinner.

The vision and voyage of Honors

The vision and voyage of Honors

Another highlight is when the 100 examiners arrive on campus in May. Professors enjoy the chance to host colleagues and exchange ideas.

“Usually they stay in my house and they come down for breakfast in their pajamas and we talk about Beowulf,” says Williamson, one of the hosts.

“It’s a wonderful professional exchange,” agrees Ledbetter, explaining that the examiners themselves become ambassadors for the College. “They always rave about the program. ‘I can’t believe you do this! I want my kid to go to Swarthmore.’”

Caroline Batten ’14, professor

How did Honors affect your life and career?

Honors was the first time I was asked to be a scholar, rather than a student, to engage with texts on a higher intellectual level than had ever been asked of me before … and to contribute something entirely original in my essays to an ongoing academic conversation. [It] was the first time I understood that scholarship was a conversation, spanning time periods and geographies.

How intense was it?

Very. I read at brunch in Sharples, in McCabe until 2 in the morning, in Sci Commons draped across one of those red armchairs eating sushi … in every Adirondack chair on Parrish Beach. I studied harder for those exams than I’ve ever studied for anything, and was so hyper-focused for the three hours they each took that I walked into the doorframe on my way out of one; it was like surfacing from the bottom of the ocean.

Caroline Batten ’14 is assistant professor of English literature at the University of Pennsylvania. They are a scholar of Old English and Old Norse, and affiliated faculty in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies. They received their doctorate from the University of Oxford and were previously a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Iceland.

The Honors Influence

“The culture of the seminar has really carried over to the whole College,” says Ledbetter. “Honors is what started it, and continues to give Swarthmore a reputation for intellectual rigor which eventually caught on to the whole school. It’s not just small classes, it’s the idea of independent work. Swarthmore has a reputation for very active learners.”

When Aydelotte created Honors, other colleges were watching. “The experiment is one of more than local importance,” wrote Aydelotte, who published prolifically about education.

Why is it called Honors?

Christopher Bourne ’17, Ph.D. student

How did honors affect your life and career?

Entering Swarthmore, I knew I wanted to be a biology researcher. The Honors program simulated a Ph.D. experience. Through the Honors program, I read primary research literature to inform experiments for my scientific project. This is the exact same curriculum as a Ph.D. program. In fact, I was fortunate to publish the results of my Honors thesis.

How intense was it?

The Honors Program felt less intense than the traditional coursework. Single-credit classes at Swarthmore rely heavily on external homework. In the Honors program, the main focus was research progress. Rather than having a high workload to complete for a course, I had extra allotted time to do research. The flexibility of the Honors program allowed me to work hard on my research project when I had the time, but take small breaks to focus on other classes when necessary.

Chris Bourne is a 6th-year Ph.D. candidate at Weill Cornell Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, and an incoming postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on how cancer immunotherapy can be combined with small-molecule chemotherapies. Bourne is also co-director of sponsorships and partnerships for Black in Cancer, a nonprofit project that focuses on Black representation in cancer research and Black cancer health.

At 100, Honors is now more flexible and open. It’s no longer reserved for the higest-acheiving students. Honors offers students a unique capstone to their Swarthmore years, and promotes confidence and leadership.

Honors Reforms

Sidetracked by Love

Jed Rakoff ’64 H ’03 federal judge

How did Honors affect your life and career?

It was a very rigorous intellectual experience, and one that has stood me in good stead in my job as a federal judge. What it taught me was that sound answers to difficult questions cannot be answered quickly or intuitively, but require a lot of hard study and reflection.

How intense was it?

As final Honors exams loomed, I was modestly confident I would do well. But then, a few months before exams, I embarked on a tempestuous love affair (made all the more romantic by Swarthmore in the spring), and I completely stopped studying. Although as a result I flunked my Honors exams, I learned a lot about the intensity of human emotions that has also stood me in good stead.

Jed Rakoff ’64 has served as a judge for the U.S. Southern District of New York since 1996. He frequently sits by designation on the 2nd and 9th U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals and is an adjunct professor at Columbia Law School and NYU Law School. A prolific writer, Rakoff is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books, and most recently the author of Why the Innocent Plead Guilty and The Guilty Go Free, and Other Paradoxes of Our Broken Legal System (2021, Farrar Straus & Giroux).

These changes contribute to the robust and flexible nature of the program. Students still were required to declare a major and a minor, preserving Honors’ interdisciplinary nature and encouraging students to draw connections between fields. Enrollment shot back up to 30% again. “The ‘Reform to Four’ was really good,” says Zahra. “It made [Honors] more accessible and more compatible with study abroad or writing a thesis.” Notably, Honors students received grades. Why? Graduate schools were demanding it.

“No grades is a great system,” laments Ledbetter. “It allows for more learning. It allows you to make mistakes. But we have to compromise with the way the world is.”

Celebrating 100 Years

Swarthmore today is a far cry from the culture of 1922. No one calls it a mediocre school anymore. Honors has left its stamp on the entire academic nature of the College, offering every student an intellectual challenge. Today, Swarthmore is Swarthmore because of 100 years of Honors.