Designed to Succeed

Art and sport meld with beautiful results

by Sherry L. Howard

photos by Laurence Kesterson

Designed to Succeed

Art and sport meld with beautiful results

Designed to Succeed

Art and sport meld with beautiful results

by Sherry L. Howard

photos by Laurence Kesterson

The sport quickly became the center of Gal’s life. As a teenager, he traveled across New York and the Northeast for matches and played with the New York Red Bulls Academy team.

Recruited to play soccer at Swarthmore, he felt at home on the team. And when he received a Eugene Lang Opportunity Scholarship in 2018, Gal committed to finding new ways to share his love of the game.

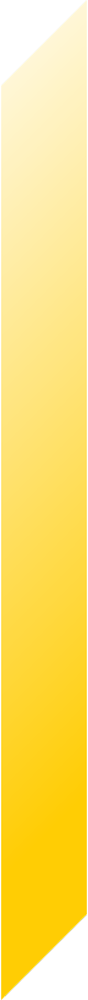

Eventually, he launched Design FC, an after-school program that works with youth to encourage creative thinking and autobiographical storytelling through the design of athletic jerseys and apparel. The program is based primarily at Stetser Elementary School in Chester, Pa.

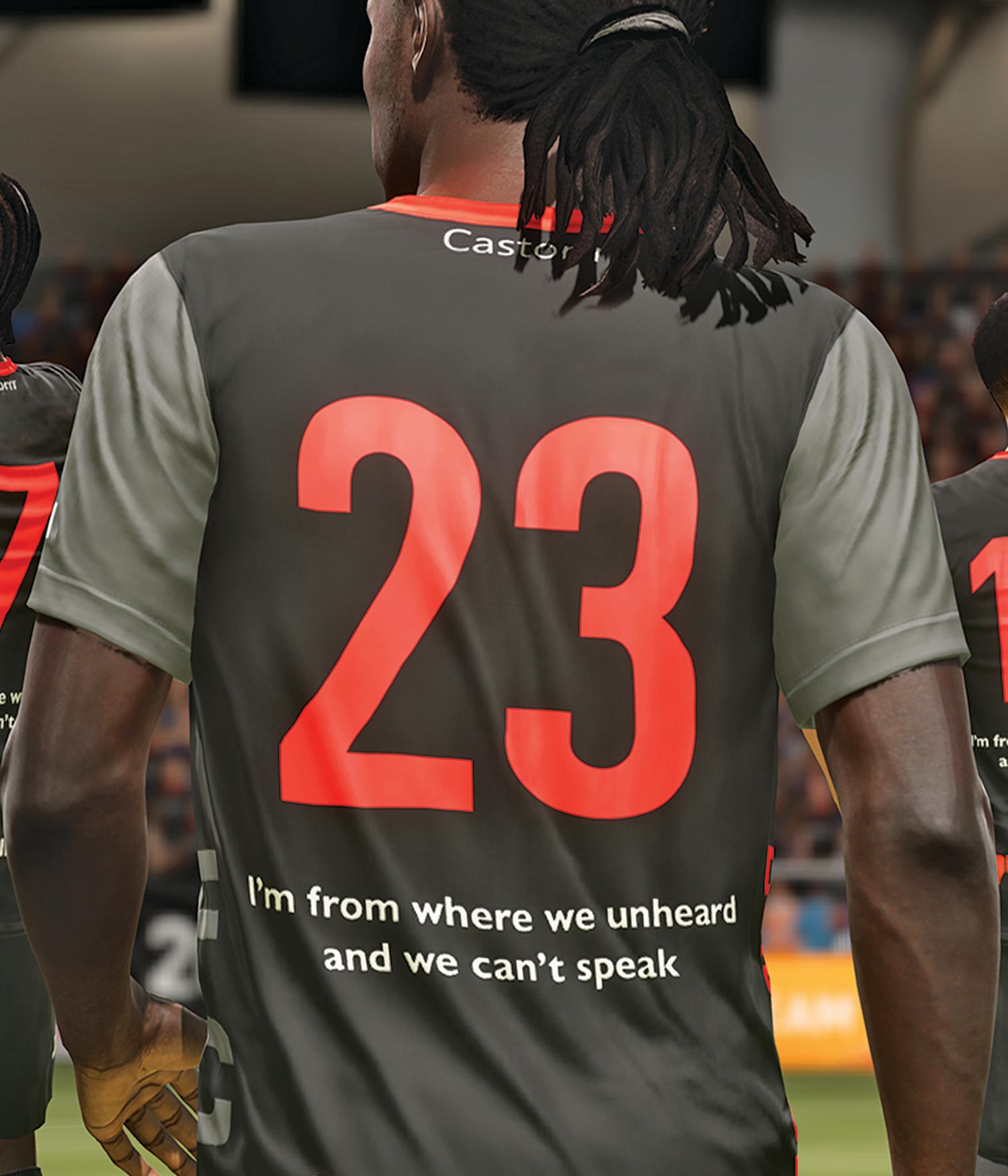

“It’s all about storytelling and self-expression and giving students a platform and medium to tell their stories,” says Gal. “These jerseys have become a blank template, a blank canvas, for them to speak about the things that mean the most to them or the things they want to change in the world.”

Over the past four years, DFC has collaborated with Major League Soccer and EA Sports FIFA — which led two DFC students to design jerseys for EA’s top-rated soccer video game. Brooklyn Nets star Kevin Durant’s charity foundation is a partner and supporter of DFC.

After Gal first met the students at Stetser, he recruited his then-soccer teammate Ayo George ’22. Two years after the program began, Oliver Steinglass ’20 and others at Swarthmore joined. The plan was to help guide the fifth and sixth graders in designing traditional jerseys. Initially, Gal imagined students creating jerseys that followed the typical designs of a sport jersey — a crest, name, and number.

But the students had their own notions of what their jerseys should be, says Gal. They would not be conventional. They nudged him to rewrite the curriculum he had so carefully constructed with design-thinking modules and problem-solving methodology and decidedly rewrote the rules.

“I realized at that moment we really needed to erase any previous notion of what a jersey is supposed to look like,” says Gal. “They became incredibly powerful pieces of art, and we’ve built on that since year one. It has grown from an after-school program to a nonprofit.”

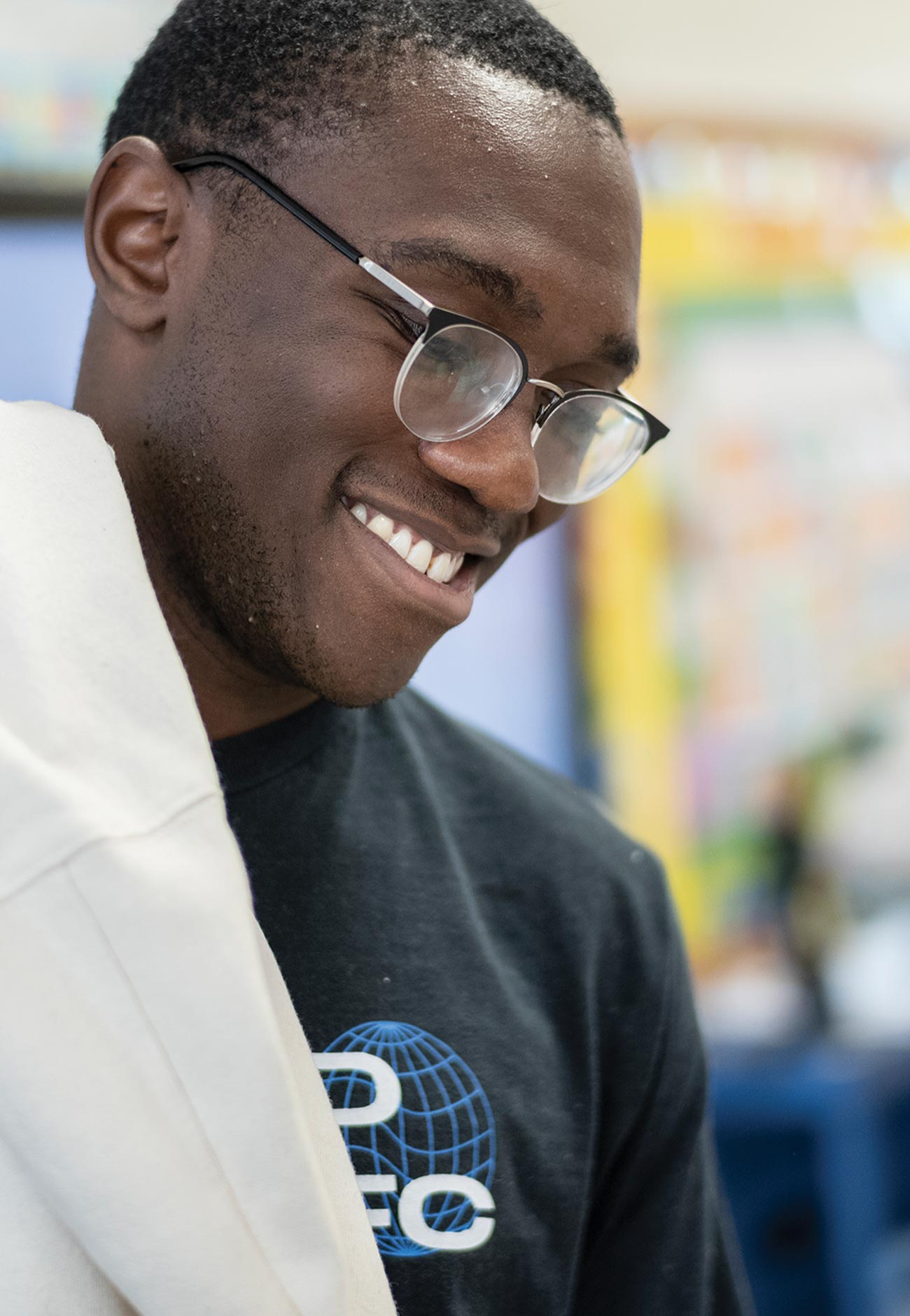

The students transformed the jerseys into art covering such issues as gun violence, police brutality, personal struggles, and mental health. They also articulated what they love most about themselves, offered thanks to their families, showed appreciation for their friends, and paid homage to the people they admire.

“My two big passions are art and soccer and to be able to connect the two of them is really fun for me,” says Steinglass. “To be able to work with kids in design projects and to have them related to soccer is sort of a dream.”

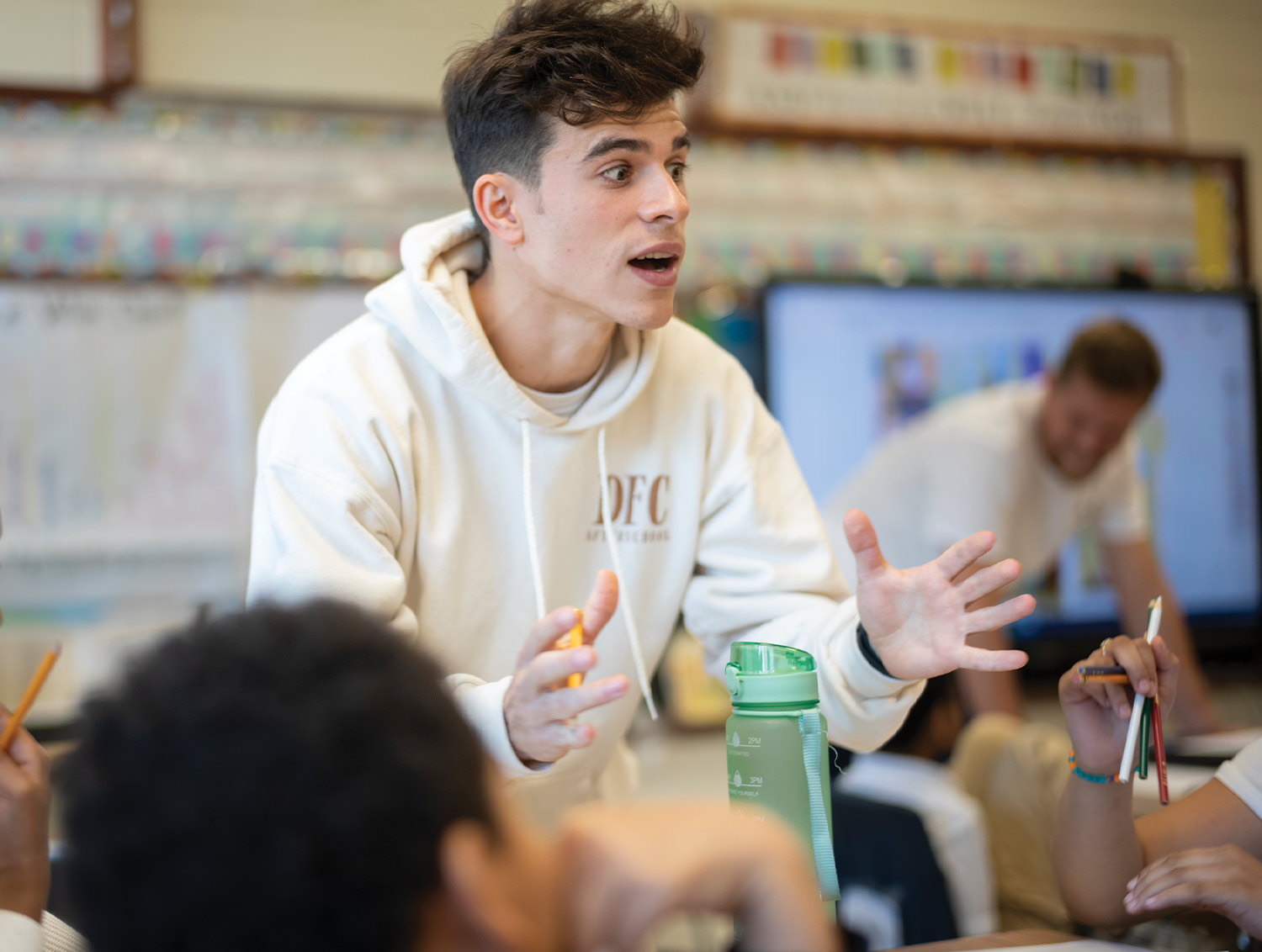

Two of those students, Kevin Stanford and Nyrell Hackett, have become standard-bearers for the program.

In 2021, their jerseys were featured in EA Sports’ FIFA 21 Ultimate Team, a popular video game played by millions worldwide. The two students have vastly changed DFC’s direction from what Gal had in mind in 2018 when he formed it with $10,000 in Lang Opportunity Scholarship funds.

“They’ve really pushed the program to grow and pushed us to provide them with new opportunities and new challenges,” says George. “I think they’ve been trailblazers for the next generations of students.”

—Denise Crossan, director of community and strategic initiatives

Getting started

“I knew I wanted to work with youth, and I wanted to involve soccer and sports,” Gal says. “But most importantly, Denise exposed me to the world of social entrepreneurship, and design-thinking, which helped inform the direction I wanted to take my project in.” He ultimately took a year off before his senior year to develop the DFC.

Building the Stetser Program

Steinglass, who came on board in 2020, was raised in a family of architects and painters. He grew up copying and designing soccer jerseys, stadiums, and crests as a boyhood pastime in Washington, D.C. He is DFC’s program director, as well as an assistant soccer coach at Swarthmore and an art teacher at the University City Arts League in Philadelphia. The Stetser students meet after school once a week for 22 weeks. The numbers dropped to about six during the pandemic when classes went virtual. Twenty students signed up for the sessions that started in October 2022. Over five years at Stetser, the program has served 70 students.

“That was the original intention,” Gal says. “What ended up happening was a bit different.”

The curriculum evolved with students designing jerseys that voiced their thoughts and feelings and projected social messages.

“I often found it had nothing to do with soccer,” says George. “It just happened to be on a soccer jersey. It’s really cool to see them push that definition and take ownership of it.”

The coaches provided the materials for the jerseys and manufactured them by hand. They volunteered their time, and sometimes, their own money. The program is now funded by donors whose contributions will carry it through the 2022-2023 school year.

DFC has plans to expand to the STEM Academy high school in Chester. The programming will focus on exposing seventh to ninth graders to different creative mediums and building design skills, says Gal. DFC has also conducted workshops in other cities, including public design projects in Los Angeles and Minneapolis in partnership with Major League Soccer for the MLS All-Star Game.

Gal says DFC wants to offer students access to mentorship, guidance, academic assistance, and exposure to career paths in creative fields along with access to technology and software to develop design skills.

Kevin and Nyrell epitomize what DFC wants the program to achieve, the mentors agreed.

“They have forced us to grow the program for them,” says George. The DFC team networked and created opportunities for the program. During the pandemic, they celebrated a collaboration with EA Sports for Kevin and Nyrell to design individual jerseys available to the 20 million players of FIFA 21. Kevin’s message was “I’m from where we unheard and we can’t speak” and Nyrell’s was “Stop the Violence.” The coaches arranged for EA Sports to notify them by letter that their designs would be used and their parents recorded them getting the news.

“Kevin’s reaction was one of the most amazing moments in my time working with Design FC,” says Gal. “Seeing him that happy and excited, it was a special, special, moment.”

“It’s cool for us also,” says Steinglass, “because as kids we grew up playing FIFA and I don’t think we ever thought we would be in it in any sort of way.”

These encounters show DFC participants potential careers in an industry where the pathway can be rocky, Gal says. African Americans like Kevin and Nyrell are not well-represented in the sports design business. (Black graphic designers make up 3% of the profession, according to fastcompany.com.)

“This is something we talk about a lot,” says Steinglass. “There’s a big gap. We’re working on our plan for the next four to five years and a big part of that is helping them in whatever way we can. [We want to] show them all these creative fields that exist and can exist for them if that’s what they want to do, and leverage the different connections and the different spaces we have been able to get into — whether it’s an internship or a college prep course.”

Earlier this year, the DFC team and Kevin and Nyrell were among speakers at the virtual Urban Soccer Foundation Symposium. Kevin and Nyrell have been accepted to the STEM Academy in Chester as ninth-graders. “Getting accepted into that school … is really more impactful than anything that we’ve done,” says Gal.

“Beyond all the design and FIFA,” adds Steinglass, “when we learned they’d both gotten into the high school, that was another really big moment for us.”