A Collection Revived

A Collection Revived

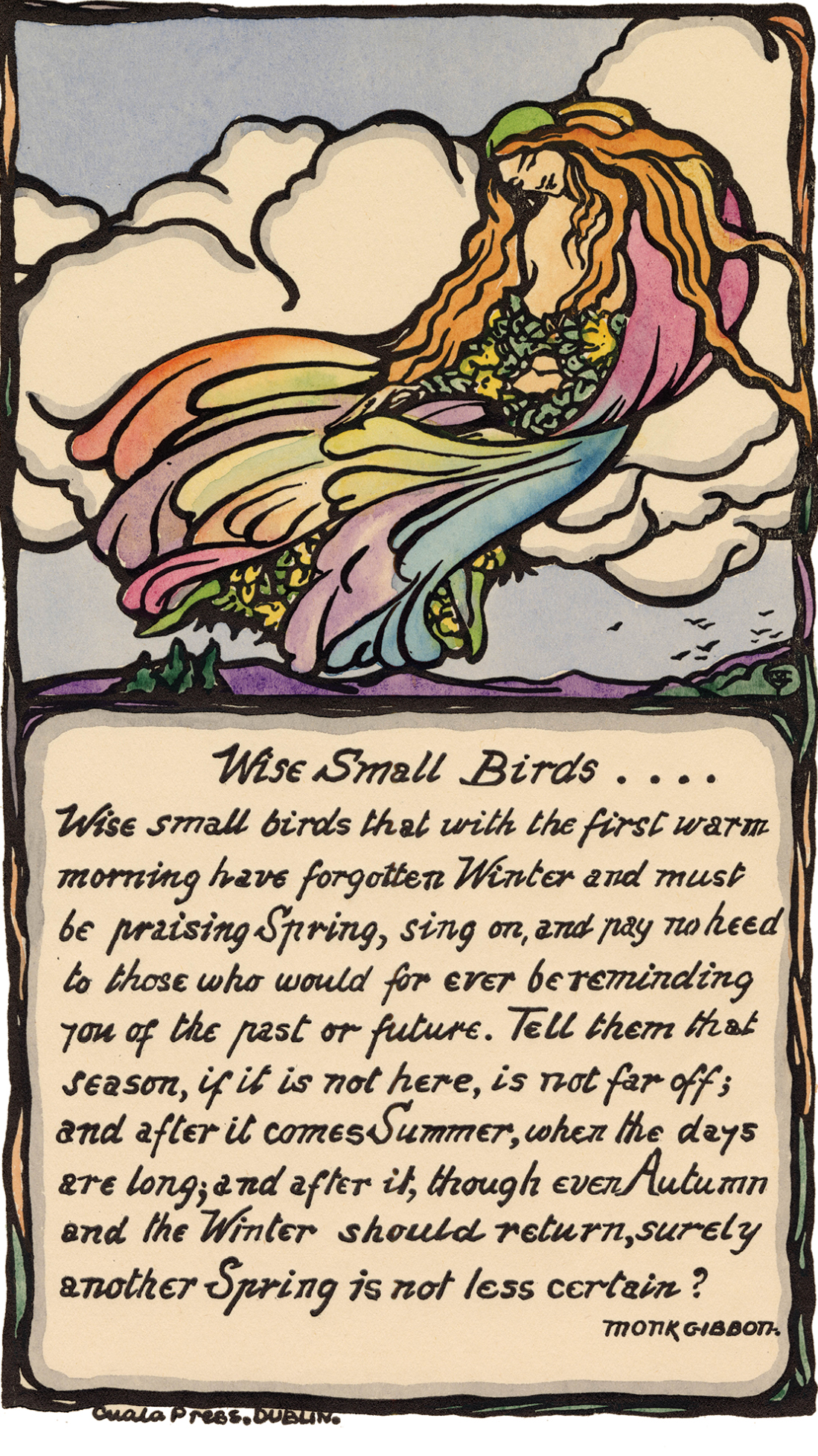

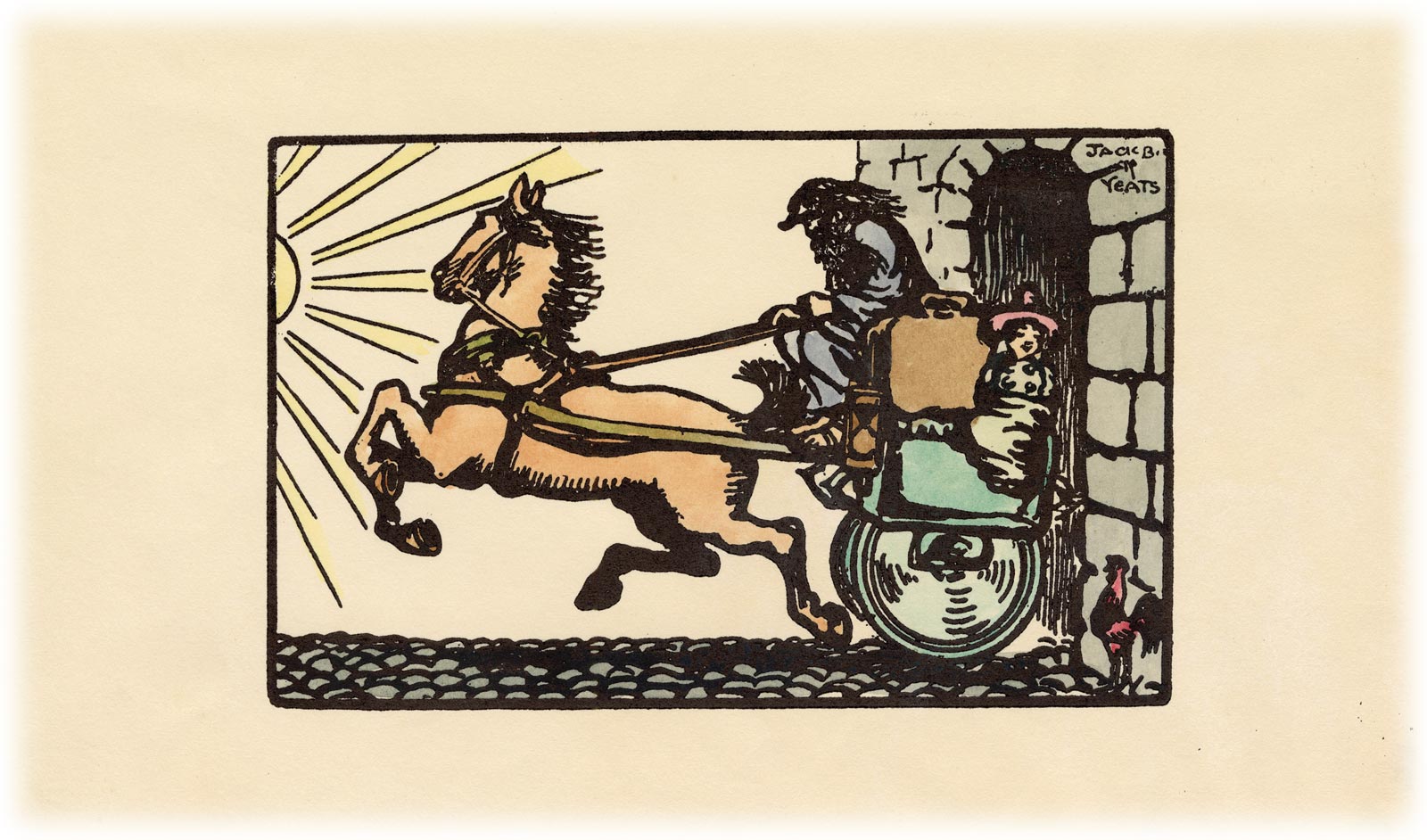

HEN KEVIN QUIGLEY ’74 and his wife, Susan Flaherty, donated their collection of Cuala Press prints to the College, they wanted to ensure the community could readily access the art. Their collection includes 73 hand-colored woodblock prints and broadsides created between 1906 and 1968 at the Cuala Press in Dublin. Originally called the Dun Emer Press, it was established by Elizabeth and Lily Yeats — sisters of poet William Butler Yeats — along with Evelyn Gleeson and Augustine Henry.

“A key criteria was to have it be accessible,” Quigley says. So he funded a paid student internship at McCabe Library to catalog and digitize the collection. “It’s really rewarding for me to hear there’s interest on campus,” says Quigley, “ I have a lot of confidence that Swarthmore will take good care of it.”

When Lemuel L’Oiseau ’25, whose pronouns are they/them, noticed a listing for the internship Quigley had funded, they quickly applied. L’Oiseau had spent the previous year working at McCabe’s circulation desk, nurturing an interest in the behind-the-scenes work of librarians — from cataloging and shelving to research and acquisitions.

L’Oiseau’s affinity for libraries began long before they arrived at Swarthmore.

“Ever since elementary school,” they say, “going to the library to check out a book was my favorite thing to do. Librarians had a major impact on me — they always knew the best book to recommend.” By the time they reached high school, L’Oiseau was working as a library proctor.

At Swarthmore, L’Oiseau is pursuing studies in computer science with a potential major in Chinese, and they’ve drawn connections between computer science and library science during their internship.

“There are so many things within the catologing realm of library science that are similar to computer science,” L’Oiseau says. “I’ve been able to apply what I’ve learned from my computer science courses to how I think about cataloging, and it’s been really cool to integrate my learning into an actual job.”

Influenced in part by this experience, L’Oiseau is considering a two-year library science program after graduating from Swarthmore. “I’m inspired to look beyond the typical resources of computer science,” L’Oiseau says.

Since the summer of 2022, L’Oiseau has worked with Metadata Management Librarian Katrina Jackson to digitize and catalog the 73 woodcut prints and broadsides from the Quigley’s collection, some of which date back to 1906.

L’Oiseau’s work will ultimately make these prints accessible and searchable to anyone worldwide, and Quigley hopes this work will help the collection become a resource for professors teaching and students studying 20th-century literature or Irish poetry.

In 1969, W.B. Yeats’ children, Michael and Anne Yeats, took up operations of Cuala Press. Five years later, after graduating from Swarthmore, Quigley arrived in Dublin to further his studies in Anglo-Irish literature. Living in Dublin, he immersed himself in Ireland’s literary and artistic milieu.

Though Quigley spent much of his time in the National Library, he would take his lunch breaks at Cuala Press down the street.

“I was there three or four times a week for most of the year,” Quigley says, “and they likely took pity on me as a graduate student — so they discounted the prints or simply gave me the final proofs for free.” For Quigley, the prints underscore the “inspiring power of the Celtic Renaissance and the remarkably talented Yeats family that contributed immeasurably to a rejuvenation of Irish arts and culture in the 20th century.”

For L’Oiseau, handling these century-old pieces was, at times, “surreal — you can see how intricate the printmaking process is, and how each piece has to be carved by hand.”

The Cuala Press prints’ evocative imagery — often inspired by esoterica, including the tarot — also captivated L’Oiseau. “There’s a recurring image of an old man holding an hourglass, and it stuck with me. As I was cataloging, I kept seeing it over and over again. It was intriguing to think about how the artists perhaps used the hourglass not just as a metaphor for the passage of time, but to show us how we’re all still here, and how we’re human.”

“I consider myself to be a creative person,” L’Oiseau says, “I knit, I crochet, and I cross-stitch. Sometimes, when I’m trying to figure out what I’m going to make next, I look back at vintage patterns.”

“These prints are kind of like that for me … looking back at art people have made in the past gives me momentum and inspiration,” says L’Oiseau. “Art can remind us of where we came from.”

the Art of woodblock printing

Mahayana Buddhists in China were among the earliest practitioners of woodblock printing, creating religious documents and talismanic objects dating back to A.D. 650. The method spread to Korea and Japan shortly thereafter, and by A.D. 1000 it was common across Eurasia.

During Japan’s Edo Period (1603–1867), woodblock printing saw a popular resurgence bolstered in part by Japan’s growing middle class and tourism industry. Easily produced, portable, and relatively inexpensive, woodblock art prints became popular items in bookstores and gift shops throughout Japan. An iconic and widely reproduced example of this period is Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa, first printed around 1831.

These prints had a tremendous influence on European artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly the Impressionists and Post Impressionists, and the artists of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements. For European artists, Japanese woodblock prints introduced new concepts of form and subject matter, including asymmetrical compositions, nontraditional poses, flat fields of color, and scenes of everyday life — characteristics found in Kevin Quigley ’74’s collection of Cuala Press prints.

—NICK FORREST ’08