a Mural

S artworks painted directly on the walls or ceilings of a building, murals symbolize permanence. When that building is demolished, the paintings vanish with it.

But not at Swarthmore.

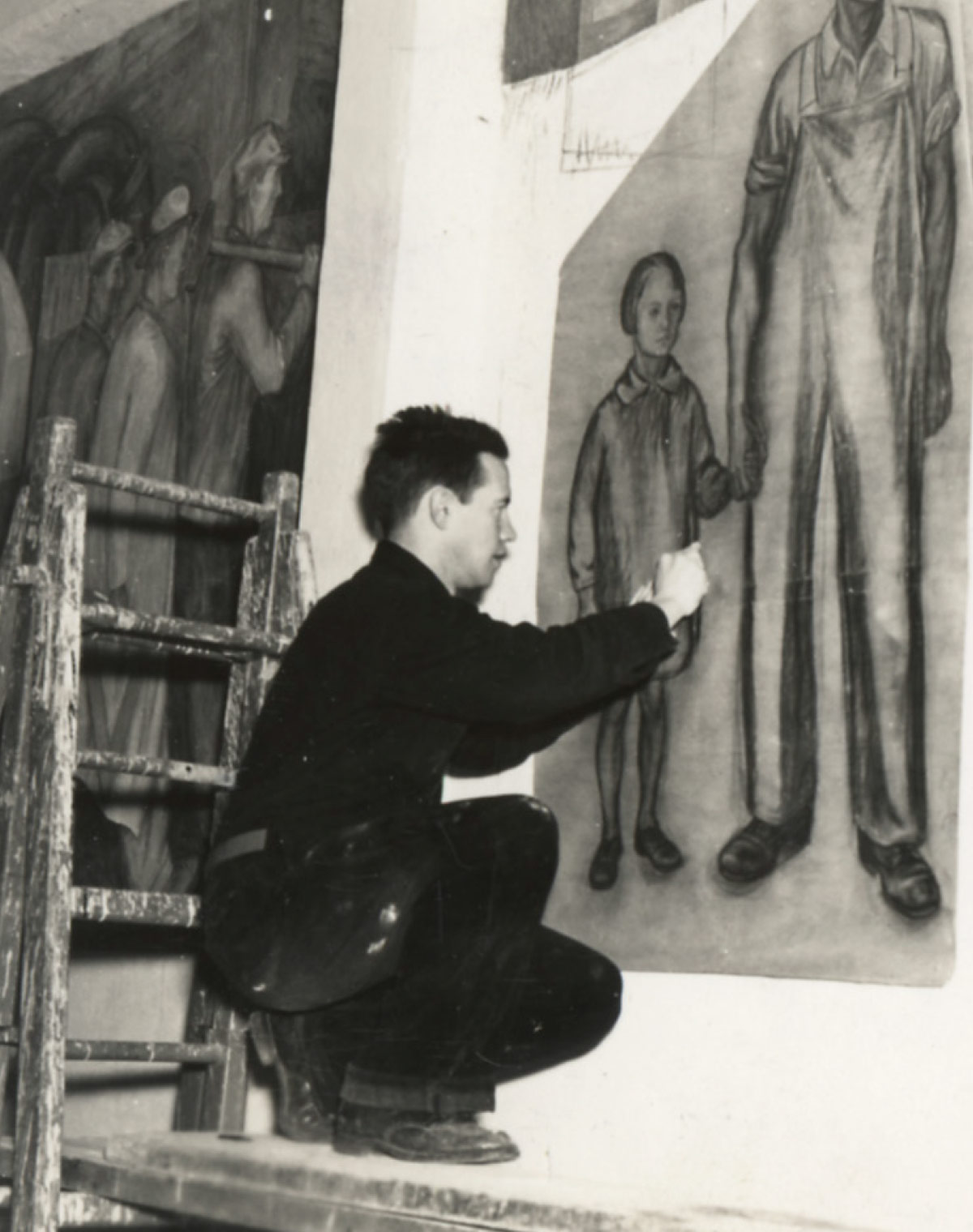

For 80 years, the unlikely location of the College’s most significant murals was a lecture room in Hicks Hall, until recently home to the Engineering Department. Painted in the late 1930s by James D. Egleson ’29, the frescoes’ theme was the interaction of science and society. Generations of students were distracted from lectures by scenes of heavily muscled men working intently on physical and mental tasks alongside those whose lives have been disrupted by unemployment or war. Images of a poverty-stricken woman and an aged-looking little girl appear, as do symbolic still lifes of bombs, handshakes, books, and tools.

By 2012, the Engineering Department needed more wall space and hid the murals under a removable covering. Selected views could still be seen behind small hinged openings called “truth doors,” says Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach.

a Mural

S artworks painted directly on the walls or ceilings of a building, murals symbolize permanence. When that building is demolished, the paintings vanish with it.

But not at Swarthmore.

For 80 years, the unlikely location of the College’s most significant murals was a lecture room in Hicks Hall, until recently home to the Engineering Department. Painted in the late 1930s by James D. Egleson ’29, the frescoes’ theme was the interaction of science and society. Generations of students were distracted from lectures by scenes of heavily muscled men working intently on physical and mental tasks alongside those whose lives have been disrupted by unemployment or war. Images of a poverty-stricken woman and an aged-looking little girl appear, as do symbolic still lifes of bombs, handshakes, books, and tools.

By 2012, the Engineering Department needed more wall space and hid the murals under a removable covering. Selected views could still be seen behind small hinged openings called “truth doors,” says Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach.

The search was on.

The committee concerned with the murals’ future consisted largely of art and art history faculty, under the stalwart leadership of Mari S. Michener Professor Emerita of Art History Constance Hungerford. The curator of the College’s art collection for four decades, she felt strongly that the murals should be saved “as both an exciting teaching resource and part of the College’s history,” one that was distinctive for including engineering at a small liberal arts college.

— Associate Professor of Art Logan Grider

Locating a company that could move murals was a project in itself. The committee, along with Susan Smythe, then senior project manager in the College’s Facilities Management office, discovered Materials Conservation LLC in late 2014. Based in Philadelphia, the company had recently moved a Maurice Sendak mural and understood Swarthmore’s challenges.

It was a happy collaboration.

“Even the company who supplied the scaffolding got really excited about it,” says Smythe. David Facenda, senior architectural conservator at Materials Conservation, oversaw the work, which involved detailed construction planning and close coordination with the College.

Those hurdles ranged from the delicate to the monumental, as the contractors took great care to keep the thin painted plaster intact while moving up to 1,400 pounds of dead weight supporting each wall section.

The murals had been painted in traditional buon fresco, applying pigment directly to wet plaster on the walls. This method was used by the Renaissance masters in which one day’s work in lime-based wet plaster, called giornata, was prepared daily.

A “cartoon,” or full-scale preparatory drawing on paper, was laid out on the wall; pinpricks or other incisions outlined the figures, and chalk dust was “pounced” in the paper’s holes to transfer the design onto the plaster surface.

Materials Conservation surveyed and documented the Hicks room. The company worked with the committee to determine which murals could be saved and where they would be placed in Old Tarble. After adjusting for some deterioration in a wall section, MC, in consultation with painting conservator Gwen Manthey and local structural engineer Melanie Rodbart, developed a detailed multistep removal plan for each chunk of wall. This involved creating bolted-together “sandwiches” of mural-covered wall sections and protective coverings.

During that time, Egleson decided “that the purpose of work and science should be to enhance human welfare,” and that art, too, should have the same objective. “The sense that they were making art for the people” was central to the Mexican muralists’ work, Egleson’s son Jan noted.

Egleson traveled to Mexico City and Guadalajara to train with Orozco from 1935 to 1936. Describing his father as “a lifelong lefty,” Jan said, “that’s where his radicalism began, in Mexico through … mural painting.” Orozco influenced a whole generation of young American artists, including Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock.

The Mexican muralists thus helped lay the foundation for the New Deal’s public art programs. Egleson himself was galvanized by his self-described “re-education.” He returned to America looking for “walls of my own to paint.” He found them at Swarthmore. At the time, there was scant permanent art at the College and studio art was not part of the curriculum, but he found a sympathetic ear in President Frank Aydelotte.

The murals opened to public acclaim during Commencement in 1938. Fine Arts Professor Alfred Brooks proudly noted, “It is as true today as of old that pictures on walls are the books of the people.”

Nearly 40 years later and not long before he died, Egleson returned to Hicks to repair the aging murals.

how exactly did they do that?

The murals were removed by August and spent their leave of absence in MC’s Philadelphia studio before being returned to Swarthmore in 2019. They arrived in their new Old Tarble home through a window opening, landing on scaffold that effectively added a second floor to the double-height studio space. The plaster was removed from mapped-out spots where the mural segments were to be positioned, and 8-by-8-by-1/2-inch shelf angles were installed in the stone walls. Then each mural segment was lifted and shimmed into place. The shelf angles were fastened to existing ones in the murals’ bottom edges, and the tops were secured with clips.

Thin frames covered the mural edges just enough to protect them and were painted to match the refinished plaster, making the images seem more like part of the wall. Paint conservation work was needed to rejoin sections of scenes that had been removed in pieces and also to repair bolt holes and some of the facings that suffered minor damage.

With the crew working only during College breaks, the job was finished by the 2019–20 winter holiday.

The whole long process, Hungerford says, “was quite a miracle.”

Hung high in Old Tarble’s dramatic, light-filled studio, the mostly life-size murals are highly visible while allowing for crucial artist pin-up space below.

They “have enlivened the space,” says Randall Exon, the Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot Professor of Art. “Now it feels like a museum walking in there.”

Exon says when they cropped down to these individual scenes, they started to see the value that they had in terms of composition and in the frame. How the parts related to the whole within the individual sections has been very helpful for teaching, he says.

When a student recently asked if linear perspective was the way to convey a sense of space, Exon responded that it was one way, but another way, which he could show in the murals, was through areas of overlap.

“All the principles and elements of design” can be taught from the murals, Grider says, including a few “things that don’t quite go well.”

And though the murals depict many difficult subjects, Grider sees a lot of “tenderness” in them, too. “These kinds of paintings give me hope,” he says. “This is a great example of what you can do in a building that also enriches the culture of the place and the teaching that goes on here.”

A small sample mural “sandwich” will be used in a conservation course taught by Associate Professor of Art History Patricia Reilly and James H. Hammons Professor of Chemistry Thomas Stephenson.

“It offers a wonderful opportunity for our students to see firsthand the structural nature of fresco painting,” says Reilly.

“I’m glad that the murals have found a new life that’s relevant to the old life in the College,” Hungerford says. “It continues so many of the concerns for the larger social-justice world in which we live, and the relationship of science to humanity.”

In this time of pandemic, their message could not be more apt.