Seeing

Under

Water

iologist Sönke Johnsen ’88 has had a glowing career. After all, he co-discovered the first bioluminescent octopus and even figured out how a frog can be invisible.

This Duke University oceanographer has seen it all. His specialty is vision in animals and biophysics — how they use such things as light, mirrored surfaces, or ultra-black color to attract a mate, find food, or hide themselves.

“Nature is this amazing family story,” says Johnsen. “The natural world is like War and Peace going on for four billion years.”

“There’s always another new animal evolving some completely new, strange way of doing things. It’s random, crazy, and funny, and that’s what kept me in my field — this endless story and its humor.”

While some biologists devote their careers to one species, Johnsen has studied more than two dozen, ranging from scallops, seals, and squid to spiders and the tiny northern glass frog (Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni) of Central and South America.

To learn how this leaf-hanging leaper pulls off its vanishing act, Johnsen created a small tropical rainforest in the basement of his science building at Duke. He found that the glass frog can suck 90 percent of its red blood cells into a mirrored pouch in its liver. Since its translucent skin reflects little light and its red-blood-cell-free blood cannot absorb light, the frog disappears and becomes safe from predators.

“A pretty good little trick,” says Johnsen of a discovery that, according to him, got “a ridiculous amount of press coverage.” Carlos Taboada, who is now an assistant professor of biology at Vanderbilt University, was a primary contributor to this work, he adds.

Lohman and Johnsen recently investigated how leatherback turtles make their 3,000-mile migration from Newfoundland to Trinidad.

“They are enormous — half the size of a VW Beetle,” says Johnsen. “We’ve had a great time puzzling out how they make the trip using the Earth’s magnetic field.”

“It was like we caught evolution in mid-step, which you don’t often see,” he recalls.

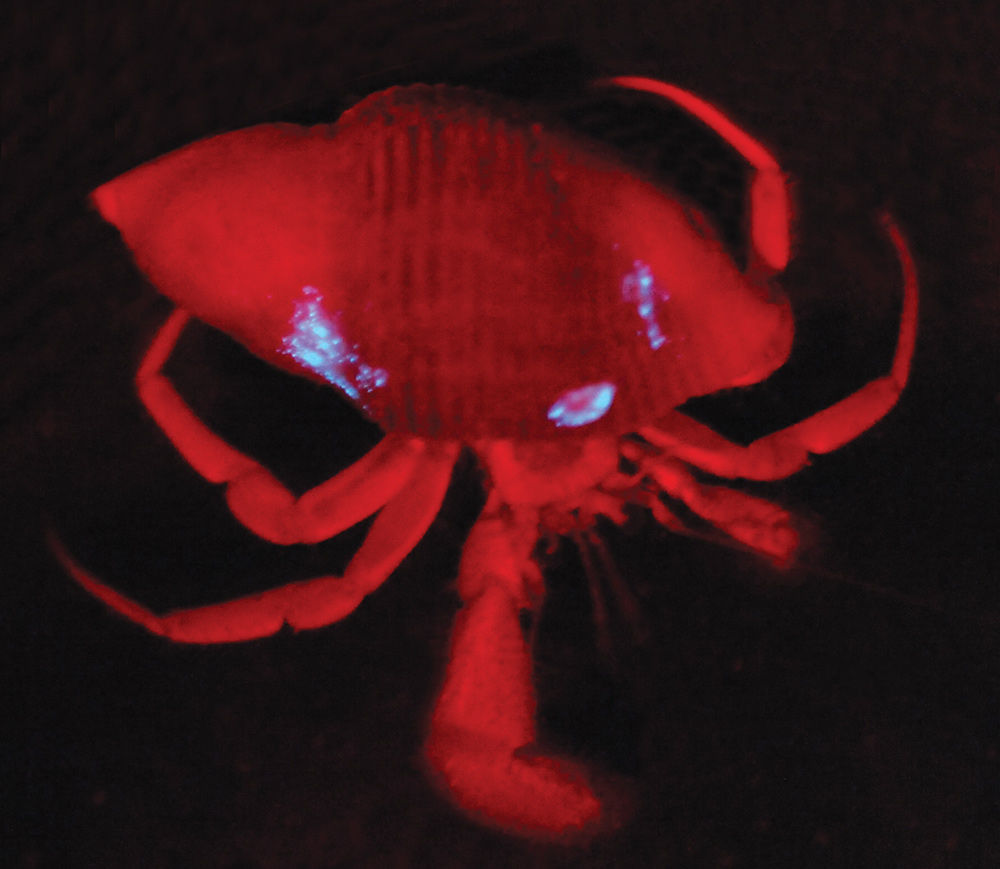

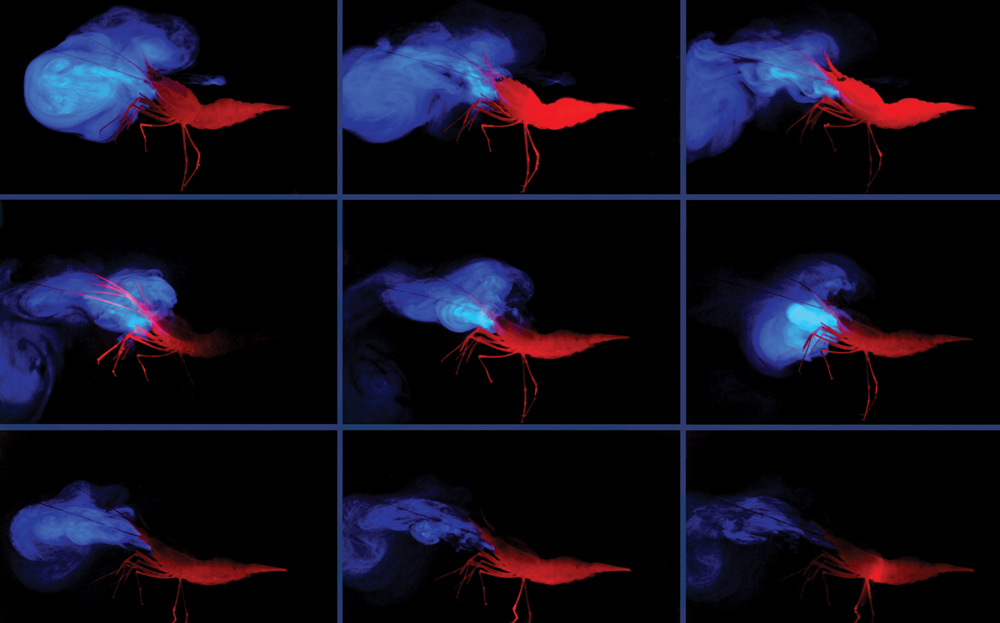

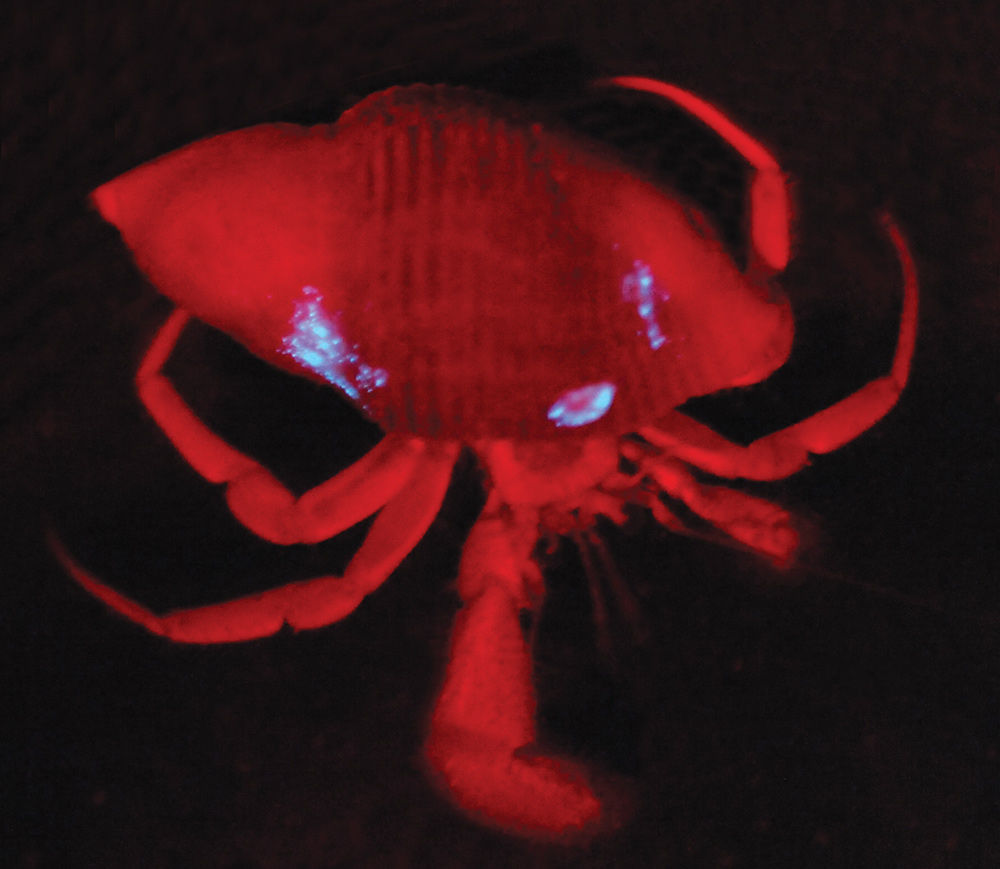

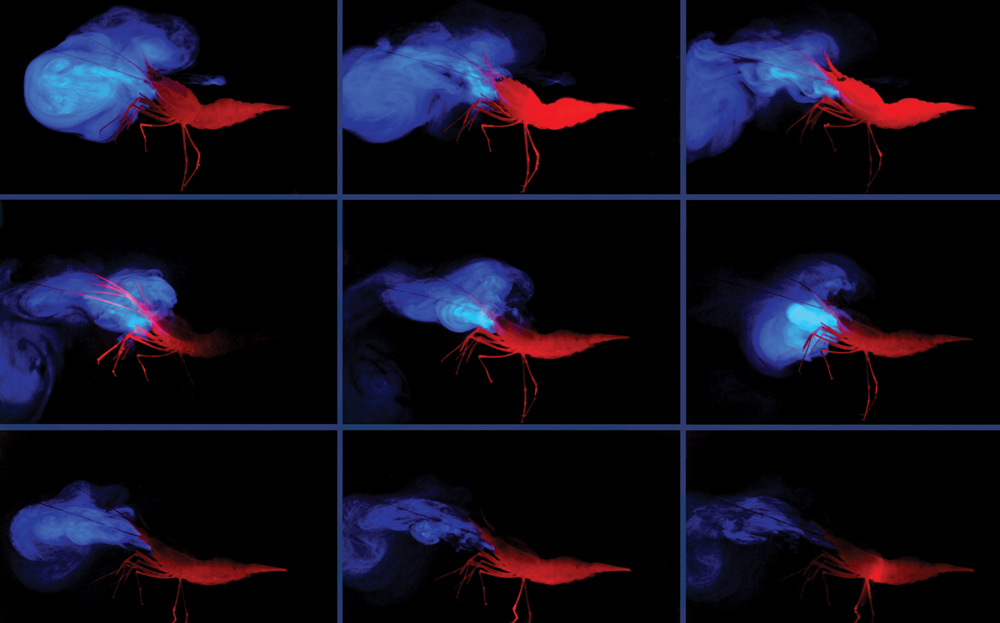

Widder and Johnsen concluded the suckers glimmered to lure prey, not to grab it. Their photograph of the neon creature caused a sensation and landed on the cover of Nature magazine. Today, Johnsen and Widder continue to collaborate.

“Sönke is always producing something new and exciting,” she says. “His outside-the-box thinking has transformed the field.”

“I’m really bad at thinking about myself in terms of achievements,” says Johnsen. “I do what I like and what I can to see the world in my own way.”

The latest feather in Johnsen’s scholarly cap is his admission to the Royal Physiographic Society of Lund, one of Sweden’s royal scientific societies. “I have to show up there in tails this December,” he says with a grin. What Johnsen doesn’t know humbles him. “Now and then, an animal does something that seems so impossible all I’m left with is the nagging concern we must be overlooking something big and important,” he writes in his recent book, Into the Great Wide Ocean: Life in the Least Known Habitat on Earth (Princeton University Press, 2024).

Smithsonian Magazine deemed it one of its Best Books of 2024. His next book, The Radiant Sea: Color and Light in the Underwater World, co-written with Steven Haddock (Abrams Books) comes out in September.

“He was somebody I always thought was going to go his own way and forge his own path,” Shapiro recalls. Meanwhile, Johnsen minored in art. He sculpted, painted, and designed sets for the campus theater group. “The art itself, the doing of it, got me fascinated with light, color, and vision,” he says. His motto is something attributed to the late New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra. “If life were perfect, it wouldn’t be.”

“I’m not sure he meant it this way,” says Johnsen, “but it reminds me that what makes life special is its imperfection.”