Boxed In

Building a crossword puzzle is akin to writing a poem: Just as the poet must be mindful of the elements of meter, assonance or dissonance, and often rhyme, so too must a crossword constructor consider how answers fit in an interlocking, interdependent grid and how the clues, filled with ambiguity, references, and wordplay, might be interpreted by the solver.

In the early 20th century, a “crossword craze” was sweeping the nation, and women were at the forefront. Housewives, suffragists, and flappers shaped the puzzle in its early days, and, as a result, it was labeled a feminine “distraction” from more “useful” intellectual pursuits.

Although the crossword remains highly popular today, its cultural associations have undergone a radical transformation. Solving The New York Times crossword confirms one’s status as a serious thinker, and published constructors are overwhelmingly male.

Anna Shechtman ’13 explains how this shift happened in her recent book, The Riddles of the Sphinx: Inheriting the Feminist History of the Crossword Puzzle (HarperCollins, 2024), in which she examines the history of puzzles through the women — editors, writers, and academics — who were central to their transformation into the cultural institution it is today.

Absorbed in the world of puzzles since high school, Shechtman, a New York City native, became one of the youngest female constructors ever published by The New York Times in 2010, while at Swarthmore. She worked with Times puzzle editor Will Shortz after graduation, and currently contributes crosswords to The New Yorker.

Her book examines the history and evolution of crosswords, but it is also a deeply personal memoir in which she examines the possible relationship between her fixation on writing puzzles and her fixation on becoming dangerously thin, both of which began around the age of 15.

“The twinned projects of trying to tame and control my body through anorexia and the body of language through crosswords were foolhardy at best and a huge preoccupation for many, many years of my life,” she says.

The Riddles of the Sphinx draws its title from a 1977 experimental film of the same name directed by Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey, who helped popularize the term “male gaze.” In it, Mulvey challenges viewers with 360-degree panning shots of traditional sites of women’s work, but women themselves are only ever shown in motion, passing in and out of focus.

“The film looks into women’s language, culture, and place in life, like being responsible for both child care and maintaining the house, and also emerging into the work world and into feminist politics in the 1970s,” says Centennial Chair and Professor of Film & Media Studies Patricia White, who did an independent study with Shechtman as a student and read her book as a manuscript.

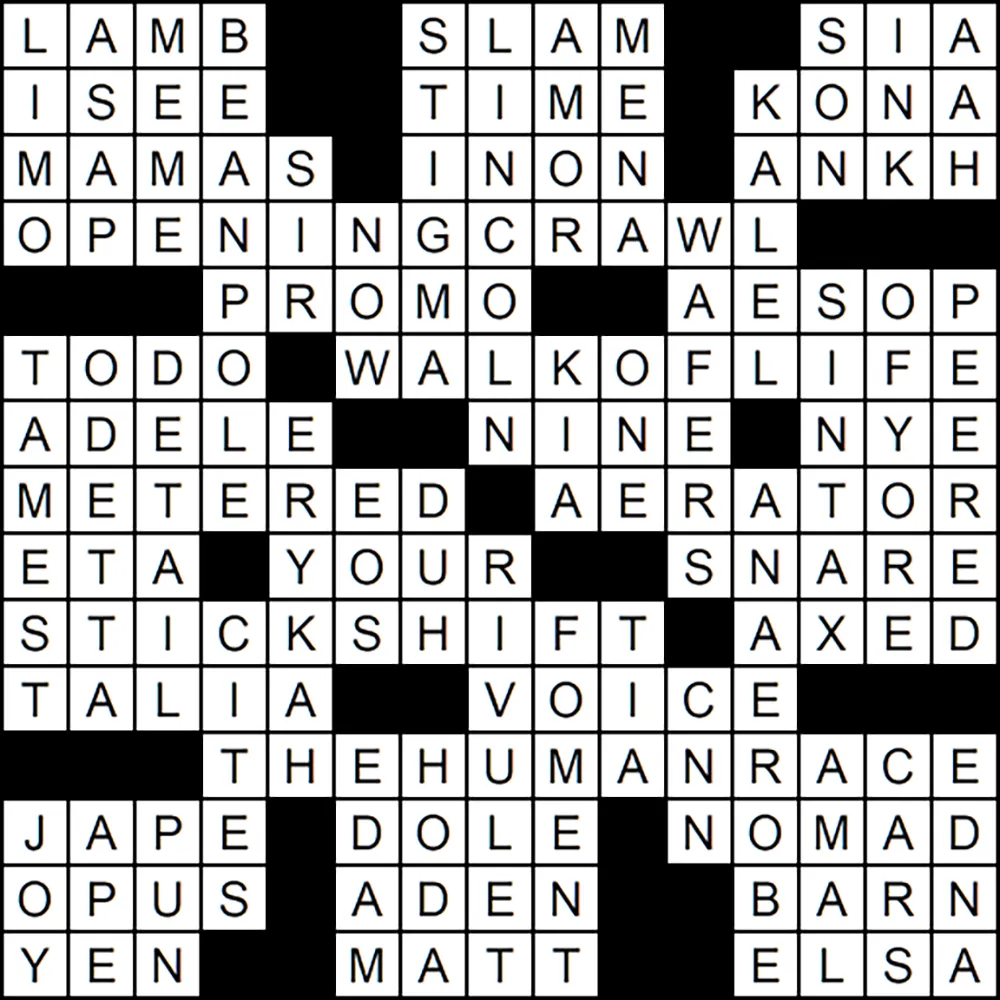

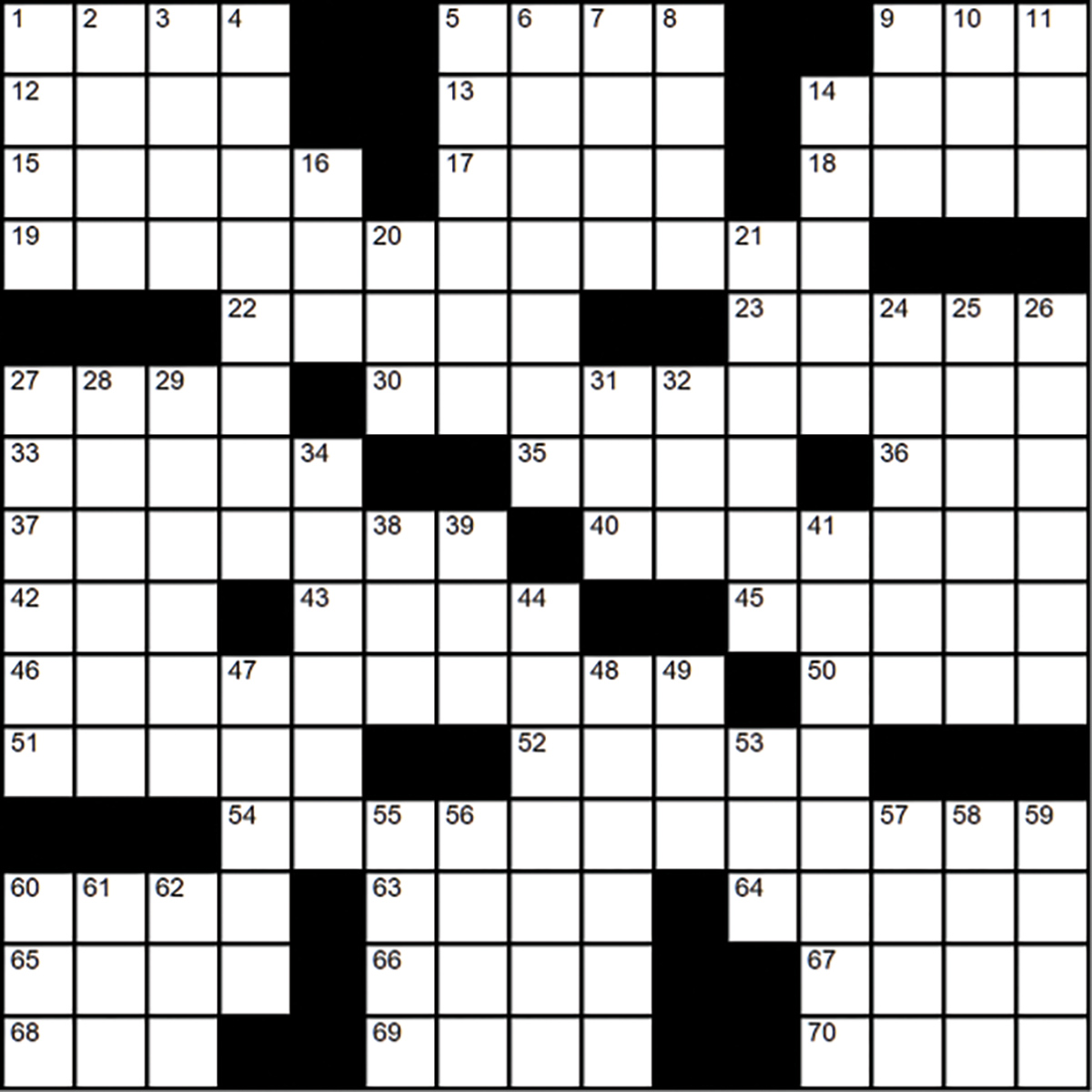

Leg Day Exercise

Fill in the crossword puzzle here to reveal Oedipus’ answer.

5. Poetry competition

9. Chandelier performer

12. Understood

13. The fourth dimension, possibly

14. Hawaiian coffee region

15. Half of a 1960s folk-rock group that sang about Swarthmore in Creeque Alley

17. Privy to

18. Egyptian key of life

19. Intro text for a Star Wars film … or the first part of the solution to the Sphinx’s riddle?

22. Teaser

23. Fabulous writer?

27. List heading

30. 1985 hit for Dire Straits … or the second part of the solution to the Sphinx’s riddle?

33. Artist whose album titles are age-appropriate?

35. Number of muses in Greek myth

36. December 31, for short

37. Measured

40. Wine accessory

42. GPS approximation

43. Part of B.Y.O.B.

45. Drum kit essential

46. Manual transmission … or the third part of the solution to the Sphinx’s riddle?

50. Fired

51. Shire in Hollywood

52. Tenor or soprano

54. Group that engages in 19-, 30-, and 46-Across … and the final solution to the Sphinx’s riddle?

60. Practical joke

63. Produce giant headquartered in Dublin

64. Wanderer

65. Great work

66. Port of Yemen

67. Home for a farm team

68. Japanese bread?

69. Damon of the silver screen

70. Frozen queen

2. Posthaste

3. Shared and remixed Internet joke

4. Growing support for a green party?

5. Scarlet letter, for example

6. Mary Todd _____

7. Latin love

8. Actress Suvari

9. Oedipus, to Jocasta

10. Body art, informally

11. “That feels amazing!”

14. Given name of Superman

16. ___ Duke (1977 Stevie Wonder hit)

20. Feminist group founded in 1966, briefly

21. Communion offerings

24. Price for a vice

25. In olden days

26. Looked (in)

27. Least controversial

28. Legendary headliner of the 1958 Swarthmore Folk Festival

29. Specific part of a plan

31. Company selling Souls

32. Opening number?

34. Singer Badu

38. Dawn goddess

39. “Obviously … ”

41. Organism that doesn’t need oxygen

44. Small stream

47. References in a footnote

48. Whip up, as a revolt

49. Madre’s hermana

53. Situation Room channel

55. Cheese that’s made in reverse?

56. Morning TV host Kotb

57. Human rights lawyer Clooney

58. Mustangs and Beetles, for example

59. Teacher Krabappel on The Simpsons

60. Amy Poehler’s character in Inside Out

61. Mimic

62. Punchline for a groan-inducing joke, often

The rise of computers is another unexpected potential explanation for this decline, Shechtman says, mainly in the form of crossword-building software capable of combing through thousands of potential answer possibilities and filling out a grid in mere seconds.

In a chapter titled “When Computers Replaced Women” Shechtman, who constructed puzzles by hand until 2016, explores how early computing was done by women, who were viewed as being more suited to the “painstaking, tedious work requiring patience and dexterity of the hands.”

Over time, as computers became more sophisticated and efficient, tech culture became increasingly masculinized, causing a gender imbalance that permeated the world of crossword constructing.

“Both [programming and crossword constructing] have been shaped by economic, social, and technological forces that have created and reproduced a culture in which women feel unwelcome, underutilized, and underestimated,” Shechtman writes.

Though her book focuses primarily on white female figures in crossword history, she is quick to point out that they are not the only ones who have felt unwelcome, underutilized, and underestimated in the puzzle sphere. People of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and members of other marginalized groups are infrequently published in mainstream outlets like the Times, which didn’t publish a Black woman constructor until 2021.

This lack of representation has social and political consequences, says Shechtman. It may communicate to solving audiences that words, phrases, and individuals associated with certain cultural groups are not suitable for the puzzle, she says, either because they are inappropriate or obscure. To wit, she recounts that a grid she submitted during her time working with Shortz, which prominently featured the answer “MALE GAZE,” was deemed too niche for publication.

Not merely a pastime, crosswords are deeply political, according to Shechtman, because of their power to act as gatekeepers of language and potential reinforcers of status quo power structures.

The longstanding idea that the puzzle references a canon of common knowledge remains problematic, she says.

“What is common knowledge? What is mainstream knowledge? Is that singular? What forms of exclusion does that actually engender?”

Shechtman’s story, and the stories of women involved in shaping the trajectory of crosswords, are placed in the broader context of what “boxes” women are allowed to fill in a patriarchal society and how they have used language and wordplay to negotiate and even break out of them.

“There’s a great haiku from [champion crossword solver] Ruth Von Phul in which she says: ‘What a paradox/Is an unbending person/Who cannot unbend,’” explains Shechtman. “That became a kind of motif for all of the women in the book, and certainly for myself. We’re all tempted by a certain kind of rigidity, a desire for control over our own image and our own relationship to our gender identity, which, in many ways, got us all kind of stuck.”