A Profound Impact

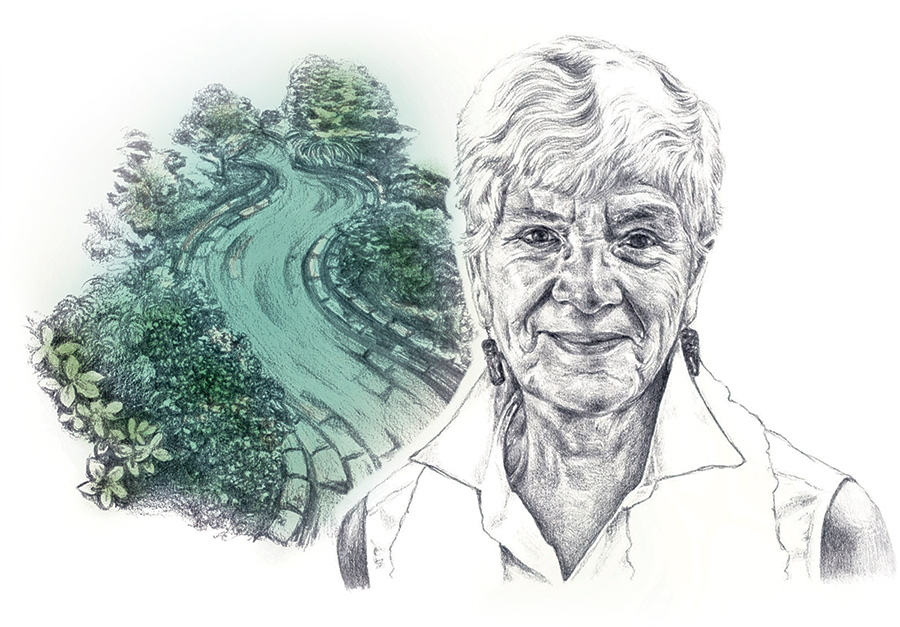

t was February 1973, and Mary Rowe ’57, a shy and quiet feminist trained as an ivory tower research economist, was about to be thrown into practice in a new job at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

As a confidential and impartial resource, Rowe was to hear concerns and ideas from members of the MIT community and do her best to help develop, and offer, both informal and formal options for resolution. By the end of 1973, she had received hundreds of visits about every kind of workplace issue from every corner of MIT: faculty, staff, students, a past president, custodians.

Some of what she heard surprised and concerned her.

“For example, virtually every working day of my first year, I received a concern that seemed like racial or sexual or religious harassment or bullying,” she says. “One of the things that hit me was how difficult it was for people to find out what the resources are, or even how to think about it. For example, when you’re a person in your 20s, you may not be sure how to take come-ons or stares or slights or bullying.”

Rowe made use of her doctoral training — she had a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University — to compile reports on what she had been told. She urged her direct superior, President Jerome Wiesner, to create a policy against harassment.

The reports led MIT to become one of the first universities in the world to have a harassment policy, seven years before the federal government released guidelines on sexual harassment.

Her reports advanced the theory that seemingly small instances formed the scaffolding of structural sexism and discrimination. Rowe would define these in other works as “micro-inequities.” She expanded on psychiatrist Chester Pierce’s concept of racist microaggressions to include “all kinds of discrimination perceived to be unfair.”

Rowe would continue using this concept of micro-inequities for decades, and coined a counterpart term, “micro-affirmations,” to describe positive feedback that can combat discriminatory views and behavior and foster a sense of belonging among people in underrepresented groups.

Now in her fifth decade at the university, Rowe has had “a profound impact on MIT,” the school has written. She handled more than 20,000 cases and helped shape policies related to discrimination, conflicts of interest, intellectual property, and research integrity issues.

In the process, she also helped to define a profession that will ensure others continue this work for years to come: the “organizational ombuds.”

Ombuds play a unique role in the workplace because of their singular quartet of standards of practice, which Rowe helped develop: independence, confidentiality, impartiality, and informality. (Informality means that visits to ombuds are voluntary and that the ombuds does not make management decisions, accept notice, or keep case records for the employer.)

Today, organizational ombuds around the world are doing what Rowe was recruited to do at MIT — advocating for systems and policies that will ensure a more equitable workplace.

“Being an organizational ombuds is a lifetime of trying to figure out how to increase the fairness and equity and belonging of the people around you,” says Rowe.

Rowe has had these hopes and goals since high school. She chose Swarthmore because she was interested in its Quaker values.

“Swarthmore was the right home for me, and it was the right platform,” she says. “The traditional values of Swarthmore were the ones that I wanted, and the deep thought about conflict and equity and fairness and inclusion — you seek a college that has those values and you grow up in it. It’s the right air to breathe.”

Now 88, Rowe continues to teach, research, write, and consult as an adjunct professor of negotiation and conflict management at MIT Sloan School of Management.

Her notes and papers have been digitized as part of the Women@MIT archive, an initiative to preserve “the work and accomplishments of outstanding women at the Institute.”

She has made much of her writing and research available online (bit.ly/MaryRowePapers) for any employee or administrator seeking guidance on workplace conflicts. Rowe hopes others will use them, particularly “Drafting a Letter,” which includes evidence-based strategies for addressing harassment, to navigate difficult situations.

“If you think about what is happening now to people who are bullied or harassed for any reason, the principal question is how to invent tools that they can use themselves or [find] people that they can go to completely safely to help find a path,” she says. “I don’t give advice, but I have learned a lot about how to help people find a path to inclusion and belonging.”