Write for the Future

RAFTING a compelling story for kids is not as easy as it looks.

Just ask Professor of Linguistics and Social Justice Donna Jo Napoli. In addition to teaching and research, she’s authored more than 80 children’s books.

“People read them and think, Boy, that’s simple! I could do that,” says Napoli. “Anybody and their aunt can write a children’s book. That’s a huge myth. It took me 13 years to sell my first story.”

“It’s an exciting time,” says Tiffany Liao ’10, a senior editor at Henry Holt Books for Young Readers. “Authors, educators, and others are pushing for more inclusive publishing — publishing that reflects our readership.” In the U.S., the under-10 age set is more than half non-white. “Our demographic is changing so much more rapidly than the adult side,” Liao adds. “The majority-minority shift happened earlier. The kids’ side is leading the charge.”

It’s a hard truth that children’s books still greatly favor white characters. According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, there are more books about bears and bunnies (27%) than Black or Brown main characters.

“As a child, I didn’t see my identity,” says Liao. “There’s a hunger for those stories, for richer, truer, stronger stories.”

Author Emma Otheguy ’09 agrees.

“The books I read at school were very formative to me, but they certainly did not represent a culturally or racially diverse perspective,” says Otheguy, who grew up in a Cuban American home. “I felt the absence very strongly as a kid.” Otheguy adored stories about hideaways, like The Secret Garden, but repeatedly encountering books with British main characters made her wonder where she fit in: “This is only something that can happen to people who live on a British moor.”

That single-perspective narrative is changing, and Swarthmore alums have their hands in the mix.

For Otheguy, who writes books with Latinx characters, it’s all about expanding what’s considered mainstream and acceptable. Her newest book, A Sled for Gabo, has been likened to Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day. In some families, when the kids troop home from sledding, they make hot chocolate. “We never made hot chocolate,” Otheguy says. “We made dulce de leche.”

Editors want authentic stories, books that “get it right” when portraying an underrepresented group. In the past, white authors might have written these tales trying to explore marginalized experiences. Today’s editors ask: Who’s telling the story? Is it their own story?

“For a while, people were asking, Why do we need diverse books?” says Liao, who is Taiwanese American. She credits groups like We Need Diverse Books, founded in 2014, for their diversity efforts. “Now we definitely know we need them. The question is, how?”

The “how” sometimes concerns Napoli.

“There’s this whole issue of lived experience,” she says. “If you push that to the extreme, it means authors can only write about themselves, which is incredibly boring and has nothing to do with a diverse society. Books need to be populated by all kinds of people.”

Can a white author write about a character of color, or vice versa? Should they? Liao takes a nuanced approach.

“There are no ‘rules,’” Liao says. “People try to cleave to rules. Instead, we truly talk to the author. What are our blind spots? Where do we need to hire an authenticity reader?” Liao says most authors welcome this extra level of care. “They’re incredibly enthusiastic. They want their books to be better.”

Accuracy is always important, but with children’s books it’s vital. Young readers are in a formative time — Liao can still remember childhood books line by line — and these books may be the first or only impression a child gets about another culture. “We really, really want to get it right,” Liao says. “We feel responsible.”

In the past, stories featuring a character who is Black, queer, or disabled might be tagged as an “issue” book. Today, kids can find Black heroes in their fantasy books or a Native detective in their mystery book. “It’s diversity within diversity,” says Liao. “Identity informs the narrative, but it’s not always the central drive.”

“These voices and perspectives belong, and there is space for them everywhere,” says Otheguy, who grew up reading mainly about white families. “It’s time to read from a greater range of perspective.”

And it’s not just new voices. Topics that used to be off-limits for younger children — sexual assault, race, gender — are increasingly part of stories for preschool and elementary children. Titles include Fighting Words, Antiracist Baby, and Gracefully Grayson.

“There’s been a cultural shift with the #MeToo movement,” says Sara Sargent ’07, a senior executive editor at Penguin Random House who works on picture books as well as books for older children dealing with issues like consent and anxiety. “In the last two years, we’ve also been increasingly moving away from gendered books. There’s a realization that kids are understanding gender at a younger and younger age, and studies and anecdotes show that many kids in Gen Z identify as gender-nonconforming.”

Though these new stories and authors are welcome, systemic barriers to change remain.

The publishing industry is 76% white, according to a 2019 diversity survey by Lee & Low Books. This affects decisions on every level, from which books get acquired to the marketing language on the book flap. New, more inclusive hires are beginning to trickle in, but they start at the junior level.

“The next focus is retention,” says Liao, who was one of only two editors of color when she started as an editorial assistant in 2013. “Are we laying the foundation that allows us to sustain this?”

Then there’s book access.

“When I go to schools, they’re reading the same Beverly Cleary books I read as a kid,” says Otheguy, who visits many campuses with outdated libraries. “Schools aren’t updating their book collections more than once every quarter-century. I think of myself as an author, but also as a book advocate. Kids need new books.”

For authors, editors, and literary agents in the children’s book world, these challenges are hard, but worth it. In a world of screens, nothing quite compares to the power of a well-written children’s novel, or snuggling with a favorite adult who’s reading aloud.

“A picture book is a concert of illustrations and words,” Napoli says. When it comes to literacy and language acquisition, the shared reading experience with a child on your lap is irreplaceable.

“We become partners with whoever is reading to us,” she says. “Child and adult share in creating the event. It’s a linguistic event, it’s an imagination event, it’s a bonding event.”

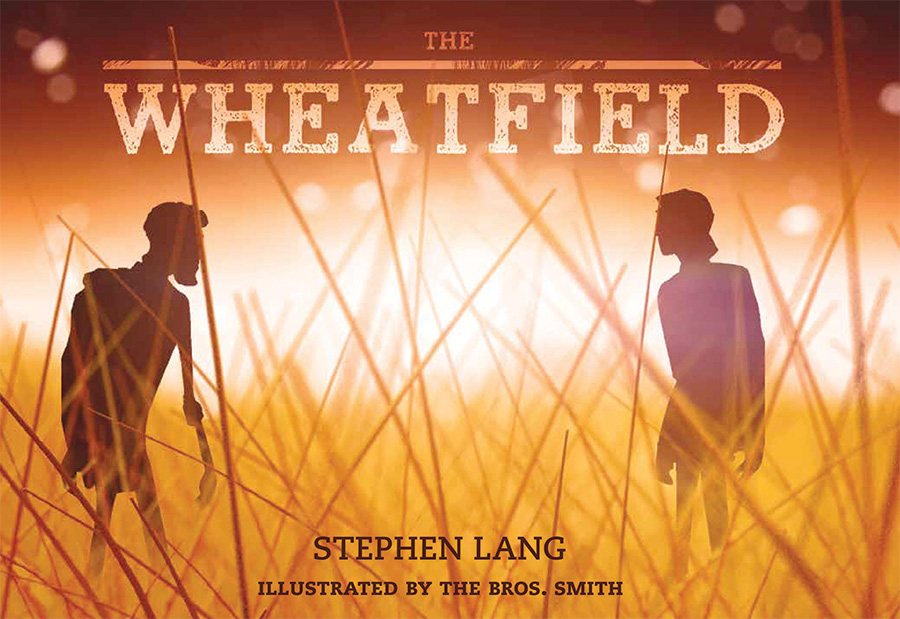

Lang says the Civil War story has increasing relevance today. “It goes beyond North and South, it goes beyond blue and gray, or red and blue. It goes to the core of being human,” he says. “Despite our differences, we share a basic, common humanity.”

While The Wheatfield spotlights kindness and compassion, Lang says authors shouldn’t force a message when it comes to children’s books. “The obligation is to tell a good story,” says Lang, who has performed stories like Purman’s on Broadway. “If you’re just trying to impart a lesson, forget it.”

Children’s books can be revolutionary. At a time when many people wonder how to bridge divisions and promote tolerance and diversity, Lang points to the arts.

“Art can subvert that whole process” of injustice, says Lang. “It’s a way to disarm hatred. It’s a way to penetrate cynicism. It’s a way in.”