Power

of

Place

photography by Laurence Kesterson

Power

of

Place

photography by Laurence Kesterson

It was the first time Jean had been to this North Philadelphia neighborhood. She saw loads of trash and abandoned houses, but also strings of bright Christmas lights on people’s homes.

After that visit, she never quite left.

For more than 16 years, Jean has been a presence in Fairhill, an area once notoriously known as “The Badlands.” At the corner of Ninth and Indiana streets during the crack epidemic in the 1980s, dealers openly sold drugs, and addicts shot up and slept in an adjacent derelict Quaker cemetery. By the time Jean visited, community and Quaker activists had spent 10 years clearing out the dealers and cleaning up the cemetery.

— Jean Murdock Warrington ’71

“I was touched by their story,” Jean says, “so Peter and I started working with the project.”

Ramos Bautista, of Puerto Rican heritage, has lived in Fairhill for 33 years. Streeter was the African American pastor of the Quaker meetinghouse-turned-Baptist church near the burial ground.

The 5-acre fenced graveyard is an oasis of green in the middle of concrete, rowhouses, and newly built low-income and senior housing. It takes up a city block, sprinkled with shade trees and rows of tiny, weathered headstones protruding like gray half-moons out of the ground. Plain grave markers are common to Quakers, who espouse equality among people.

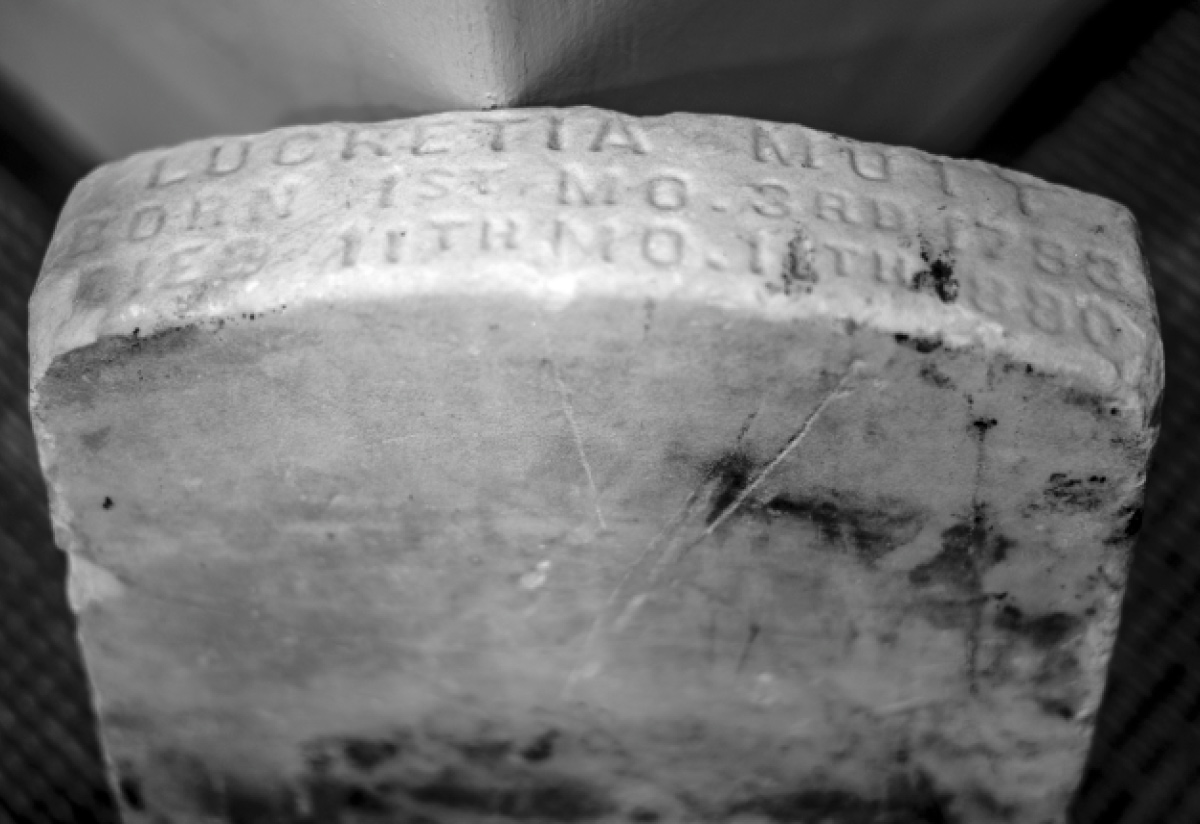

Buried in this national historic site are Swarthmore co-founder Lucretia Mott, a white Quaker who in the 19th century advocated equal rights for women and enslaved Africans; Robert Purvis, a Black abolitionist with ties to the Underground Railroad; and Edward Parrish, the College’s first president. Jean and Peter, Quakers who live in Northwest Philadelphia, are carrying on Mott’s legacy and the original purpose of the 300-year-old space: burial ground, playground for children, and gardens.

“We’re not as brave as Lucretia Mott,” says Jean. “We aren’t going after major public policy change or overthrowing major institutions. We’re doing more service. We’re inspired by her and ask, ‘WWLD: What Would Lucretia Do?’

“She believed in education. She thought it was the way to freedom. We’re trying to help kids learn how to read well. And we’re trying to make gardens where people come outside to a safe place and they get to know each other.”

A constant in the neighborhood

In the 17th century, it was part of a larger site that William Penn gave to his English friend George Fox, founder of the Religious Society of Friends, of which Penn was a member. When Fox died in 1691, he willed the property to Philadelphia Quakers for stables, a meetinghouse, a school, a burial ground, a playground, and gardens.

A meetinghouse was built around 1703, and the burial grounds opened about 1707. The cemetery was not used often until the mid-1800s, when it was enlarged; Mott and her husband, James, helped raise money for it. Mott biographer Margaret Hope Bacon H’81 applied for historic designation for the burial ground, which was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999.

The cemetery is no different from others owned by the Quakers, with its small cookie-cutter headstones and indistinguishable graves. But it is notable because of who lie beneath the soil: some of the stalwarts of the 19th-century abolitionist movement in Philadelphia.

Mott is perhaps the best-known. She spoke against slavery and supported equality for women, African Americans, and Native Americans. She and her husband were among the co-founders of Swarthmore College, as was Parrish. Purvis opened up his home to enslaved Africans and shuttled them through the Underground Railroad. Bacon has written that he likely bought his family plot through his friendship with the Motts. All Quakers were not so tolerant; some were slave owners before 1776, when the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting prohibited members from enslaving people.

Purvis’s wife, Harriet, was a co-founder with Mott of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. They were among the women who had met for an anti-slavery convention in the newly built Pennsylvania Hall in 1830 before a pro-slavery mob set it on fire. Mott was also an organizer of the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, N.Y., which started the women’s movement.

A forgotten cemetery gets new neighbors

But by the 1980s, Fairhill had fallen into despair, marked by consistently high poverty, distressingly low student test scores, and entrenched crime. Contributing to the neighborhood’s plight was the cemetery.

“No one came around to maintain it,” recalls Ramos Bautista, the community activist. For years, she and neighbors thought it was a pet cemetery because of the small headstones. Bacon noted in a 1999 article in Friends Journal: “It was a tangle of weeds, discarded tires, trash, and garbage, surrounded by a gap-toothed fence and gutted sidewalks, a menace to an already decaying neighborhood.” Bacon, who helped restore the cemetery, died in 2011.

“We had people shooting up on the corner,” says Ramos Bautista. “We had people laying around. You don’t see that around the cemetery no more.”

The change began when neighbors started challenging the dealers and reached out to the Quakers to clean up their cemetery.

“I would stand on the corner and disperse them and call 911 because a lot of the kids got killed around here,” says Ramos Bautista. “We used to have vigils out there every night so the drug dealers wouldn’t sell. We would give coffee to the cops to come sit out there with us. The neighbors pulled together to take the community back. It was hard, but we did it.”

Mural Arts Philadelphia painted eight murals in the neighborhood with such figures as Mott, Purvis, Harriet Tubman, and Martin Luther King Jr. Ramos Bautista made such a difference that a mural was painted in her honor overlooking Ninth and Indiana. “Peaches Ramos was our leader like Lucretia Mott was earlier,” says Jean. “She was a peaceful warrior. She was fearless.”

A HISTORIC INFLUENCE

It took her 15 years of agitating her fellow Quakers about the condition of the cemetery and the neighborhood before anything happened, she said. In 1985, the meetinghouse and cemetery property were sold to Ephesians Baptist Church. Friends from Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting, which represents the eight monthly meetings in the city, purchased the cemetery in 1993, and Fair Hill Burial Ground Corp. was formed to maintain it. In 2009, it was renamed Historic Fair Hill. The meetinghouse remained separate and is now owned by St. John Memorial Baptist Church.

For several years, Quakers from Philadelphia and other areas worked to clean up the burial ground and raised money to replace missing sections of a wrought-iron fence. By the time Jean arrived in 2004, the revival of the cemetery and the surrounding community were intertwined. She was named program director of HFH that year and executive director in 2016.

Fair Hill staff members and volunteers carved out gardens where children now grow flowers, fruits, and vegetables. They joined with residents to plant 135 trees and build seven satellite gardens in the community, and they created green spaces for play. HFH now hosts tours and festivals in the cemetery, and partners with schools in the area.

Even with the pandemic, Jean and Peter continue to work in the gardens and donate the bounty to local residents. They set up free-book tables at the neighborhood’s Julia de Burgos Elementary School — named after a Puerto Rican poet and civil rights activist.

HFH provides books and reading tutors at the school. Among the supporters are parents and teachers at the suburban Plymouth Meeting Friends School. As part of a project called “Building Bridges,” books and supplies were donated and letters were written advocating fair state funding for education. Since the school upholds the Quaker values of social justice and activism, the group felt that “we should be trying to engage parents and families acting on those values,” says Rebecca Smith Heider ’96, a project member.

These days, Peter uses Zoom to tutor second and third graders at de Burgos School in reading. A few years ago when he noticed the library was closed, he had asked the vice principal if he would be interested in reopening it. “He looked at me like I’d asked a very stupid question,” Peter recalls. “He said, ‘Of course.’”

So staff members and volunteers dusted off the bookshelves, cleaned up the room, and bought and cataloged new books. In 2016, the library reopened with 12,000 books. It welcomed classes four days a week before school was closed because of the pandemic.

— Jean Murdock Warrington ’71

Resting in plain site

It wasn’t a pet cemetery, of course. Early Quakers were strictly committed to simplicity and equality, and they abhorred the intricate, aggrandizing monuments common at the time. Most Quaker communities did not use any grave markers at all until the mid-19th century. When they did begin to use them, Quaker burial grounds placed restrictions on the stones within their boundaries: the size, shape, and even what could be engraved thereon. While Victorian cemeteries burst with soaring obelisks, realistic statuary, and lengthy inscriptions, Quaker burial grounds sprouted short, rectangular stones, briefly identified with names and dates.

Though neighbors thought Fair Hill was a pet cemetery because of the simple headstones, on the contrary, some of Philadelphia’s — and Swarthmore College’s — most notable 19th-century activists are buried there. The most famous grave at Fair Hill belongs to Lucretia Mott. Renowned in her own time, Mott was an influential reformer promoting abolition, women’s rights, and peace; she is also counted as a founder of Swarthmore College. Swarthmore’s first president, Edward Parrish, who was also a pharmacist by trade, a Quaker by faith, and an abolitionist by conviction, is interred there as well. So are Robert and Harriet Forten Purvis — prominent members of Philadelphia’s free Black community who, like their friends the Motts, were active in anti-slavery work and supported women’s suffrage.

To learn more about Fair Hill Burial Ground, come visit us at the Friends Historical Library, as we hold Fair Hill’s archives (archives.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/resources/4069fahi). There were a few burials on the land as early as 1707, but it wasn’t until 1843 that a Joint Committee on Interments was formed and burials began on a more regular basis.

The College has burial registers, lot records, publications, and other related items documenting more than a century of active use. Don’t get confused when you learn that the first burial after interments resumed in 1843 was one “John Hare.” He was a man, not a rabbit — take it from me, you Friendly archivist.

— Celia Caust-Ellenbogen ’09, Friends Historical Library Archivist

Their efforts here have been varied. Once, the school’s police officer and baseball coach told Peter that he couldn’t get physicals for some seventh graders who needed them to play baseball. Peter, a doctor, conducted not only their physicals but also those for members of a running club and basketball team, and for softball teams at a nearby junior high school. At de Burgos, Jean raised money to pay bilingual parents $15 an hour to work as aides for kindergarten to second-grade classes. These women, trained by teachers, help translate and provide a comforting presence.

“The more money we can raise, the more hours, the more people we can bring in to support our neighborhood schools,” Jean says.

Adds Ramos Bautista: “They take the time to come over here and help the kids from the neighborhood. They don’t have to do that.”

MAKING THE WORLD A BETTER PLACE

Recently, Peter was corresponding with his Swarthmore roommate, Felix Rogers ’69, also a physician. “He was ruminating about why he’s still working,” Peter says. “He’s working for the same reason he started and for the same reason I did. He was saying, ‘I’m still working because I want to make the world a better place in any way I can.’”

Says Jean: “At Swarthmore, I learned that our job is to help make the world better. George Fox saw an ocean of darkness and death, but over that an infinite ocean of light and love. At Historic Fair Hill, friends and neighbors across cultures are trying to create a more just and peaceful world.”

Although the area around the cemetery has improved, the “Badlands” epithet still clings to Fairhill.

“I hate that name,” Ramos Bautista says. “We’re human beings. There are decent people out here.”

The disabling issues facing poor communities like Fairhill are deep-rooted: racial and health disparities, inadequate schools, poverty, unemployment. It is a community of contrasts: rich with churches, three of them across Germantown Avenue from the cemetery; tidy and untidy blocks, new and old housing stock, abandoned factories, empty lots littered with trash, gutters with hypodermic needles, a commercial strip.

Jean and Peter are frustrated at the forces that allow communities like Fairhill to be neglected.

“These are systemic problems that don’t get better quickly,” says Peter, who also helps with voter registration with the Fair Hill Neighbors. “These are Philadelphia problems, these are United States problems, and solving them is going to be a long process.”