A New Age

A New Age

Swarthmore 80 years ago was both very different and much the same as it is today. For these centenarians, historical events are just one part of their extraordinary lives.

Among the experiences these Swarthmoreans have lived through are the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II. Despite enormous challenges, they also found joy in art, literature, and family.

As for living to 100 and beyond? It’s complicated. But special, too.

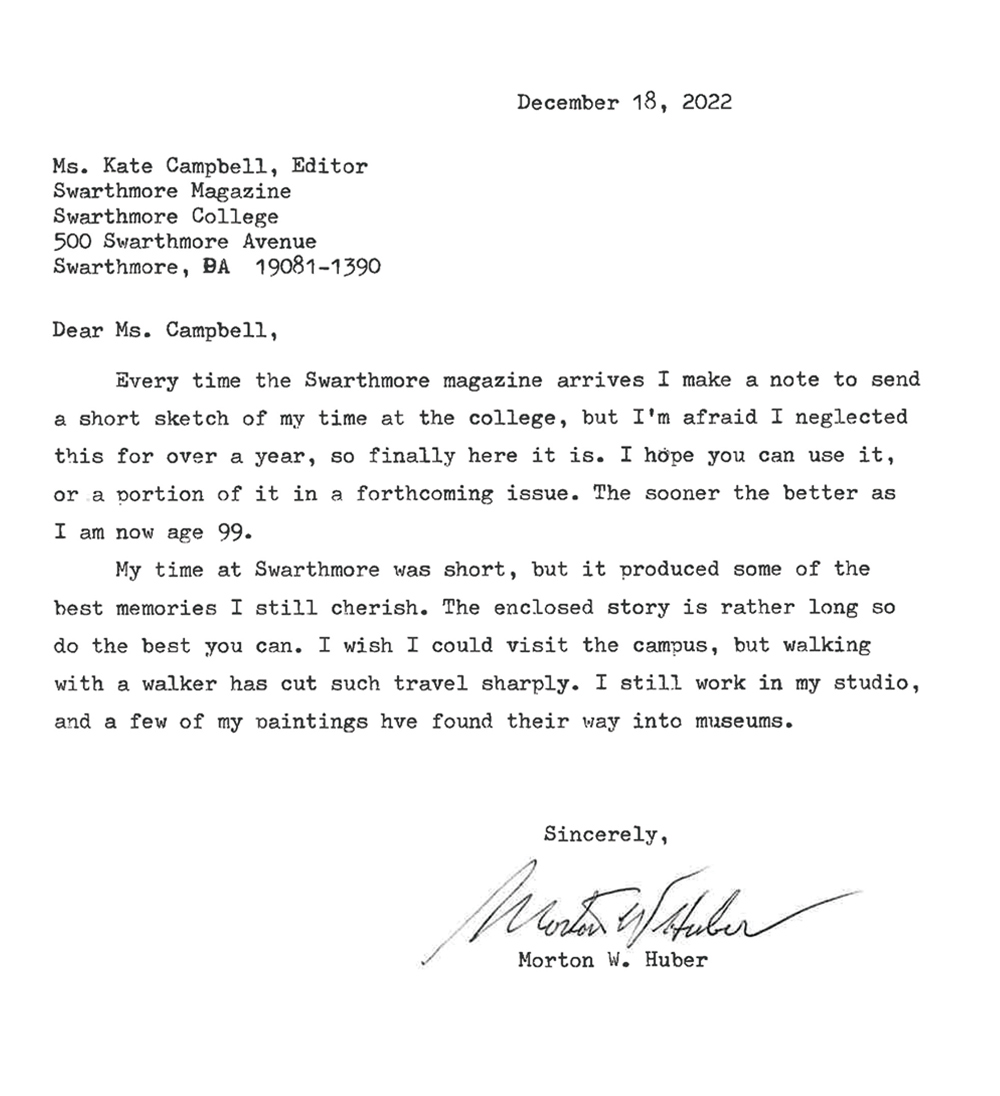

Morton Huber

do something you love

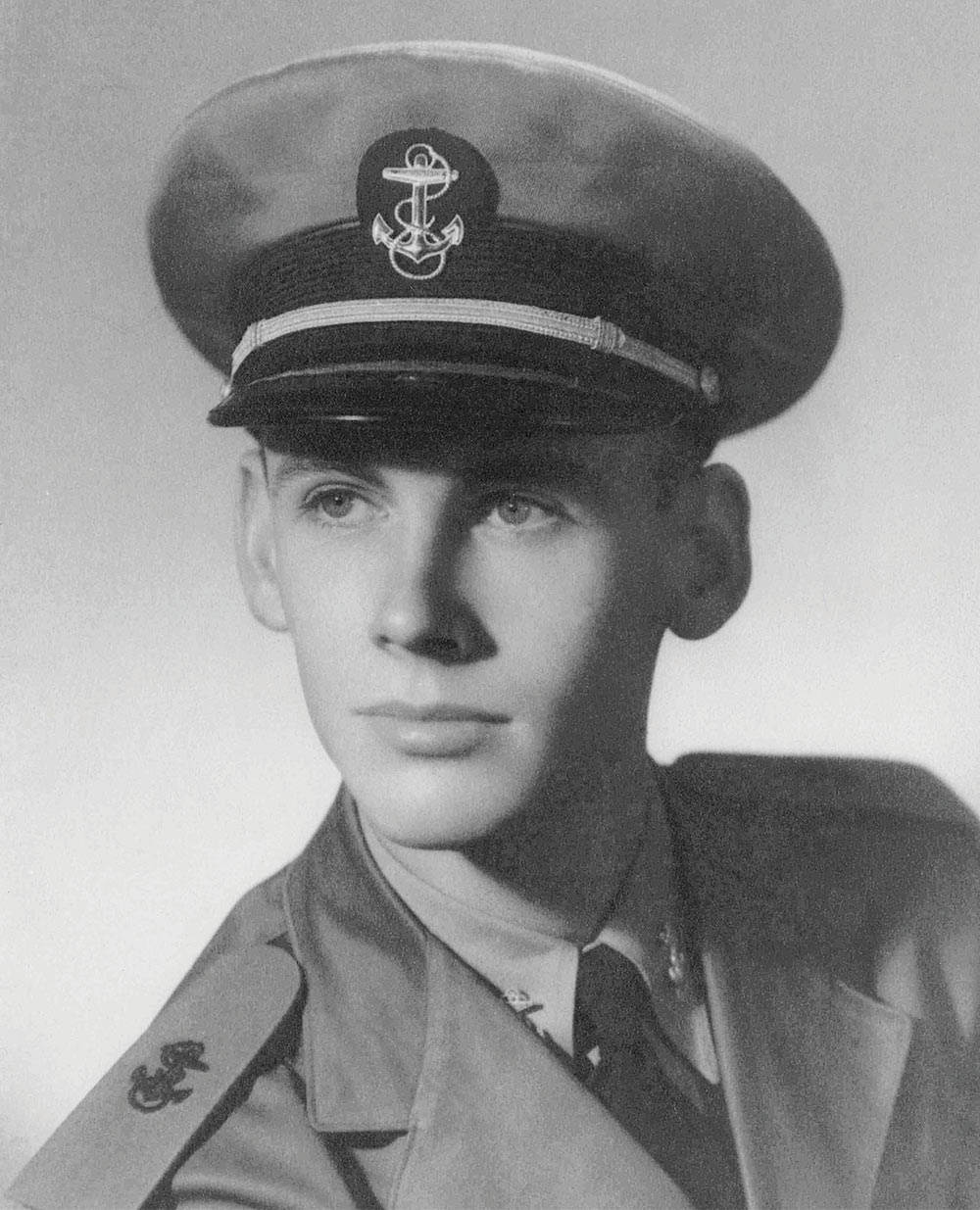

Huber had started college at Johns Hopkins University, but that quickly came to an end when the U.S. entered the war. He enlisted in the Navy. At Swarthmore, he took special courses in gunnery, navigation, and communication, as well as regular classes like chemistry and math. The sailors marched and drilled about campus, performed daily calisthenics, and lived together in one dorm.

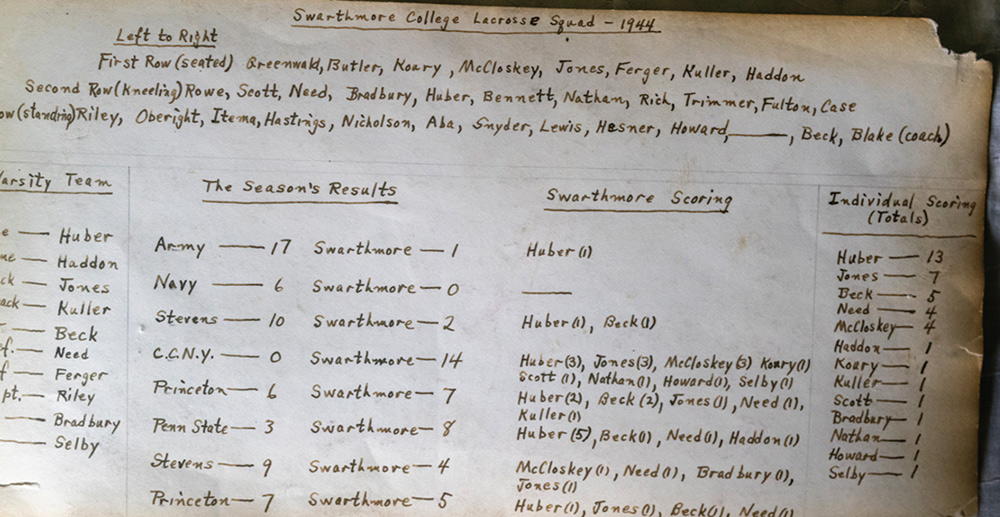

He also had time to play lacrosse. Johns Hopkins was a leader in lacrosse, and “by the time I got to Swarthmore, I was pretty good with a stick,” he admits.

Indeed, he was Swarthmore’s high scorer. Swarthmore’s mixed civilian-sailor team beat Princeton and Penn State.

“We fielded a pretty good team,” says Huber fondly. “Our first game was West Point. Most of them had never seen a lacrosse stick.”

Science had long been a passion for Huber, and after the war, he became a biochemist. “I built a laboratory in my parents’ basement,” he says. “I stocked it with a fine microscope from an antique store.” He returned to Johns Hopkins to finish his degree and earned a Ph.D. from Cornell University Medical College.

While teaching chemistry at Emory and Henry College, Huber met Kyoko Ushio, a student sponsored by the U.S. armed forces in Japan. They married in 1962 at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. They lived in Japan for nine years. Huber was a professor of biochemistry and environmental science at the Kanazawa Institute of Technology in Kanazawa, Japan. He also pursued his growing interest in art.

“In my free time, I went out and worked with my cameras and my paintbrush,” he says.

He studied vanishing cultures of nearby mountain villages, including kamishibai, “paper theater” made of cardboard performed by itinerant storytellers who traveled by bicycle.

kesterson

“I had a dual career,” he says. “I was sort of doing STEAM before it came along.”

After a 20-year career in biochemistry, Huber published five books about art and Japanese culture.

He taught painting for many years on visits to England and became a fellow of the British Royal Society of Arts. Stateside, he served as president of the Baltimore Watercolor Society. His wife Kyoko, a pianist, still teaches at High Point University in North Carolina. Huber’s watercolors and photography have been shown in galleries around Baltimore.

This July, Huber turned 100. He’s been happily married for 61 years and still paints in his home studio in North Carolina.

“Pick something as a career that’s really enjoyable, something you love to do,” he says. “Whatever you do, do something helpful to society. We need good people.”

A Sense of Purpose

Attaining the milestone of a century of life was, she noticed, becoming increasingly common.

What was their secret?

Thomas challenges the premise of the question. Having spent years providing care in hospices, patients’ homes, and assisted-living environments, as well as serving as a medical director in aged-care facilities and teaching geriatric medicine, she focuses less on chronological age and more on function and quality of life.

“Everybody ages differently,” she says.“You can have a centenarian who is functional, doing everyday activities. And then you can have a 100-year-old who is bed-bound and nonverbal.”

Do those fortunate enough to still be living full lives at 100 or beyond tend to share any traits?

“It’s a mixture of good genetics, environment, and a healthy lifestyle,” she says.“Having a purpose in life, a reason to get out of bed. A social life helps, too. And then you’ve got to have some luck.”

For Thomas, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to geriatric medicine, and it was the field’s personalized, holistic dimension that fascinated her the most.

“Treating an elderly patient is all about finding out what’s most important to that person,” she says. Whether it’s making it to a grandchild’s wedding, or prioritizing quality of life over quantity, Thomas says, “you have to listen, and figure out how to help that person to do the things they want to be doing.”

Growing up in a multigenerational home in the Bronx, Thomas helped to care for all four of her grandparents.“When I was 10, my grandmother died in our home, in home hospice care,” she says. “My grandfather had Parkinson’s and died of a heart attack. My other grandmother had dementia.” These experiences were her first exposure to the profound and varied nature of end-of-life care.

After studying biology at Swarthmore, Thomas earned her M.D. at Temple University, then worked at several hospitals, elder-care facilities, and medical schools across the United States. Her focus was then on treating the most neglected members of society.

In the early 1990s, she was on the front lines of Philadelphia’s HIV epidemic. She was director of and taught at Graduate Hospital Ambulatory Clinic, an affiliate of the University of Pennsylvania. After that, she moved into geriatrics.

“I was taking care of the oldest of the old, the sickest of the old,” she says.

Thomas came to believe that, for older patients, less can often be more. Too frequently, she saw aggressive treatment making it impossible for people to have a happy old age.

“Sometimes, side effects of medication can interfere with what a patient wants,” she says. “As a physician, you have to respect where your patients are at.”

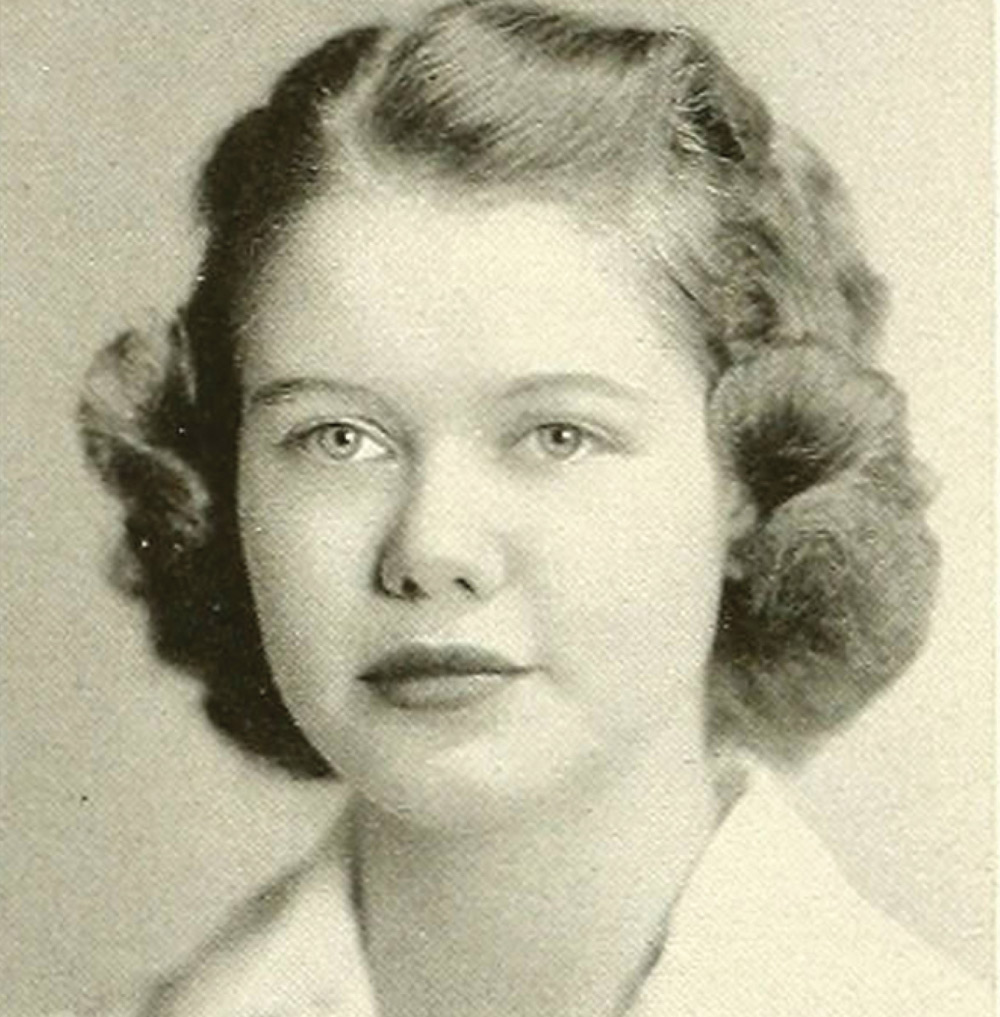

Lucy Selligman Schneider ’42

The Writing Life

“Thee is charged 30 cents for being late for breakfast,” reads a slip of paper signed by Swarthmore’s dining hall dietitian in 1938.

Schneider also was once fined 50 cents for eating two dinners. She’d been invited to a campus dance, and thought she should eat early before meeting her date. To her surprise, the dance involved dinner, and she was caught double-dipping.

Much has changed since Schneider’s college days. At 102, she is one of the last surviving members of her class.

Her path to Swarthmore was due to unusual world and family events. The youngest child in a politically active Jewish family, Schneider grew up in Louisville, Ky. Her father was a lawyer and past chair of Kentucky’s Republican Party. Her mother marched in suffragist parades, pinning a “Votes for Women. Hurrah!” ribbon to Lucy’s baby carriage, and voted for the first time in the historic 1920 election.

She remembers talking into the night with her brother, Joe, about T.S. Eliot, mental arithmetic, and German poetry. Joe attended Swarthmore, and was expected to graduate in the Class of 1937. But when Franco’s Nationalists began an uprising in Spain, Joe secretly left college and traveled to Spain to help stop the fascists.

“His laundry didn’t come back from college,” says Schneider, explaining that he used the “Railway Express” to send his laundry home from Swarthmore to Kentucky, using a special case that traveled by train. When the case didn’t arrive, his family began making frantic phone calls trying to locate their son.

Joe eventually wrote home explaining his belief that it was more important to fight fascism than get a college degree. “If I don’t come back, use my money to send Lucy to Swarthmore,” he wrote. He died two months after reaching Spain, the first American casualty of the Spanish Civil War.

Lucy was 16 when her brother died. Her sister Augusta had already graduated from Vassar. She enrolled as a freshman at Swarthmore in the fall of 1937.

Still distraught when she arrived on campus, Lucy was invited to lunch by President Frank Aydelotte and his wife. Joe’s professors sought to comfort her, too, but all the attention was difficult. Grief overwhelmed her. As for studying, it was hopeless. She couldn’t concentrate, flunked two of her classes, and turned in a blank exam book for one course. The dean of women suggested she leave Swarthmore and try Middlebury instead: she excelled in French and Middlebury was known for its language programs.

“I decided I was just gonna have to work harder,” says Schneider. She took summer classes at the University of Louisville to make up for her credits, and eventually found her academic footing at Swarthmore.

On May 25, 1942, she graduated Phi Beta Kappa. Congratulations arrived by telegram. She was married briefly and has one daughter, Lucy Schneider McDiarmid ’68.

In 1955, Schneider went into publishing. Legendary editor Margaret McElderry hired her at Harcourt, Brace, even though she failed her typing test. Thus began a 16-year career as a children’s book editor.

However, in 1972, before the Newbery Awards were announced, Harcourt publisher William Jovanovich fired Schneider, along with McElderry and two other colleagues.

“He said Margaret was no longer the wave of the future,” says Schneider. “That she was old-fashioned. [We] were fired because we were connected with her.” Schneider became a freelance editor, continuing to work for 30 years. (McElderry went on to edit Newbery winners under her own imprint.)

As for the key to a long life, “I just stuck around,” says Schneider, who exchanged birthday cards last year with her lifelong Swarthmore friend Mary Weintraub Delbanco ’42. Her 100th birthday was subdued, since it took place amid the pandemic in 2020, but the family held a party in 2021.

She still keeps active and, like her brother once did, continues to stand up for her beliefs. When the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade in 2022, Schneider protested in New York’s Washington Square Park. She arrived by wheelchair, accompanied by her granddaughter, Emily Savin. Her sign read “Centenarian for Choice.”

Being a centenarian brings a certain amount of attention, but also sorrow.

“It’s not a great hunk of happiness to live this long,” says Schneider. “The trouble is everybody you ever knew has died. All the people you went to school with. If you’ve forgotten somebody’s name or forgotten some incident … there’s nobody left to ask.”

Betty Glenn Webber ’43

her social life continues to bloom

But then, she drops a little hint.

She is, she says, a joyful person. “I’m not the least bit given to depression,” says Webber. “I’m comfortable with my existence. Plus, it just so happens that the course of my life has not involved heavy drinking.”

Webber’s cheerful attitude was cultured by her relationships, and her delight in conviviality really took root at Swarthmore. “It affects the whole of your life, having a liberal arts education,” she says. “But most importantly, I have had close friends among the alumni.”

Her social life continues to bloom.

She plays bridge, and four times a week drives to a pool for group exercise. “Those people are like my second family,” she says. “And they would no more park in Betty’s parking space than they would fly.”

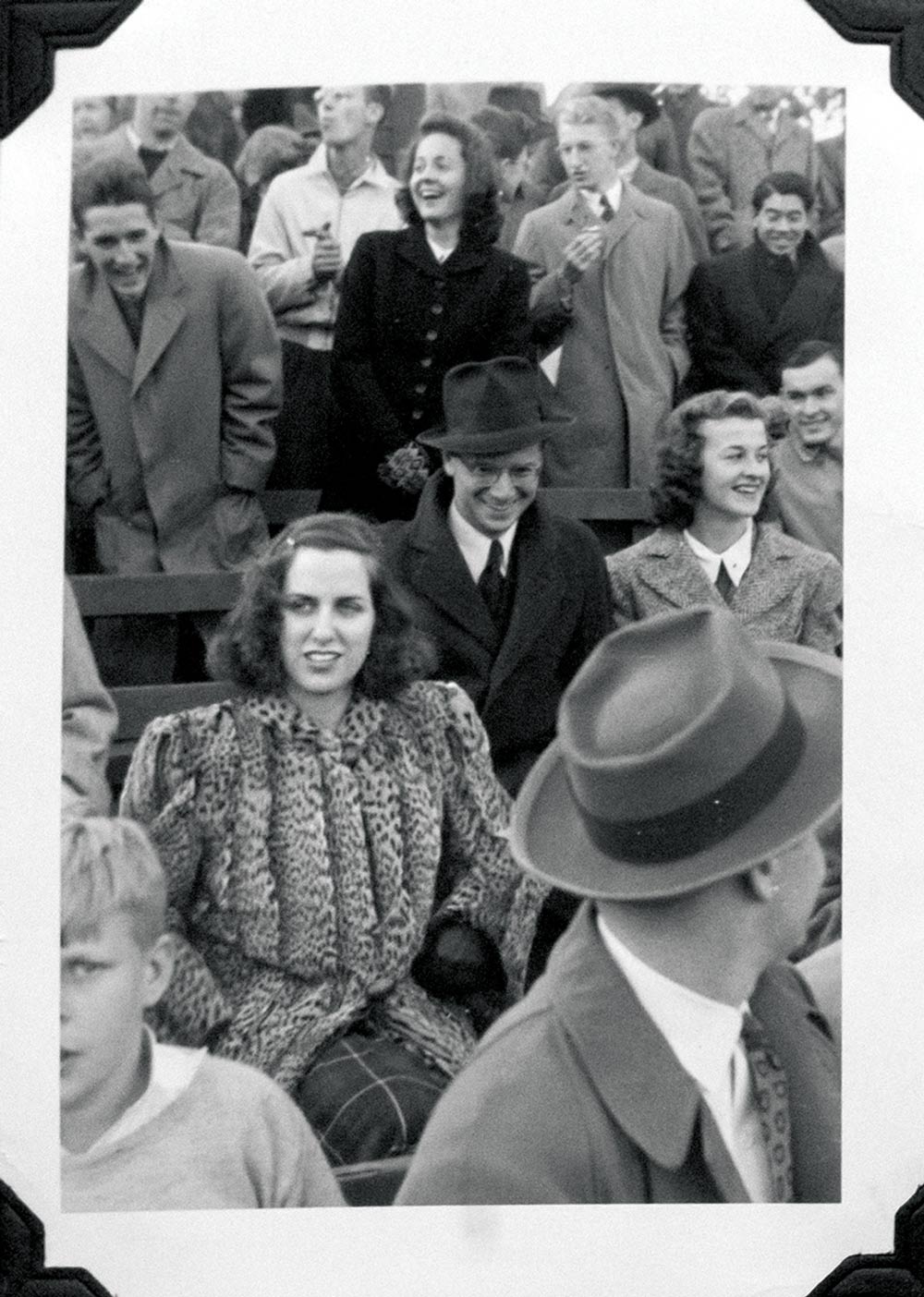

On Webber’s first weekend at Swarthmore, Britain declared war on Germany. By her junior year, she was noticing a drop-off in the number of male students.

Life had serious challenges in those days, but, Webber looks back on her time at college with fondness. Her memories stand against the backdrop of a society that had shared clarity and focus.

“The whole country was probably as united as it’s ever been,” she says. “People were public-spirited. From that standpoint, it was a rewarding time to live. We could use a little of that unity right now.”

After graduation, Webber and her late husband moved to his home state of Michigan, where they had three children, who gave them three grandchildren. Ever committed to furthering the common good, Webber spent much of her time volunteering in the community.

“At 101,” she says, “what bothers me is my inability to contribute to a reasonable degree.”

She is on the board of a local food pantry, and was always active in her church, where she still takes part in a women’s study group. “I do it because I can and because I should. If I quit, there would be nobody to do it.”

At the same time, Webber doesn’t hesitate to make a change when she detects a violation of her values.

Just a few years ago, in her 90s, she left her church of two decades due to its anti-gay stance.

That meant saying goodbye to old friends and switching to a different congregation where she didn’t know a soul.

“I chose to switch to a church whose most important mission is that their door is open to everybody,” she says. “Absolutely everybody is welcome.”

Volunteering a little less these days, Webber, ever the English major, loves devouring British fiction.

“I’m 101 years old, so what do I do? I mostly read.” She participates in a book discussion group, and it’s that practice of open-minded conversation she values most of all.

“I’d like to be remembered as someone who was willing to see the good in most people,” she says. “Someone who could be civil and open with people I didn’t necessarily agree with.”

— TOMAS WEBER

John Wenzel ’47

I Don’t Want the War to be Forgotten

“Pearl Harbor changed all of that,” says Wenzel. “It interrupted a Sunday morning bridge game in my fraternity house.”

Soon after the Dec. 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor, Wenzel enlisted in the Aviation Cadet Program in the Army Air Corps. He was 19.

“I had never been near a plane and never owned a gun,” he says. He boarded a train from New York filled with new recruits and completed basic training in Miami Beach. Next came a series of flight schools.

“It was very competitive and I was starting from scratch,” he says. The training took 20 months.

After he earned his cadet wings, Wenzel completed six more months of flight training before heading to Pisa, Italy, to fly the P-47 Thunderbolt.

“It was exactly what I had hoped for. I didn’t want multi-engine planes; I wanted a fighter plane. I didn’t want to go to the Pacific; I wanted to fight the Nazis in Europe because they were the greater immediate threat to civilization.”

Wenzel didn’t talk about his war experiences when he returned home. He refers to the war and its aftermath as “the dark time.”

One thing he knew: He couldn’t go back to being a carefree college kid anymore. He switched schools, choosing Swarthmore because of its strong academic reputation. This time around, he focused on his studies and lived at home with his parents in Philadelphia.

“We were the family handing out sandwiches, not asking for sandwiches,” he says. “However, I was at the right age to see it all, and to wonder why the long lines of unemployed couldn’t work in the empty factories.”

At Swarthmore, he majored in economics, but “had more credits in English literature.” He liked to paint. He loved jazz and golf. He kept the war buried and worked in finance, first at Chase Bank in Puerto Rico in the foreign credit department, then in New York for David Rockefeller. He joined the Ideal Corp., an automotive-parts manufacturing company in Brooklyn, and worked his way up to become its president. When Ideal was acquired by Parker Hannifin, he headed the automotive division.

Wenzel married in 1953. He and his wife Alice were married for 52 years until her death in 2005. They have two daughters, Emily and Abby, two granddaughters, and one great-granddaughter.

As his 100th birthday approached, Wenzel decided he finally wanted to make a statement about the war. He agreed to an interview with a New York Times reporter and, in an April 2023 feature (nyti.ms/48nD598), shared the story he’d never told.

Many readers reached out to him. He’s glad of that. “I don’t want the war to be forgotten,” he says.

He hopes younger people will recognize the tremendous sacrifices people made worldwide to defeat such a grave threat to civilization. On his 100th birthday, Wenzel’s family and friends toasted him with champagne. He no longer plays golf or travels, but he still loves jazz and art.

Life at 100? “It’s very difficult,” he says, “and special at the same time.”

share your story

Please write to us:

Swarthmore College Bulletin

500 College Avenue

Swarthmore, PA 19081-1306

or email bulletin@swarthmore.edu and tell us about living in your 80s, 90s, or 100s.