Star Struck

n July 12, the James Webb Space Telescope science team unveiled its first images to the public. For the NASA telescope, they were the equivalent of Neil Armstrong’s first words on the moon. Behind the scenes, scientists had worked six weeks to select and enhance the best images for maximum emotional impact.

Joshua Sokol ’11, a freelance science journalist, was one of the few non-JWST members who had a chance to witness this process. In a New York Times article this summer, he captured the wonder and jubilation of the science team as they laid eyes on galaxies, stars, and gas clouds that had never been seen before. Sokol also explained the hard science that goes into producing an aesthetically pleasing image. (Pro tip: Even when the light is in infrared wavelengths the human eye cannot see, you should color the longer wavelengths red and the shorter ones blue. This rule of “chromatic ordering” produces images that make sense to the human brain.)

After graduating, Sokol landed a job at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md., which is the science operations center both for the Hubble and Webb telescopes. (It will also be mission control for another one, the Nancy Grace Roman ’46 H ’76 Space Telescope, currently scheduled to launch in 2027.)

While working as a data analyst at STScI, Sokol learned about the image-processing tricks of the trade, knowledge he drew upon for his New York Times article. For example, in “Pillars of Creation,” the earth-toned colors were placed at the bottom. In space, there is no up or down and therefore no particular reason to do this. But art historian Elizabeth Kessler, whom Sokol interviewed for his article, explains that the human brain reacts to the picture as it would react to a landscape. That is why the image, released in 2007, became so popular, and was Sokol’s favorite even as a young child. Surprisingly, he says, “The image processing people [at STScI] actually didn’t like that picture that much. It’s an exaggerated style that they pulled back from later on.”

Jaw-dropper

Swarthmore’s strong connection to JWST has been 25 years in the making: Nobel laureate John Mather ’68, H’94 is NASA’s senior project scientist on the mission.

Jensen described the pictures as “jaw-dropping” and explained his excitement over JWST’s ability to show astronomers more about planets that formed around other stars.

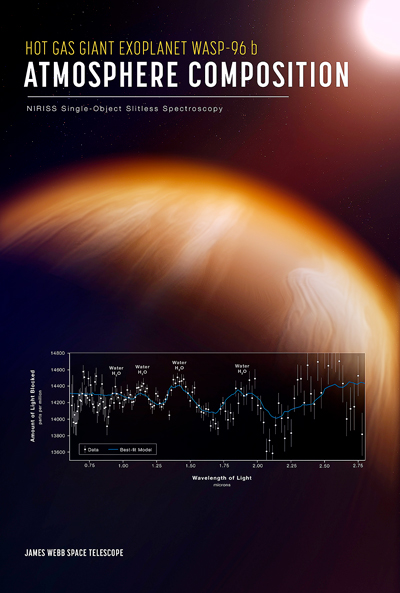

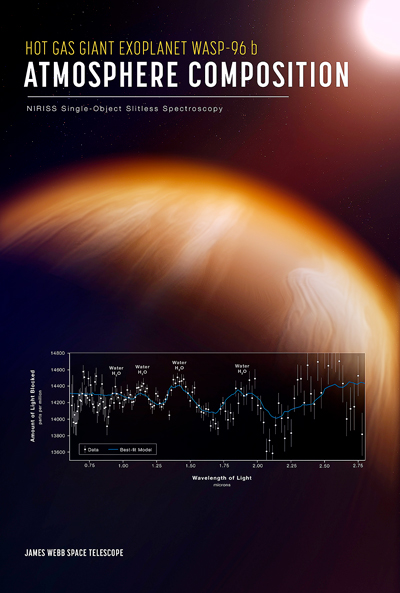

“For the vast majority of [planets around other stars], we know how much mass they have and what their radius is, but not a whole lot more than that,” he says. “JWST will be able to look at the atmosphere of those planets and help us start to determine their gas composition.” He also recounted how JWST images of a distant exoplanet labeled WASP-96b left him stunned.

“I gasped out loud when they put up a picture of the spectrum of WASP-96b’s atmosphere, and it honestly brought a tear to my eye,” he says. “It’s exciting to me that we can do this. I started my career when we didn’t even know about planets outside our solar system, and now we can determine that water is a prominent feature of a [distant exoplanet]. I’m amazed at how far we’ve come.”

Toward the end of the program, Jensen explained that he is most excited by the prospect of learning more in ways that he cannot yet anticipate.

“One of the great things about being an astronomer is to look at something, such as a new image or work that someone else has done, and see something that you never even expected. Some of the most amazing discoveries so far have come out of left field.”

The job at STScI could have been an “on-ramp” for a career in astronomy, but Sokol had other ambitions. At Swarthmore, he had a second major in English literature, and took a literature course every semester. “I knew as an undergrad that science writing was a profession, and on paper that would be the ideal fusion of my interests,” he says.

To turn his dream into a reality, Sokol studied for a year in MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing. Since he finished in 2015, he has compiled an eviable portfolio. He traveled to Japan to write about methylmercury poisoning and to Senegal to write about mosquitos. He has won prizes from the American Geophysical Union and the American Institute of Physics. One thing he didn’t write about was the Hubble Space Telescope. It felt too close to him, and too much like a conflict of interest.

But when the JWST launched on Christmas 2021, he decided, “I really don’t want to sit this one out.”

In every respect, the unveiling of the pictures was a public relations triumph for NASA. John Mather ’68 H’94, the lead project scientist (see “Combining Forces,” Spring 2021) stood onstage with NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and accepted the well-earned applause of journalists and NASA employees alike. But Mather gives all of the credit to Pontoppidan’s team for producing such spectacular images: “They did brilliantly, didn’t they?”

For Sokol, despite the thrill of seeing Webb’s baby pictures, the space telescope he grew up with is still the one closest to his heart.

“Hubble images piqued my interest in the communication of science, because of the way that they were both scientific and could harness feelings,” he says. “If you argue about what is the greatest science experiment in human history, Hubble should at least be considered.”