“Woman has long been excluded from the privilege of speaking to the people.”

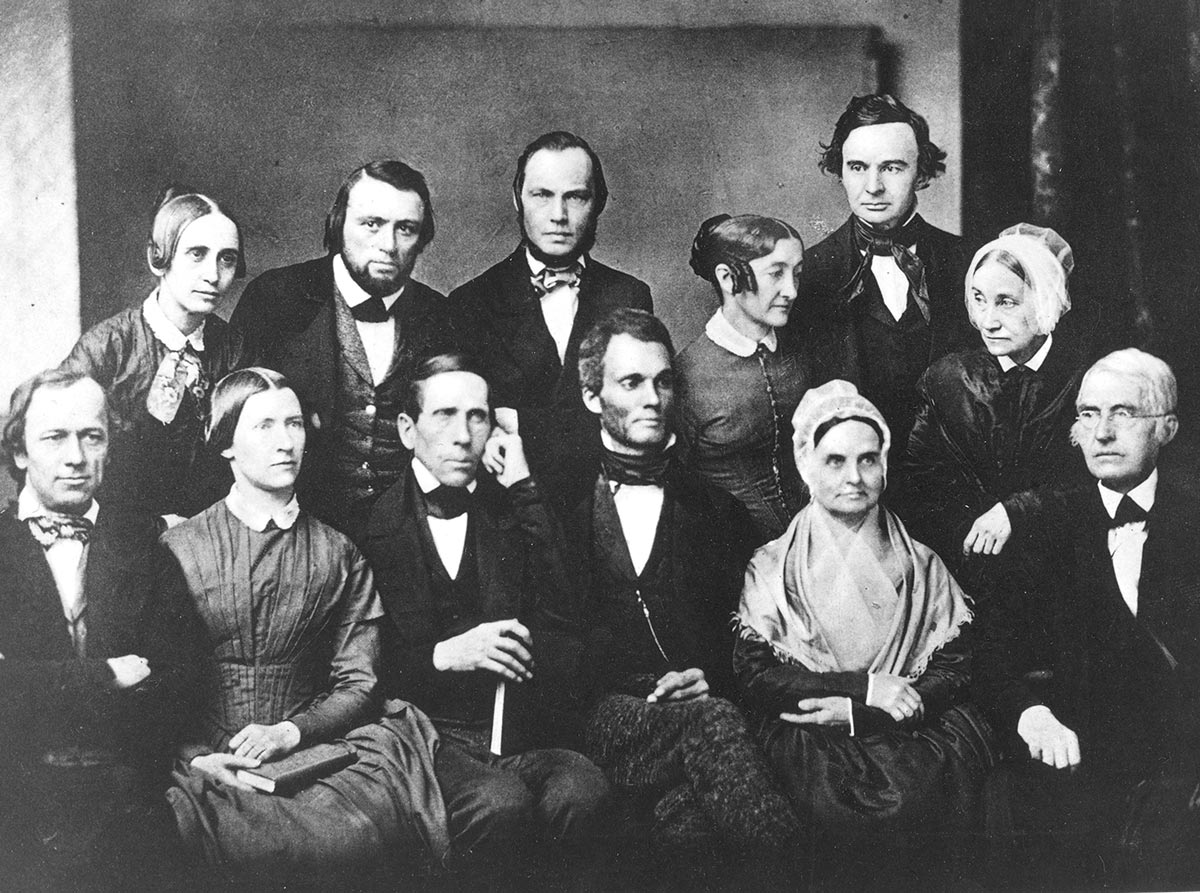

courtesy of Friends historical library

Firebrand

Lucretia Coffin Mott spoke across the divide and against social injustice. Her words are more timely now than ever.

by Jamie Stiehm ’82

“She spoke to the world through every line of her countenance … bearing a message of light and love.”

—Frederick Douglass

ucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880) is one of the best-kept secrets in American history — and even at Swarthmore, where she was a College founder as the Civil War raged.

I fell under her gaze in a Parrish Parlor portrait now in the Friends Historical Library (FHL). Her fine eyes were set off by a Quaker sheer cap and fichu, a woven shawl. I felt she was speaking straight to me. Her fame, after all, was as a public speaker with magnetic moral charisma that helped expand American democracy.

“Woman has long been excluded from the privilege of speaking to the people.”

—Lucretia Coffin Mott, 1843 address to members of Congress.

courtesy of Friends historical library

Firebrand

Lucretia Coffin Mott spoke across the divide and against social injustice. Her words are more timely now than ever.

by Jamie Stiehm ’82

“She spoke to the world through every line of her countenance … bearing a message of light and love.”

—Frederick Douglass

ucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880) is one of the best-kept secrets in American history — and even at Swarthmore, where she was a College founder as the Civil War raged.

I fell under her gaze in a Parrish Parlor portrait now in the Friends Historical Library (FHL). Her fine eyes were set off by a Quaker sheer cap and fichu, a woven shawl. I felt she was speaking straight to me. Her fame, after all, was as a public speaker with magnetic moral charisma that helped expand American democracy.

But this Philadelphia Quaker did not write for the future. She acted in the present, out and about all over America, breaking silences and rules in the public square.

In 1838, Mott was targeted by a mob of young Southern pro-slavery men who had just burned down Pennsylvania Hall, newly built by the city’s anti-slavery society.

They were outraged that Mott encouraged Black and white members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society to walk together. At home, Mott waited for the mob at midnight, but poet John Greenleaf Whittier pointed it the wrong way. The parallels with our violent era are plain.

As one who was huddled in the Capitol on Jan. 6 under siege, I can bear witness to that.

Mott was one of the first Americans to hold integrated political gatherings in her large family home, which became a beacon and shelter for travelers between Washington and Boston. Her dining room seated 50 people, all comers of all kinds, from the Rev. Samuel J. May (Louisa May Alcott’s uncle) to an enslaved Virginia man who mailed himself in a wooden box to the Philadelphia anti-slavery office. Henry “Box” Brown came to tell her of his journey to freedom. The venerable Sojourner Truth was a guest. So was Mary Brown while her husband John was being hanged for leading a slave revolt in Harpers Ferry, Va.

The reviled 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and the Supreme Court’s infamous 1857 Dred Scott ruling — which held Black people could never be citizens — were surely among table topics.

In short, “Mrs. Mott” knew everyone and everyone knew her as a leader in the world of dissenters and reformers.

By Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln caught up to the radical revolution that Mott, Garrison, and others championed — freeing four million enslaved people by his hand. Mott was almost 70 on the joyous day of the Emancipation Proclamation (which left slavery intact in four border states). She had held one of the first high teas for the American Anti-Slavery Society back when she was 40.

As a birthright Quaker girl on Nantucket Island, where the Society of Friends was the predominant culture, the confident, bright Lucretia Coffin was a first-class citizen. It helps to explain her extraordinary upbringing to know that the Friends were among the most egalitarian religions and the first American faith to oppose slavery.

Her father Thomas was a sea captain. Most Nantucket men (and boys) were seafarers who sailed for long voyages, leaving self-reliant women (and girls) to run daily life. Lucretia’s island sensibility — seeing society at a distance — stayed with her. Yet she was born in the first post-Revolutionary generation, eager to shape democracy in the right direction.

When she was a young mother in Philadelphia, married to James Mott, Lucretia’s Friends meeting realized she was a speaker of rare distinction. It’s no accident she flowered in that garden. Friends were among the few with a format that empowered women to speak in worship. Society at large enforced strict domesticity for women in a “separate sphere.” Mott took the Quaker “Inner Light” spontaneous manner of speaking — as the spirit moved, with no notes — out to the wider world. But many of her words in preserved speeches still resonate on the page, says Mott expert Beverly Wilson Palmer, editor of her letters. However, her chatty letters do not capture her greatness. In 1840, Mott made a splash in London at the World Anti-Slavery Convention. As an American delegate, she was shut out because she was a woman. She soon became a cause célèbre, “the Lioness of London,” invited to speak around the British Isles. Impressed, Charles Dickens called on her in 1842 when he passed through Philadelphia. Mott’s London diary is on loan from the Friends Historic Library to the National Constitution Center. In 1843, congressman and former President John Quincy Adams invited her to address Southern congressmen on the “sectional divide,” as the increasingly contentious fight over slavery was dubbed. Evoking the prophet Isaiah, Mott held a hushed, full church in her hands, speaking across that divide for one winter night, which made the Washington newspapers. She was 50.

courtesy of Friends historical library

“Mott saw the sisterhood of different reforms,” says FHL Archivist Celia Caust-Ellenbogen ’09, noting peace was another cause. Most of her letters and mementos are in the FHL, which is the “epicenter” for historians researching Mott, says Caust-Ellenbogen.

Mott is right on time for us and far ahead of hers. One of several organizers of women rights at Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848, Mott is cast in stone in the Capitol Rotunda, with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, younger women she mentored. She lived to see emancipation succeed, but not suffrage. And if only that stone could speak: “I long for the day my sisters will rise.” The Quaker’s great gift was her radiant voice, which mesmerized and moved multitudes.

Abolitionist orator Douglass and Concord sage Ralph Waldo Emerson recorded their amazement at witnessing Mott. According to one writer, her thoughts “pour upon her like a summer flood.”

Imagine that.

Jamie Stiehm ’82, a Washington columnist, is a public speaker on American history.