common good

shedding light

Degrees of Separation

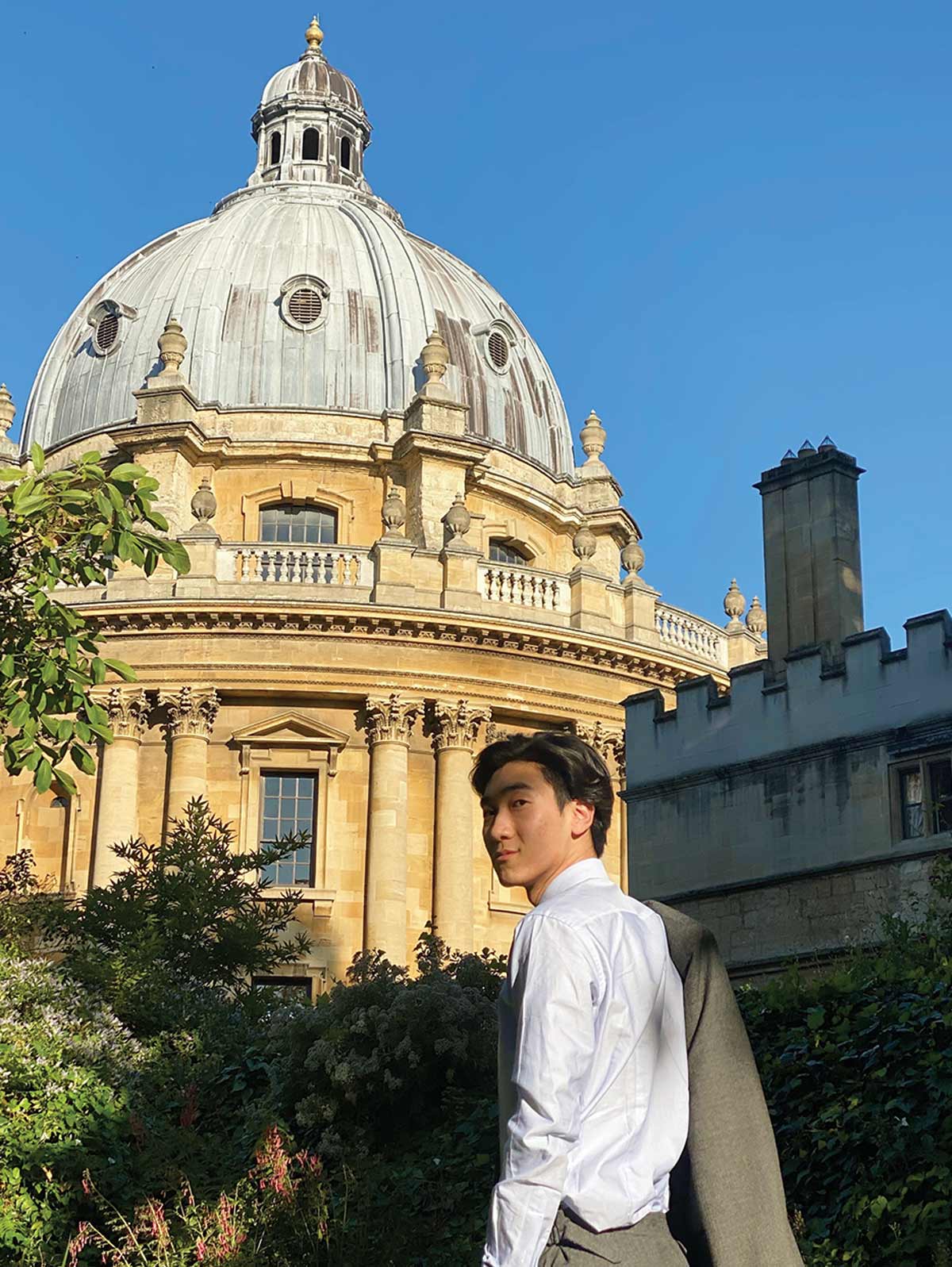

IN WHAT SENSE CAN international students go home again? Yifan Ping ’21 is combining intellectual curiosity and compassion with ethnographic methods to shed new light on the personal and global impacts of educational migration.

“Every day I spend with my interlocutors, new data emerges and shapes my research,” says the University of Oxford Weidenfeld-Hoffmann Scholar. Ping, who uses the pronoun they, graduated from Swarthmore with a major in sociology & anthropology and minors in educational studies and Japanese.

Ping has spent the past year digging deeper into questions they first formulated for their Swarthmore senior thesis, which examined the experiences of high-achieving middle-class Chinese students studying for the GRE in the U.S. Many of them, Ping found, saw little value in American educational practices.

Degrees of Separation

IN WHAT SENSE CAN international students go home again? Yifan Ping ’21 is combining intellectual curiosity and compassion with ethnographic methods to shed new light on the personal and global impacts of educational migration.

“Every day I spend with my interlocutors, new data emerges and shapes my research,” says the University of Oxford Weidenfeld-Hoffmann Scholar. Ping, who uses the pronoun they, graduated from Swarthmore with a major in sociology & anthropology and minors in educational studies and Japanese.

Ping has spent the past year digging deeper into questions they first formulated for their Swarthmore senior thesis, which examined the experiences of high-achieving middle-class Chinese students studying for the GRE in the U.S. Many of them, Ping found, saw little value in American educational practices.

When Ping traveled back to China after graduation last summer, they met multiple Chinese international students who were disenchanted with the U.S. and enamored with China.

“So I was curious,” says Ping. “How do these young diasporas who spent years in the U.S. return to their ‘unfamiliar’ motherland? Why do they still ‘love their country’?”

Ping’s own educational journey, leaving Nanjing to study at Miami Valley School in Ohio before attending Swarthmore, gives them a kind of embodied access to examining these complex questions. The research involves not only interviews but also observing and participating in lived experience through fieldwork.

“I pay attention to how someone goes about their daily life in the U.S. as a resident alien, racial minority, and socio-economic elite,” Ping says. The resulting interpretive description can illuminate the culture in which these behaviors are observed.

The extent to which many Chinese students are consciously resisting and deconstructing Chinese nationalist narratives and myths even as they express love of their country surprised Ping. They’ve observed an interesting interplay between ideological patriotism and material patriotism. “Patriotic sentiment is not only about national propaganda and political narratives. It’s also about lived experiences and bodily feelings grounded in a particular place,” they say. The national pride and patriotism these immigrants feel is not completely abstract, Ping says — in part because they have vivid memories of life in China that contrast sharply with their lives in the U.S.

Ping hopes these insights will shape how people view Chinese students in the U.S. — not as submissive political objects under an authoritarian communist regime, but as critical subjects whose creative agency can and does shape their own ideologies and approaches to national identity. And, Ping adds, “do not assume they are not able to talk politics just because they are Chinese international students.”

Ping’s work will take them next to UNESCO headquarters in Paris to continue their internship as a research assistant. While Oxford has offered Ping great opportunities to grow professionally and interact with world-class scholars, they have missed the sense of family and heartfelt interpersonal exchanges they enjoyed at Swarthmore. “Swarthmore really is a big family,” they say.